[Be sure to click through all the images in the gallery above.]

The surface was alive with thousands of tiny worms darting under the lights in erratic circles. Stripers rolled on the surface as far as I could see. I’d stumbled upon something epic: a hatch of cinder worms, perhaps the most fascinating, mysterious and simultaneously frustrating phenomena in Northeast saltwater fishing. Not only are the stripers that feed on them incredibly hard to fool, the hatch itself is elusive.

When it goes off though, it might be the ultimate experience in Northeast light-tackle fishing. It is the only time when conquering a 40-plus-inch striper with a 1-inch bait is a possibility.

Cinder Worm?

Cinder worms are a polychaete (many legs) in the Nereis genus, which also includes the more-familiar sand worm (Nereis virens) and the common clam worm (Nereis succinea).

There are hundreds of species of Nereis worms. What we call cinder worms (Nereis limbata) are generally one to three inches long with an off-color — usually olive — head and a pinkish body. But their size, shape and color vary, not only in different regions, but from salt pond to salt pond. Cinder worms are fairly immobile, so at each location, they have evolved differently, and hatch under varying conditions.

Hatch or Spawn?

Like all Nereis worms, cinder worms are mud burrowers. When conditions are right, worms develop a tail paddle, releasing all but the segment of their body containing the reproductive cells. They swarm to the surface, releasing their sperm and eggs in a frenzy. The adults then die, and fertilized eggs drop to the bottom.

Technically not a hatch but a spawning phenomena, the moniker has stuck nonetheless, for obvious reasons, as the sudden emergence of the worms closely resembles a hatch of aquatic insects.

Timing

While their range is uncertain, anecdotal information suggests significant cinder-worm hatches from the Chesapeake Bay to Maine, with the bulk of the activity in New York, Connecticut, Rhode Island and Massachusetts.

Hatches are a spring event in most places, occurring in the dead of night, with some exceptions in Rhode Island and Martha’s Vineyard, where they can occur in late afternoon.

The consensus is that hatches happen from May to early July. Yet, in one of the few studies on Nereis limbata, Frank Lillie found swarms in Woods Hole from June to September.

Cinder worms spend most of their lives in the mud, thus hatches usually occur in salt marshes. Lighted areas definitely attract hatches. Lillie found during his study that cinder worms moved toward the light of his lantern.

Long Island guide Paul Dixon looks for tidal outlets, noting that the strong currents are what start the hatch. “It’s a survival technique to distribute the fertilized eggs,” he reasons. The current carries the emerging worms, and striped bass set up in spots stemming the tide to pick off the worms.

Variables

Conditions have to be perfect for a full-blown hatch, thus they have a reputation as elusive because the variables often don’t line up. “Worm hatches are a local phenomenon and quite variable,” says Alan Caolo, author of Sight-Fishing for Striped Bass. “Which explains why so many hypotheses are correct and at the same time contradictory.”

Still, there are some constants that, combined with local knowledge, enable predicting the hatch in particular areas.

There’s evidence that cinder-worm hatches are brought on by moon phase. “The occurrence of swarming is dependent more on lunar cycle than any other factor,” notes Lillie. “Each run begins near the time of the full moon, increases to a maximum during successive nights, sinks to a low point about the time of the third quarter, and then again rises and falls to extinction shortly after the new moon.”

Caolo argues that hatches are determined by temperature in the sediment and the water column. New and full moons increase tidal highs and lows. Cinder-worm emergence might be stimulated by the sun warming bottom sediments during lower-than-average tides. Yet it still takes a certain temperature in the water column as well for the spawn to go off. “If you have a day with high sun and low water because of the full-moon phase, [the hatch] may go two days strong, then if it gets cold and gray, it will turn off right away,” says Caolo. “Just about everything that is cold-blooded is really a function of temperature.”

Two studies in the journal Marine Biology confirm Caolo’s theory. In 1988, O.F. Müller exposed Nereis worms to different temperatures and found spawning was induced by raising the temperature. In 1987, Heinrich Frey and Rudolf Leuckart conducted a similar experiment. Spawning was induced by raising temperatures around the time of the new moon. Lunar periodicity was illustrated under natural temperature programs, but it also demonstrated that an abrupt increase in temperature caused swarming to occur at different times of the lunar cycle.

You probably won’t find a hatch under windy conditions. “When a female appears, she’s soon surrounded by several males, which swim rapidly in narrow circles around her on the surface,” notes Lillie. Worms indeed might emerge from the mud during windy conditions, but they likely can’t perform such mating behavior if there are waves tossing them.

Current Considerations

Fishing a hatch is difficult without moving water. You might see stripers slurping worms all over the place, yet because the amount of bait is extraordinary, getting your offering noticed isn’t easy. In such situations, fish will cruise to the worms. This means you have to anticipate their movement.

It gets easier with current. “Worms are fairly immobile in the face of even moderate flow,” notes Martha’s Vineyard guide Tom Rapone. “Stripers line up at feeding stations to take advantage of the easy meal sweeping by. Stripers holding in a current seem more likely to single out individual targets.”

Match the Hatch

“Fishing the hatch on the days leading up to the peak or in the days where it begins to wane can be better, as there are fewer real worms,” notes Dixon. On such nonpeak days, matching the hatch is a good bet. When the hatch is in full swing and there are thousands of worms in a small area, a different approach is required. “There’s often so much bait in the water, just throwing something bigger will induce strikes,” says Blinken. Caolo likes soft plastics: “Four-inch pink Slug-Gos are about as deadly as you can get.”

Presentation

Caolo likes a floating fly line and a 7- or 8-weight fly rod. He recommends keeping the fly near the surface, making small erratic strips and then allowing it to drop for a few seconds. Dixon recommends dead-drifting the fly with a floating line while mending it, keeping just enough tension to feel the strike. With spin gear, slow it down. Fish do not put out more energy than they need to in acquiring prey.

Cinder Worms Tackle Box

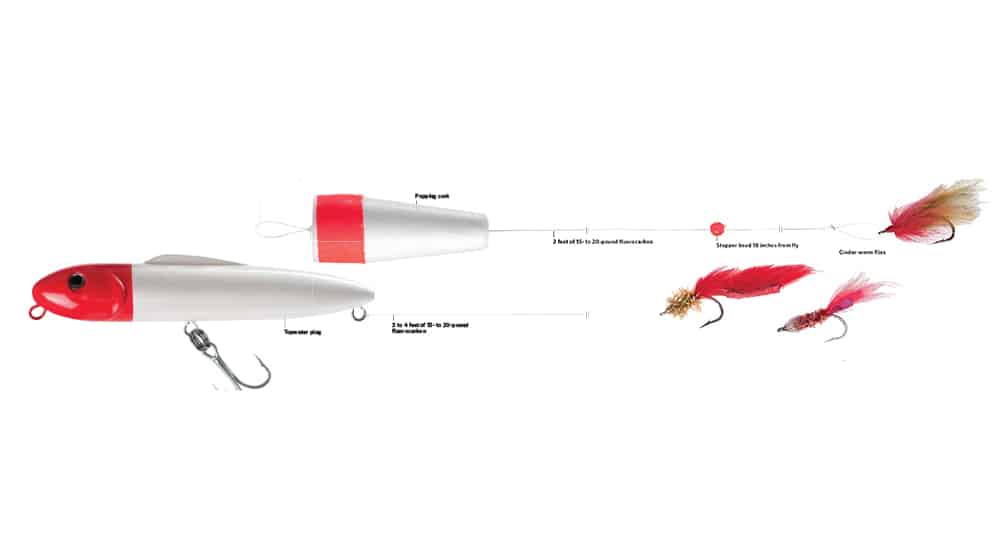

Fly-fishers have an advantage in a cinder-worm hatch because it’s difficult to match such a small bait with lures made for spinning tackle. Still, spin-fishers adapt by tying a cinder-worm fly a couple of feet behind a plug, then working it slowly. Some anglers employ a float and a cinder-worm fly two or three feet below it.

Regarding fly selection, cinder worms are in the red spectrum ranging from an orange-brown to reddish pink, so matching the color and size is a good place to start. I use a simple fly, a 1-inch red Zonker strip and an olive Ice-Chenille head tied on a 1/0 hook.

Rods: 7-foot medium- to light-action spinning rods, 9-foot, 7- or 8-weight fly rods

Reels: Smaller saltwater reels with smooth drags, such as Van Staal VS100 or equivalent

Lines: 15- to 20-pound braid, weight-forward floating lines for fly-fishing

Leader: 4 feet of 15-pound to 20-pound-test fluorocarbon, 8- or 9-foot tapered leader with fluorocarbon tippet for fly-fishing

Lures/Terminal Gear: Topwater plug with a 3- to 4-foot fluorocarbon trailing leader and cinder-worm fly, or a snapper-float and a cinder-worm fly two or three feet below it.

Cinder Worms Planner

What: Striped bass and weakfish

When: May and June

Where: New York, Connecticut, Rhode Island and Massachusetts estuaries

**Who: **

Martha’s Vineyard, Tom Rapone, www.highlymigratoryfishing.com

Rhode Island, Robert Hines, www.flyfishri.com

Connecticut, Ian Scott Devlin, www.devlinfishing.com

Eastern Long Island, Paul Dixon, www.northflats.com

Western Long Island, John McMurray, www.nycflyfishing.com