Scientists know a lot more about marlin, sailfish, and spearfish than they used to, thanks to tournament anglers who go to the trouble and expense of tagging and releasing billfish. By participating in the IGFA Great Marlin Race, established in 2009, these anglers have taught the world a great deal about where and how these magnificent fish live.

It’s no small commitment; individual anglers or their teams foot the $4,000 bill for the satellite tags. But these people are accustomed to going all-in for their sport.

Committed Anglers and Conservationists

“Recreational anglers are sponsoring the tags and deploying the tags, and they’re obviously a crucial element of this,” said Bruce Pohlot, Ph.D., conservation director for the International Game Fish Association. “These are people that are heavily involved in the tournament world and the billfishing community. There are people out there that are so interested in these fish and the future of this fishery that they’re willing to lend support in this way. It’s the cornerstone of program.”

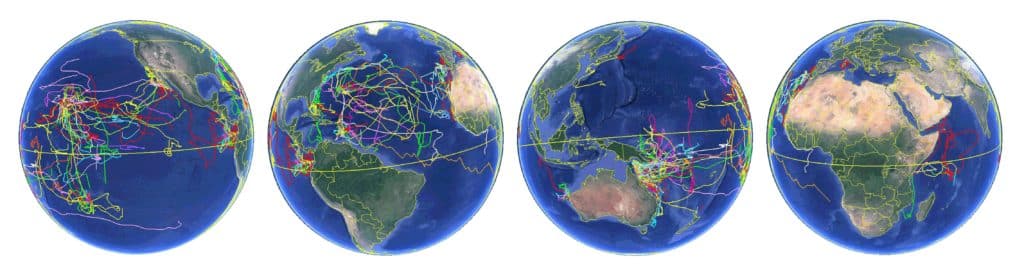

That includes people like Tony Huerta, owner of the 58-foot Lo Que Sea out of Fort Pierce, Florida. Huerta sponsored the tag on a 300-pound blue marlin, caught by angler Andrew Brady, that won the race last year. From the time when the fish was caught, during the 2021 Big Rock Blue Marlin Tournament in North Carolina, until its tagged popped off and began transmitting data 240 days later, it swam nearly 8,000 nautical miles.

That’s how the “race” works: the fish that travels farthest from where it was tagged is the winner. Huerta’s marlin zig-zagged around a bit off the New England continental shelf, then swam clear across the Atlantic, south along the coast of Africa, and back west, losing its tag 800 miles east of French Guiana.

The program began as a partnership between the Hawaiian International Billfish Tournament and Dr. Barbara Block of Stanford University in 2009. The IGFA came on board in 2011 and expanded the event to tournaments (and non-tournament tagging) around the world. Today, the race is sponsored by Costa Sunglasses, AFTCO, Bass Pro Shops and Cabela’s Outdoor Fund, EdgeWater Boats and Release Boatworks.

Important Fishery Science

What can be learned from knowing where a fish has traveled? Enough for eight peer-reviewed studies and counting. Tagging shortbill spearfish for the first time ever revealed the species dives to hunt overnight and hangs closer to the surface during the day—exactly the opposite of most billfish, which hunt by day and hold near the surface at night. Another study, done by Pohlot while earning his doctorate at the University of Miami with Dr. Nelson Ehrhardt, examined how daylight (or even a full moon) affects the activity of sailfish in the eastern Pacific.

Nineteen tags were deployed in the 2021-2022 race, providing info on 17,471 nautical miles worth of travel. We know that Huerta’s marlin, for example, at one point dove nearly 1,500 feet.

Knowing where billfish go provides important data for conservation and regulation. There’s no commercial fishery for billfish, but they often end up as bycatch in the tuna and swordfish fisheries–sometimes reported to regulatory agencies, sometimes not. Knowing that marlin or sailfish are in a particular jurisdiction can help governments write enforceable rules. Great Marlin Race data were used in writing the 2012 Billfish Conservation Act, which outlawed the importation of billfish to the U.S.

More Participation on Deck

“(Billfish) are managed, but we’re still missing a lot of information about them,” Pohlot said.

The 2021-22 race included the Big Rock, Custom Shootout (Abaco, Bahamas), White Marlin Open (Ocean City, Maryland), White Marlin Invitational (Beach Haven, New Jersey), Mobile Big Game Fishing Club Labor Day Invitational (Orange Beach, Alabama), Master Angler Billfish Tournament (Southern California), and the Bermuda Triple Crown.

“In 2023 we will be adding more tournaments to the list, and we also have other events not affiliated with tournaments,” Pohlot said. “In fact, many of our tagging events are among private fishing clubs or part of grants we get.”

Another advancement for the race would be tags that stay with the fish longer before popping off. Pohlot wondered where Tony Huerta’s marlin ended up after a full year.

“If we had had the full 365 days, I would have loved to see if the fish went back to North Carolina, or if the fish would go to the Dominican Republic or the Bahamas,” he said. “We just don’t know.”