The Automatic Identification System receiver on tournament pro Capt. George Mitchell’s Snake Dancer came at his sponsor Furuno’s request for a temporary installation of the FA30 for boat-show demos. But after that he wouldn’t give it back. “I won’t fish without it,” says Mitchell.

So how does a device designed to track freighter and commercial traffic benefit recreational fishermen? Anglers need three things after they are tackled up: skill, luck and information – and in many cases, good information makes up for a lack of the other two.

AIS allows Mitchell access to a large reservoir of information. For tournament anglers hitting unfamiliar waters with a hope of finishing in the money or for weekenders hoping to leave the office on Friday and fill the fish box before Sunday night, AIS can open wide that limited window of opportunity.

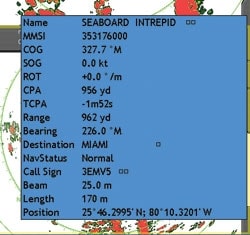

Here’s how it works: AIS picks up a VHF signal from a ship’s transmitter and displays, on the receiving boat’s plotter screen, an icon and a data panel showing, among other things, the transmitting ship’s name, size, course, speed and Maritime Mobile Service Identity number, which is its “phone number” on VHF and allows anyone to call it directly. While it may not do an angler any good to know the M/VFree Spool sailing under the flag of Singapore, is carrying a load of coal to Newcastle at 12 knots, that information does offer inroads to valuable information.

Get Connected

“The MMSI number and name allow you to call a vessel directly and address it by name. That gives you instant credibility,” says Mitchell. “If you get on the radio and say, ‘Anyone in the anchorage?’ no one is going to answer you. If I say, ‘Freighter Magic Fingers, this is recreational boat Snake Dancer approaching on the starboard bow; we’d like to catch bait off your anchor chain,’ they’ll talk to me.”

Once you have properly opened the lines of communication, the information begins to flow. For instance, you can find out how long they have been at anchor, which can be useful. “Let’s say I’m in Port Everglades, [Florida,]” says Mitchell. “If they have been anchored there for two days, I know I’ll find blue runners under the ship. After three days, I’ve got goggle-eyes early in the morning. After five days, I’m thinking cobia, king mackerel and a lot of other stuff.”

You can coordinate this information with your seasonal knowledge, Mitchell says: “On the full moon in August in Port Everglades, I know if I find goggle-eyes on a ship, I can catch them, cut them in half and drop them back down on the bottom, and I’ll be getting big mangrove snapper.”

On the Move

AIS is also helpful dynamically, such as when you’re dealing with the Gulf Stream, Mitchell explains. “I’ll look at the freighter icons with the arrow pointing in their direction of travel,” he says. “If they are southbound and in tight to the reef line to save fuel, I know before I even get there that I’ll find a lot of current and a blue-water edge. If they are in the middle heading south, I know there is not a lot of current today, and I can fine-tune my fishing or travel plan.”

Speaking with those vessels, Mitchell says, yields information about current, set and drift, valuable when crossing the Stream. And sometimes there’s more, “One day I talked to a guy coming out of Great Isaac, in the Bahamas, told him where I was headed, and he happened to mention, ‘You should see the boats off Walker’s Cay; there are weeds and porpoises, and everybody is catching tuna.'”

Thick of It

In the Gulf of Mexico, constant activity in and around the oil fields yields plenty of actionable information. “I check with the tenders that travel to the platforms,” says Mitchell. “They will tell you where they are going and where they will anchor, which gives you a good idea of the current around the platform.”

This, in combination with an ocean-reporting or sea surface-temperature overlay, begins to paint a telling picture of offshore conditions.

Mitchell says tenders can provide information about obstructions or dive operations in the area, which would preclude fishing around those platforms. Conversing with the tenders and the platforms allows him to find out what’s going on and exercise courtesy that often elicits even more information.

“I may explain we are planning on flying a kite and ask them to let us know if they have incoming helicopters so we don’t interfere with those, which they appreciate,” he says. In return, maybe they offer additional information, such as the movement of a drilling ship, which acts like a giant fish haven. Often the crew boats explain they are just making a delivery, which is also good news.

“Once they arrive and push ‘Stay’ on their GPS and autopilot, which holds them in position to unload, the white water starts to flow around the tender and the platform, and that reshuffles the deck,” Mitchell says. “The white water blows the bait off the platform, the ‘cudas go wild on the bait, the wahoo go wild on the ‘cuda, and the blue marlin eat the wahoo. It’s like an alarm clock going off if there are fish there.”

The crew that lives on the water gathers information that anglers cannot get without spending day and night at sea themselves. Tapping into that information can be like opening a library dedicated to your fishing. Properly and courteously used, AIS can be your library card.