A brassy orange flag sporting a black spot poked through the glassy surface of the Neuse River in North Carolina, and I chucked a bunker chunk on a slide rig 10 feet from the waving tail.A little tap was followed by a vibration on the line and then a slow, steady pull. The 25-pound red had taken the bait, and I locked the reel in gear and let the fish hook itself.

The slob red drum (aka bull redfish) was soon released, and after chunking a few more of similar size, I switched to a topwater popper and began spraying it along the marsh banks. That’s when it hit me: Whether fishing for reds in North Carolina, Florida’s Mosquito Lagoon, or Houma, Louisiana, I’d been using virtually the same tactics and techniques I use for striped bass (aka rockfish) in the Northeast. In fact, when targeting reds, I called into action the contents of my striper tackle box. That got me thinking: From southern New Jersey to North Carolina, where red drum and rockfish share many of the same waters, why not use crossover tactics to catch both species?

COMMON GROUND

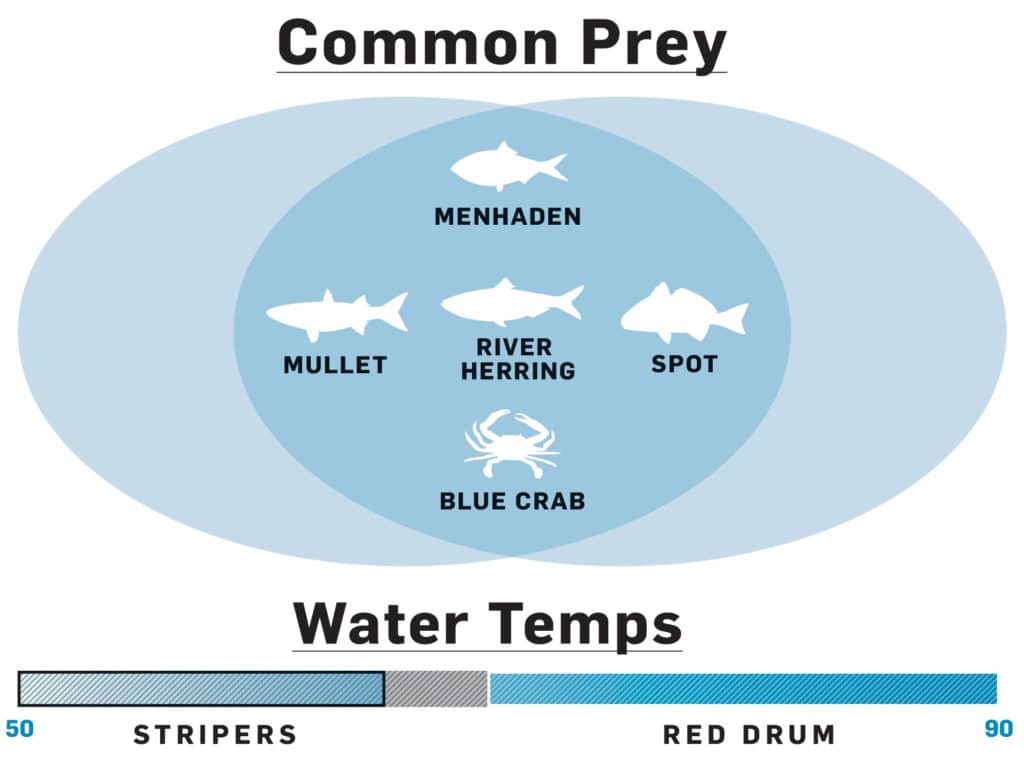

Wayne Justice, education program coordinator at the North Carolina Aquarium at Pine Knoll Shores, confirms there are many similarities between the two species. “Stripers and red drum are both opportunistic and aggressive feeders,” says Justice. “They also share similar growth rates: 27-inch redfish and the same size striped bass are both about four years old, and 40-inchers are around 10 years old. And as they age, both get fatter, but not much longer. Their forage, which includes menhaden, mullet, shrimp and crabs, overlaps, as do the variety of environments they frequent.”

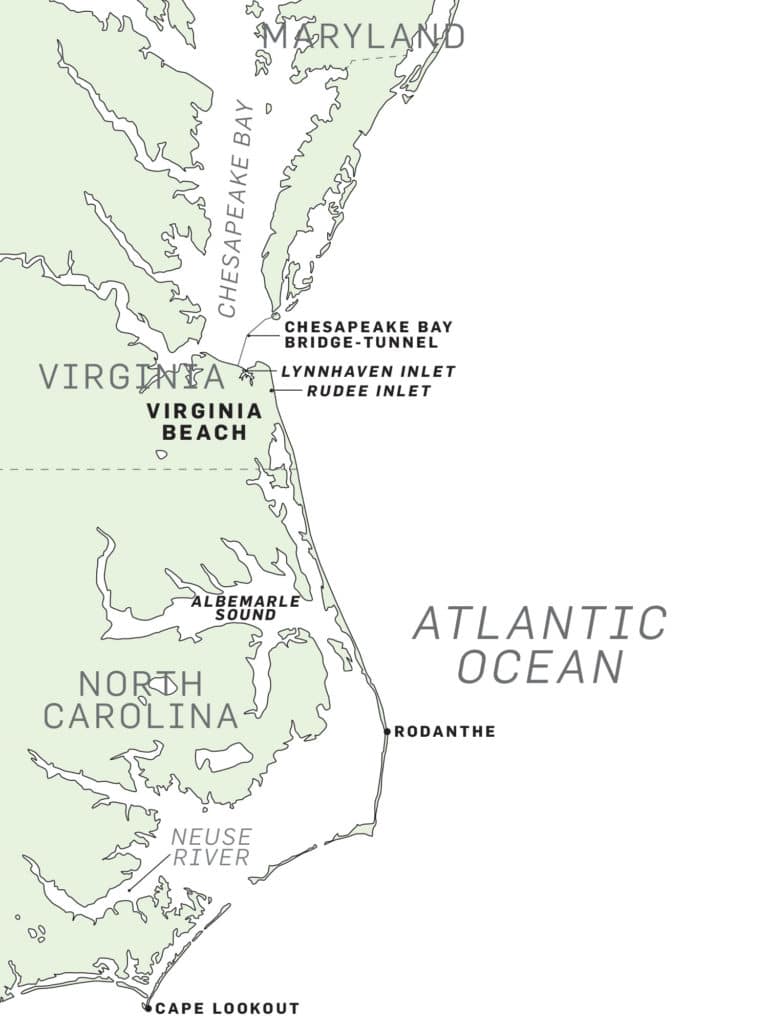

Of course, both game fish move into river systems to spawn, and smaller members summer in the backwaters while trophy 30- to 60-pounders tend to remain oceanside. As for hangouts, reds and stripers frequent shallow flats in the summer, reside in channels and around inlets during spring and fall, and are often found in schools finning in open water in fall and winter. Along the Virginia, Maryland and North Carolina coasts, optimal water temperatures for both species lie in the mid-50s to high 60s. “The farthest south you’ll see both species collide is around Cape Lookout, North Carolina,” Justice says. “Spring and summer is the best time of year to target both species at once in Maryland and Virginia, and fall and winter are best in North Carolina.”

MERGING WATERS

The surf and estuaries throughout the coasts of Maryland, Virginia and North Carolina — including inlets, sounds, bays, coastal rivers and creeks — are prime areas where red drum and striped bass populations converge and forage on the same baitfish and crustaceans.

COMMON PREY

Striped bass (aka rockfish) and red drum are opportunistic feeders, and both pounce on anything that seems like an easy meal. Baitfish and crustaceans that abound in coastal areas when water temps are within their comfort range are the main targets.

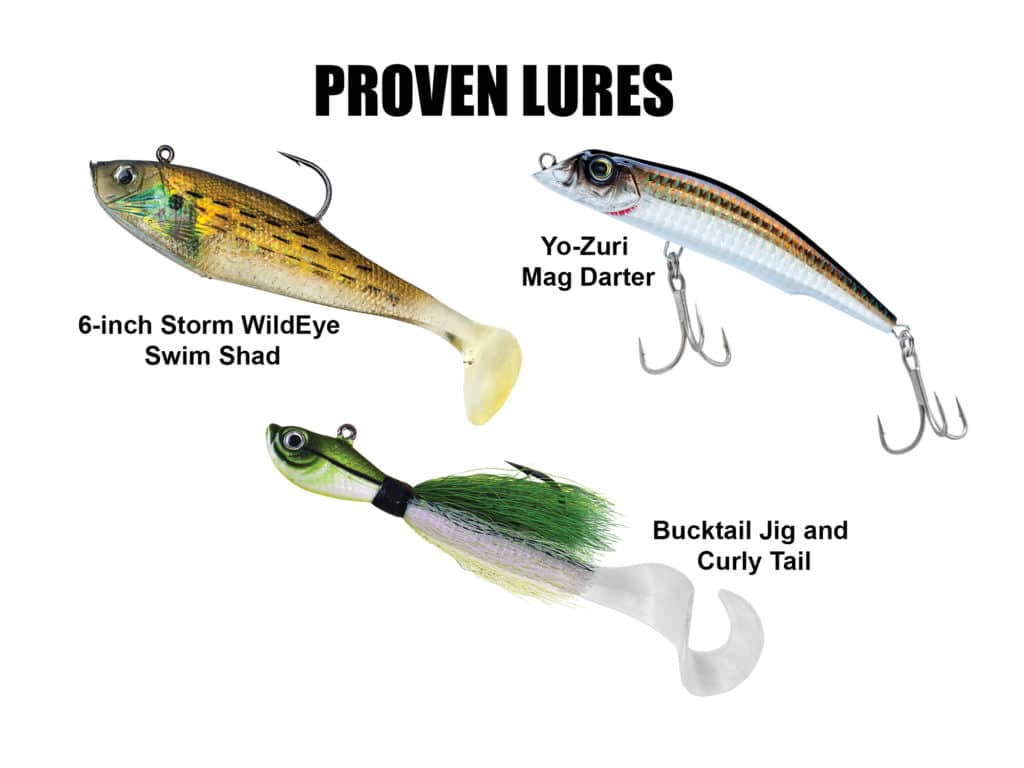

Therefore, soft plastics and hard baits with lots of action and flash work well for both striped bass and red drum, especially in areas where schooling baitfish are present. Red drum, however, rely on their sense of smell more, so scented lures increase chances for a hookup.

And keep in mind that 56 to 68 degrees is the ideal water temperature to encounter both species actively feeding.

CAROLINA RIGS

Ryan White, owner of Hatteras Jack in Rodanthe, North Carolina, experiences fantastic rockfish and red drum action in the sounds and surf of the Outer Banks. “Both use the currents to push bait around,” he says, “and they hang on the edges of rip tides in the cuts and sloughs of the shoals. But the drum usually opt for the windward side, while the bass stage on the backside.” White’s go-to method is to anchor outside the rips coming across the shallow shoals and toss out a fish-finder slide rig with a bank sinker, a short 8-inch leader of 60- to 80-pound fluorocarbon, and a 6/0 to 8/0 Octopus hook baited with a pogy chunk or a live spot.

Heavy gear is desirable when chunking or live-lining in the swashing waters outside the breaking surf and around inlets, but light-tackle backwater tactics shine too. “Pop some corks in the backwaters for puppy drum (smaller redfish),” White says. “As the cork slides up and down, it slaps against the beads and the sound gets their attention.” Rig the cork with a leader long enough to suspend a 1⁄₁₆- to ⅛-ounce jig head tipped with a Bass Assassin or D.O.A. paddletail about a foot off the bottom.

“There’s a ton of uses for the clacking cork. Pop it around jetties, rocky outcroppings, inlet areas, or anywhere there is structure and where normal lures will hang up. It stays above the rough stuff, right in the strike zone.” Popping corks are common down South, but Northern striper anglers would benefit from employing the same tactic along sod banks and around pier pilings and bridge abutments when the water temperatures are stable for both, in the low to mid-60s range.”

CHESAPEAKE TIME

Burnley says that spring is prime time to go live and hit the bay’s eastern shore, anchoring and sending out live blue crabs on fish-finder slide rigs. “You get those large breeder bass coming up to spawn and also get reds moving in to warm up,” he says. “They are both feeding on crabs releasing from the mud.” When the waters cool in October and November, deepwater areas like the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel, Rudee Inlet and Lynnhaven Inlet are hot spots to bounce large swimbaits or big 2- to 6-ounce bucktails tipped with strip baits around the rocks and bridge pilings. “The truly large reds and rockfish, of 30 to 50 pounds, will be hanging on the structure on or near the bottom,” says Burnley. “Come winter, those big fish move out and hang in deeper water off Virginia Beach’s coast.” Then large topwaters, such as the Yo-Zuri Hydro Popper and Gibbs Polaris Popper, incite exciting surface strikes.

ONE-TWO PUNCH

Rockfish and red drum have been colliding off the Eastern Seaboard for hundreds of years, with reds historically spreading north into New Jersey and New York, and striped bass going as far south as South Carolina. The greatest overlap occurs between Delaware and North Carolina, where these two species with very similar habits and preferences fall for the same tactics. Whether you’re looking for reds or rockfish, mix things up a bit and experiment with crossover methods to double your pleasure.

FAST FACTS FOR SUCCESS

Homework: Study charts to identify spots where reds and stripers are most likely to converge. Then review tide tables for peak times to fish.

Find Forage: Look for baitfish schooling, crabs or shrimp flushed by the current, or submerged structure where fish are likely to ambush prey.

Double Trouble: Select baits that both reds and stripers will key in on, or the artificials that mimic the most prevalent prey for the two species.

SWS PLANNER

Mid-Atlantic reds and stripers

What: Striped bass and red drum

Where: From Delaware to North Carolina

When: Year-round

Who: Boating and shore anglers stand a great chance to tangle with both species in the right waters. The following experts take the guesswork out of the equation:

Hatteras, North Carolina Ryan White 252-987-2428 hatterasjack.com

Virginia Beach, Virginia Capt. Ben Shepherd 757-621-5094

Tangier Sound, Maryland Capt. Kevin Josenhans 443-783-3271 josenhansflyfishing.com

SWS TACKLE BOX

Mid-Atlantic redfish and striped bass

Rods: Spinning, baitcasting or conventional, from 61⁄2-foot for back bays to 12-foot for the surf

Reels: Spinning 4000 to 10000 class, baitcasting 400 class, conventional size 20 and smaller

Line: 20- to 50-pound braid, 20- to 60-pound fluoro leader

Lures: 1⁄16- to 3⁄4-ounce jig heads, Z-Man StreakZ Curly TailZ, Berkley Gulp! Shrimp, Storm WildEye Swim Shad, Bomber A-Salt, Yo-Zuri Mag Darter and Hydro Popper, Gibbs Polaris Popper

Bait: Live mullet, bunker, lafayettes (aka spot), blue crab or chunks

Terminal Tackle: Gamakatsu 6/0 to 10/0 Octopus hooks, sinker-slide clips, 3- to 10-ounce bank sinkers, 100-pound barrel swivels