Click through all the images above to see photos from the trip to Turneffe.

“Ernest Hemingway once said, “The best way to find out if you can trust somebody is to trust them.” I think what Papa meant by that was, when it comes to putting your confidence in something, people simply have to take leaps of faith. When something feels right inside, trust your gut and you can’t go wrong. Case in point: Craig Hayes. Hayes fell for the beauty, bounty and culture upon his first steps on Belizian soil in1977. After several trips, he finally made it to the Turneffe Atoll and it was love at first sight. There was just something about the island that called to him. Instead of dipping his toe in to test the waters, self-assured, he practically decided right then and there to jump in the deep end and start a bonefish lodge. Who would have thought that, after 36 years, the bonefish camp that began as nothing more than a dock and an outhouse would turn into Turneffe Flats — a high-end lodge located smack-dab in the middle of one of the world’s most diverse and precious marine ecosystems and home to one of the finest bonefish, permit and tarpon fisheries an angler could ask for.

Just as it is for Hayes, Belize will always occupy a special place in my heart. The first time I traveled to the former British Honduras was in 2002, and it was during that monthlong trip that I landed my first bonefish and exposed my fly-fishing taste buds to the flavor of exotic travel. The first three weeks of this trip were spent on the interior of the country, which quickly made me realize that there’s much more to this small country than fishing alone. While I didn’t make it to Turneffe, I did spend a week on Glover’s Reef, which sits roughly 25 miles south. The guides spoke of Turneffe often. They compared stories about the Coolly Lady, the ghost that haunts the island; the ecosystem; the remoteness — they even swore up and down that Turneffe has golden bonefish that always lead the school. When they talked about the island, they lit up as if it were the Garden of Eden.

Ever since then, the atoll has had a mysterious draw to it. In August 2012, after years of waiting, I finally found myself on a dive boat leaving the port in Belize City with a heading pointed at Turneffe. I couldn’t wait to see if the hype I’d heard so long ago was accurate.

As on my initial trip to Belize, I spent hours at the vise, and I compared my patterns with photographer/fishing guide Scott Sommerlatte’s, who’d be joining me. Prior to our departure, Sommerlatte and I developed a game plan. We figured we’d spend the first day catching as many bonefish as possible and then spend the rest of our time on the water hunting for permit and tarpon. As with any well-thought-out plan, things didn’t happen that way.

Our Belizian guide, Dion Young, adopted our strategy, and in no time flat he spotted one of the largest schools of tailing bonefish I had ever seen. The three of us made a stealthy approach and figured it was only a matter of minutes before our rods were bent and our drags were screaming. Right before we were in casting range, we saw exactly why these bones were swimming in inches of water. A huge barracuda was sitting stationary in the deeper water adjacent to the flat waiting for a bold fish to leave the group.

We made a couple of casts into the mix and didn’t get as much as a follow. While Sommerlatte and I both realized that we could beat these fish to death and probably hook up, Dion suggested we move on. He felt that a ’cuda of that size waiting in the wings meant certain death to a struggling bonefish. We agreed, but instead of moving on, the three of us just stood there and watched. For Sommerlatte, it was a prime opportunity to fill a memory card with epic photography, but for me, it was an hourlong reminder of exactly why I love to fly-fish. It also served as one of many visuals I’d see in the days to come of what makes Turneffe such an amazing resource. I don’t know if it was the giant ’cuda hanging out only yards away or whether it was the fact that the fish got used to our presence. Whatever it was, they stayed put, allowing us to enjoy the moment. When we did decide to move, Young indeed put us on more willing bones, but it was that school that we watched that I will remember the most about that day.

By the time we’d returned to the lodge and set our wading boots out to dry, Hayes, owner of Turneffe Flats Lodge, had just arrived back at the island after a short business trip. At dinner we chatted with Hayes about many topics, including how to grow the sport of fly-fishing, the best permit flies and whether or not the wind would lie down the next day. This would be the pattern each night, but one subject that almost all of our discussions circled back to was the conservation issues Turneffe faced. It was obvious these issues were very important to Hayes, and while he’s a self-proclaimed naturalist and a devout conservationist, I believe the reason why it’s such a big deal to him is because, just like it did to me, Hayes’ first trip to Belize changed him. So much so, it eventually inspired him to start the Turneffe Atoll Trust in 2002. The trust is a nonprofit organization that follows a simple mission: to promote conservation that benefits a healthy ecosystem while stimulating social and economic benefits for the country of Belize. With any luck, the trust will continue to thrive and can serve as a model for other threatened, valuable, unique and diverse marine ecosystems.

Over the next few days, Sommerlatte and I found our fill of happy bonefish, scratched our itch for a catch-and-release frenzy and decided it was time to up the challenge and target permit, the fish that I call my white whale. I’ve done everything right so many times, and up until this point the only things I’ve had to show for my efforts have been a few stories about a fish or two that followed the fly. As he had been each preceding morning, Dion was happy to accommodate, but he was also realistic.

He informed us that the schools of permit that he’d been seeing had mooning fish (fish swimming on their side close to the surface) among them. He said this was an indication that the spawn was on. Clearly, if this was in fact the case, the permit in these schools would likely have other things on their mind than eating. But it’s difficult to know a school of permit would be easy enough to find and not at the very least give it a try.

Skies were gray with intermittent bursts of sunlight, but even then visibility was minimal. Each permit search seemed as though we were beating a dead horse; however, inevitably Dion’s voice would break the silence and desperation by saying, “Ahhh, there they are.”

After we’d made cast after cast to I don’t know how many schools, Sommerlatte’s line came tight after a long, slow strip followed by a drop. His line sprang from the deck into a controlled aerial tangle before it was securely on the reel. After the first blistering run, Sommerlatte reeled with abandon to regain his line, but the permit had other plans and bolted away from the skiff for a second sprint. When we got the permit to the boat, I congratulated him — and why wouldn’t I have? He’d accomplished a great angling feat. OK, so I was slightly bitter. We had essentially been doing the same thing for a couple of days at that point. I just couldn’t figure out what he did that I didn’t. Even though our days were numbered and our time on the water was dwindling away, I trusted that something good would come my way — there was something in the air that told my gut that my time would come.

Each night, our conversations with Hayes continued, and with each day on the water, I realized that my focus was waning from catching a permit and becoming more about soaking in the experience and enjoying what a rare and beautiful ecosystem Turneffe truly is.

On the morning of our last fishing day, I woke up permitless but content nonetheless. We set out, had a shot at a permit here and there, and caught a few bones. As the sun began to fall, Dion asked, “You guys had enough or do you want to hit one last flat before the sun goes down?” Sommerlatte and I looked at each other and both agreed to keep the boots on for one last session.

“Just bonefish on this flat?” I asked Dion. “Yeah, every once in a while you’ll see a permit but not very often,” he replied. I tied on a No. 8 bonefish bitter that had been the winning pattern for the bonefish we’d caught and stepped out of the skiff into the soft marl. I took two steps and stopped. I looked out across the white sandy flat in front of me and had a sudden change of mind. I snipped off the bitter and tied on a small crab fly, just in case.

About the time I cinched my knot, I heard Dion’s voice say, “Look! You see the gold one?” Even though the idea of a golden bonefish specific to Turneffe added to its allure, when I’d heard about it, I’d never believed it. But when I looked up and allowed my eyes to follow Dion’s finger, I couldn’t help but say in disbelief, “I’ll be damned!” Just as it was described to me, a single bonefish that looked as though its maker had colored it with a yellow highlighter was leading the school. As with the group of bones we saw the first day, we didn’t get an eat out of this one, but once again, that goldish-color fish will be tattooed in my brain forever.

After a little more wading, we all went our separate ways, and out of nowhere, I spotted several small fish with black tails nervously darting across the flat. Sure enough, they were permit. They were so frisky it was impossible to get a beat on them. So basically, I had to roll the dice and choose one direction to walk in order to flank them. All I could do at that point was hope their internal compass would cooperate with my position. I took a leap of faith that tipped the scale in my favor. The three permit simultaneously made a hairpin turn to the right, which gave me a perfect 11 o’clock shot at the lead fish. When the fly dropped, all three fish charged with a vengeance. It was at that moment I knew one of them was going to eat. I stripped long and slow and kept the fly only inches out of reach. As soon as I stopped and let the fly drop, I saw the black tail of the leader of the pack break the surface and felt weight behind my next strip. I think I caught the world’s smallest permit. But, nonetheless, it was a permit and could very well be the most memorable one I’ll ever catch.

Just like I felt deep down that my decision to head right on that small group of tiny permit was right, and just like Hayes’ faith in his business instincts paid off, I firmly believe that, as the Turneffe Atoll Trust plan continues to develop, the resource will remain and will likely become even more pristine than it already is. I trust that, with this plan in place, my children’s children can enjoy the same beauty, uniqueness and outstanding fishing that I have.

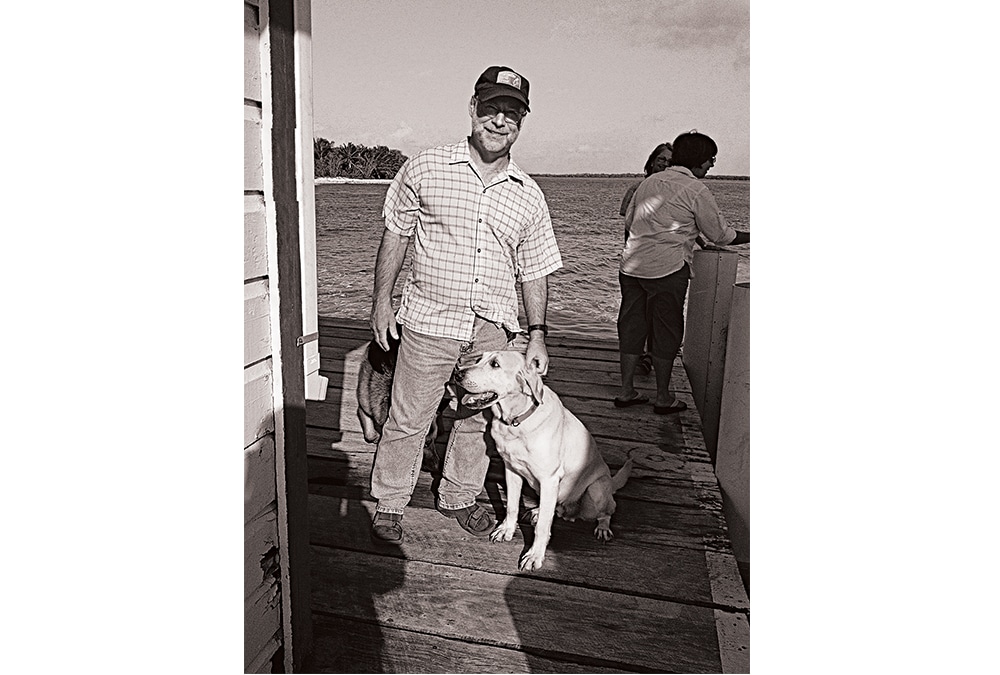

Man with a Vision

In 1977 Craig Hayes traveled to Belize on a whim. After many return trips over the period of a few years, he decided that it would be fun to run some kind of business there. While he never set out to create a bonefish lodge, an article he read in Sports Illustrated about bonefishing on Turneffe sparked the idea. Turneffe Flats may have had a very meager, very rough start, but over the years it has developed into a rather posh lodge, an accomplishment Hayes credits to making every mistake at least twice.

When he’s not overseeing the day-to-day operations of the lodge, he’s working on his other passion, which, wouldn’t you know, is based on Belize: the Turneffe Atoll Trust.

As the lodge developed, Hayes began thinking about doing more to preserve the atoll. While Hayes was making his plans, Craig Mathews, founder of Blue Ribbon Flies, and Yvon Chouinard, founder of Patagonia, started 1% for the Planet. Liking the idea of taking a percentage of sales and putting it toward the environment, Hayes felt the concept was perfect. To facilitate this, he founded the Turneffe Atoll Trust, so now his donation through 1% primarily goes toward conservation measures right in his Belizian backyard. The trust’s biggest effort in years past has been instituting a law that completely protects bonefish, permit and tarpon in Belize. This is an effort that has been extremely successful and is even being emulated by other countries. More recently the trust’s main objective has been to establish the Turneffe Atoll as Belize’s largest marine reserve. The five-year management plan that the Turneffe Atoll Trust funded and helped to develop included a declaration that would officially make this so, and it was passed on Nov. 22, 2012.

Booking ****Your Trip

If you would like to find out even more information about how you can arrange your own trip to one of the Caribbean’s most diverse resources, contact the booking agencies listed below:

Frontiers Travel: www.frontierstravel.com

Yellow Dog Flyfishing: www.****yellowdogflyfishing.com

Angler Adventures: www.****angleradventures.com

Angling Expeditions: www.****anglingexpeditions.com