“Here they come again,” I said to my partner, and we both delivered soft plastics on cue, well ahead of a wide swath of nervous water inching closer and closer. We let the lures settle on the bottom and, just before the fish swam over them, twitched and bounced them slowly. Then, wham! We both got hit and set the hook in unison.

Fishing a redfish tournament in Pine Island Sound, Florida, we were staked out, targeting a school of more than 100 big reds that Mike Laramy and I had discovered during scouting. They were creeping up and down a grass flat bordering a heavily transited channel. The fish were foraging, but with extreme caution, and never straying very far from the edge of the flat — their nearest escape route into the safety of the adjacent deeper water.

PATIENCE PAYS

The reds paid no attention to our lures the first and second time they came by. The third time proved the charm. As it often happens in shallow water where resident fish face substantial fishing pressure or boat traffic, the preservation dial of the reds was turned up to the max. But redfish aren’t the only species to become ultra discerning, an affliction many anglers call “lockjaw” because the fish refuse to eat; seatrout, snook, striped bass, tarpon and other inshore game have the condition as well. And even when fish don’t appear skittish and refuse to leave an area, only the perfect presentation results in a strike, and anglers frequently have to wait 30 minutes or longer between opportunities.

It doesn’t matter if you do everything to perfection; a number of details must fall into place for wary game to strike. Your artificial must fall or rise with precise timing, so instead of menacing, it looks like wounded prey attempting to flee. Sometimes fish simply happen to be looking in the wrong direction, or their field of vision is restricted by schoolmates. If they are rooting on the bottom, perhaps it’s mud or other sediment suspended in the water that keeps them from spotting the lure.

STEALTH MODE

Once you locate fish, whether they ignore your lure or spook and high-tail it to parts unknown, it’s imperative to stay calm and persevere smartly, without announcing your presence. It’s not uncommon for a school of fish, like the reds mentioned earlier, to move several hundred yards only to turn around and swing past your boat a few minutes later.

Sometimes there’s more than one school working an area. Other times there are small packs or a number of singles cruising or staging, waiting until the right tide phase enables them to reach their preferred hangouts. That is frequently the case with snook, tarpon, and larger trout and stripers. A fast moving boat is easier for fish to detect, with hull slap and the noise of a trolling motor sounding the alarm.

Anglers who consistently catch fish in popular or easy-to-find places do it by treading slowly and quietly. They either drift or use a push pole to poke about the shallows, then a Power-Pole or stakeout pin to stop the boat in a strategic spot while waiting for fish to come within casting range, or making just enough blind casts to cover a stretch of shoreline or a bottom feature — be it an oyster bar, sand hole, rocks or a stump — before moving another 20 or 30 yards and repeating the process.

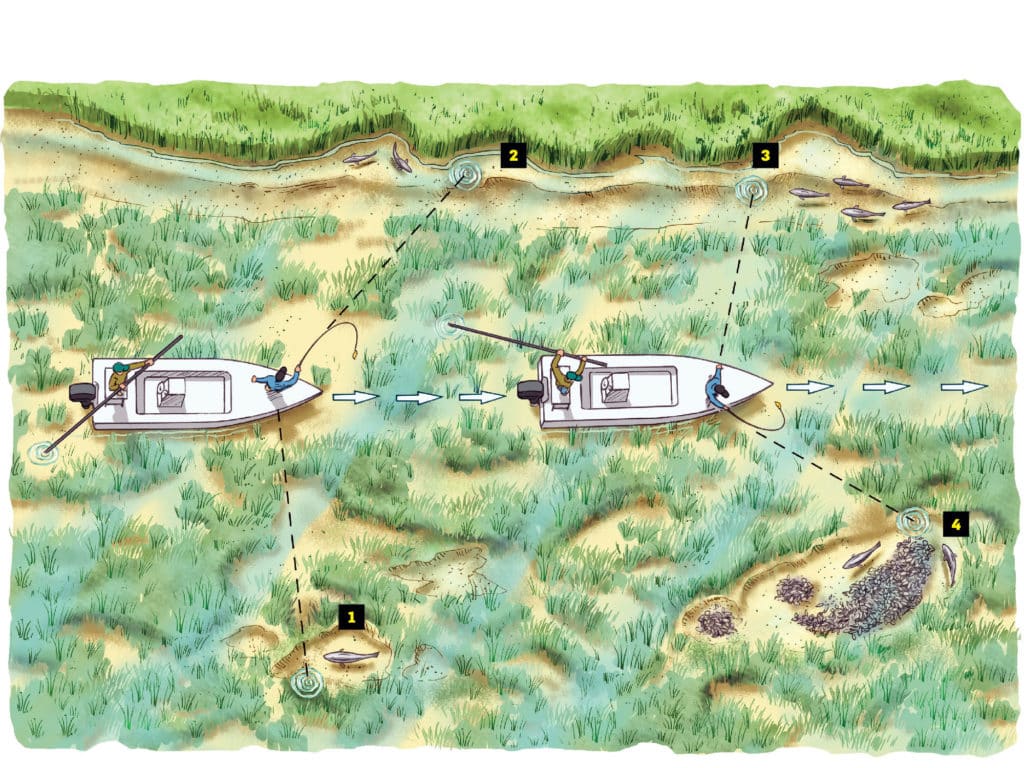

SLOW, QUIET, TACTICAL

The wake from a boat moving across the shallows and the hum of a trolling motor are often enough to put fish on high alert. Cover water slowly and stealthily, using a push pole or a drift sock, and be on the lookout not only for fish but also potholes, troughs, stumps, oyster bars and other bottom features likely to hold fish. First cast around the outskirts, then past the structure, retrieving the lure right over it.

1. Work the edges of a pothole first, then cast past it and bring the lure across the center.

2. When fish lie up on a shoreline, cast away from them at an angle that lets you reel the lure into the strike zone.

3. For fish cruising along a trough, cast 10 to 20 feet ahead and beyond them, then retrieve the lure to meet the fish.

4. Work the deepest water next to an oyster bar before fan casting around the perimeter.

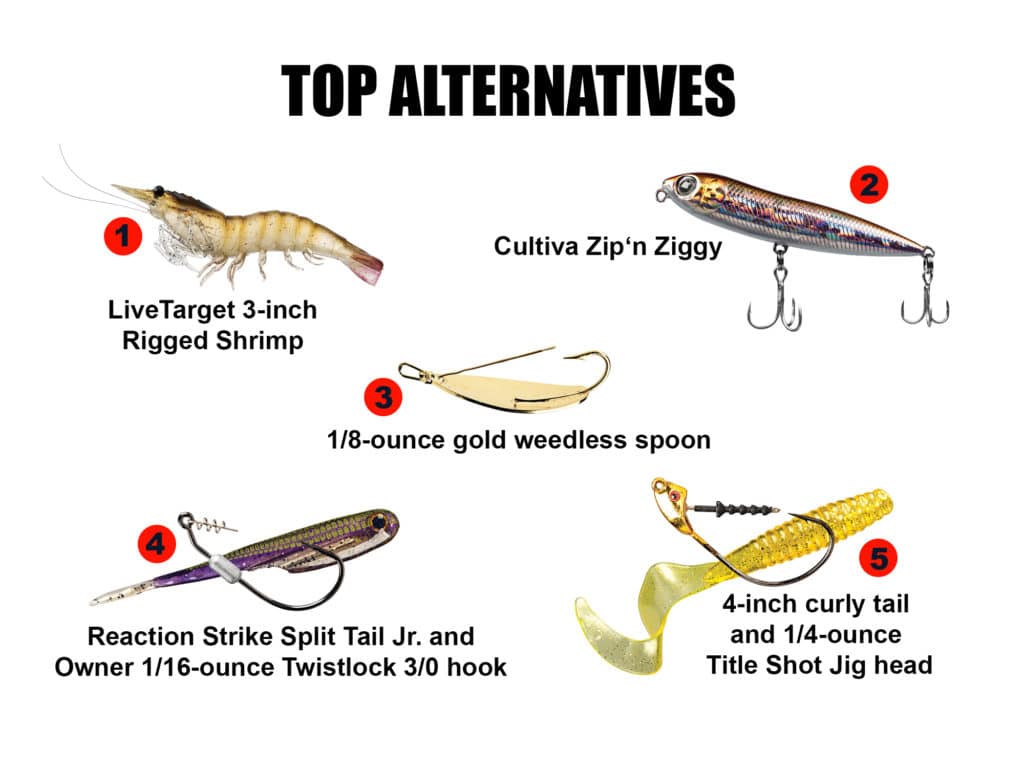

DOWNSIZING

Although I have a lot of confidence in Heddon’s Saltwater Super Spook Jr., the 3½-inch topwater that has produced many fish for me over the years, I’m quick to reach for the equally effective but smaller Cultiva Zip’n Ziggy when I deem it necessary to scale down. Whenever fish are less aggressive and it’s better to stay subsurface, I tie on a MirrOlure MirrOglass, a 2¼-inch suspending twitchbait that weighs only 3/16 ounce. If my plan is to work a gold weedless spoon through the grass, I swap the usual ¼- and ½-ouncers for a more petite ⅛-ounce model, preferably a Flats Intruder by Precision Tackle or the equivalent by Texas Tackle Factory, as both incorporate a larger, beefier hook.

As for soft plastics, I prefer to toss 4-inch jerkbaits, such as Reaction Strike’s Split Tail Jr. or the D.O.A. C.A.L. series, rigged on an Owner weighted Twistlock hook (3/0 and 1/16-ounce or 4/0 and ⅛-ounce), when baitfish are around. In areas where shrimp are the primary forage, I fish a 3-inch (¼-ounce) LiveTarget Rigged Shrimp. And when I must resort to crawling a small lure along the bottom, I like a 4-inch curly tail rigged weedless on a ¼-ounce Fin-tech Title Shot jig, a combo that produces a subtle yet enticing action with a slow retrieve.

SITUATION-SPECIFIC LURES

1.Toss a LiveTarget 3-inch Rigged Shrimp in white, grass or brown shrimp color into troughs, prop scars and potholes. Let it sink, take up slack and retrieve slowly. 2. Walk the dog with a Cultiva Zip’n Ziggy in black-pearl, gold shad, ivory-chartreuse or shiner pattern. It’s most effective in depths of 2 to 4 feet. 3. Slowly crank a gold or copper Flats Intruder 1⁄8-ounce weedless spoon above grass or around oysters. It’s ideal for blind casting or covering water. 4. Twitch and let flutter a Reaction Strike Split Tail Jr. on an Owner 3/0 Twistlock 1⁄16-ounce hook. Cast it ahead of fish or into likely spots with baitfish nearby. 5. Crawl a 4-inch curly tail rigged weedless on a Fin-tech Title Shot 1⁄4-ounce jig across sand or grass bottom. Use it for sight-casting or as a search lure.

LEADERS, LINES AND TACKLE

Smaller, lighter lures usually require you to also scale down tackle, line and leaders. Downsizing the latter makes winning prolonged battles with snook and tarpon — both endowed with extremely coarse lips — more of a challenge, but it also yields more strikes. If you use fluorocarbon — and I strongly recommend it — your leaders resist chafing a bit better, and they are less visible in the water than mono.

Three feet of 20-pound fluoro is my go-to leader in areas with heavy fishing pressure and boat traffic, and I go down to 15-pound when the water is especially clear. Only if I’m targeting snook or small tarpon, or if the spot I’m fishing is laden with oysters or barnacle-encrusted pilings or roots, do I step up to 25-pound. Either way, a 7- to 7½-foot fast-action spinning rod, 8- to 15-pound-class matched with a size 3000 reel loaded with 10-pound Spiderwire Invisi-Braid, is ideal for launching light lures a significant distance and packs sufficient backbone to subdue sizable inshore game.

LOCKJAW: THE MYTH

Seven years on the Redfish Cup tour, coaxing redfish to strike the lure du jour from Texas to North Carolina, forced me to fine-tune tactics for all sorts of situations. I soon learned that in places that are commonly known — perhaps located near a boat ramp, listed on a popular fishing chart or mentioned in the local paper regularly — the resident fish feel uneasy, even when not immediately threatened, and they tend to reject proven artificials.

But unless atmospheric changes render fish inactive for a bit, they won’t stop eating altogether. Scaling down the size of your lures accomplishes a couple of objectives: The lures produce less noise and splash upon entering the water, and they appear less threatening and easier to snatch, all of which increases the potential for close encounters with fish that have to suddenly decide between striking or fleeing. That’s a 50 percent chance of success, and any seasoned angler will take those odds.

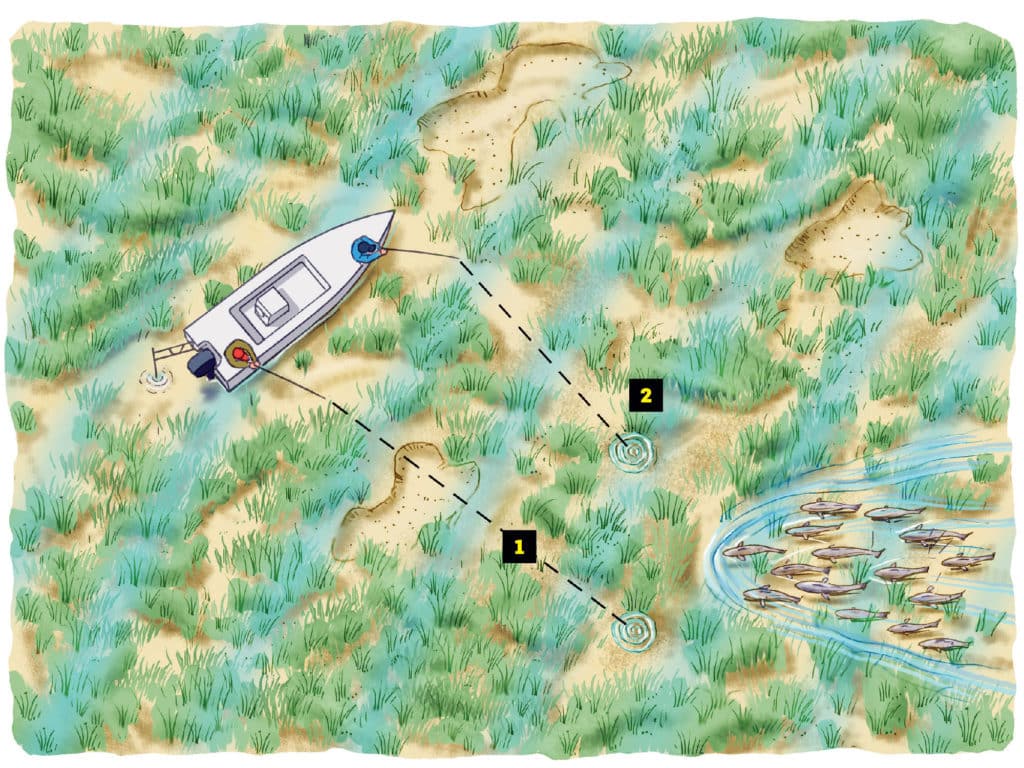

WAIT TO GET AHEAD

In areas where fish cruise the shallows in packs or schools, stake out near a point, a sand or oyster bar, or a shallow bank that forces fish down a predictable path. When you spot an incoming school, study its trajectory and speed to cast ahead and a few feet off center of the estimated path, allowing for last-minute adjustments if the fish shift slightly.

1. Depending on the school size and pace, one angler should cast 20 to 30 feet ahead and 5 to 10 feet right of the leading fish.

2. The second angler should lead the fish just as much but land the lure off the opposite side of the school’s projected path.

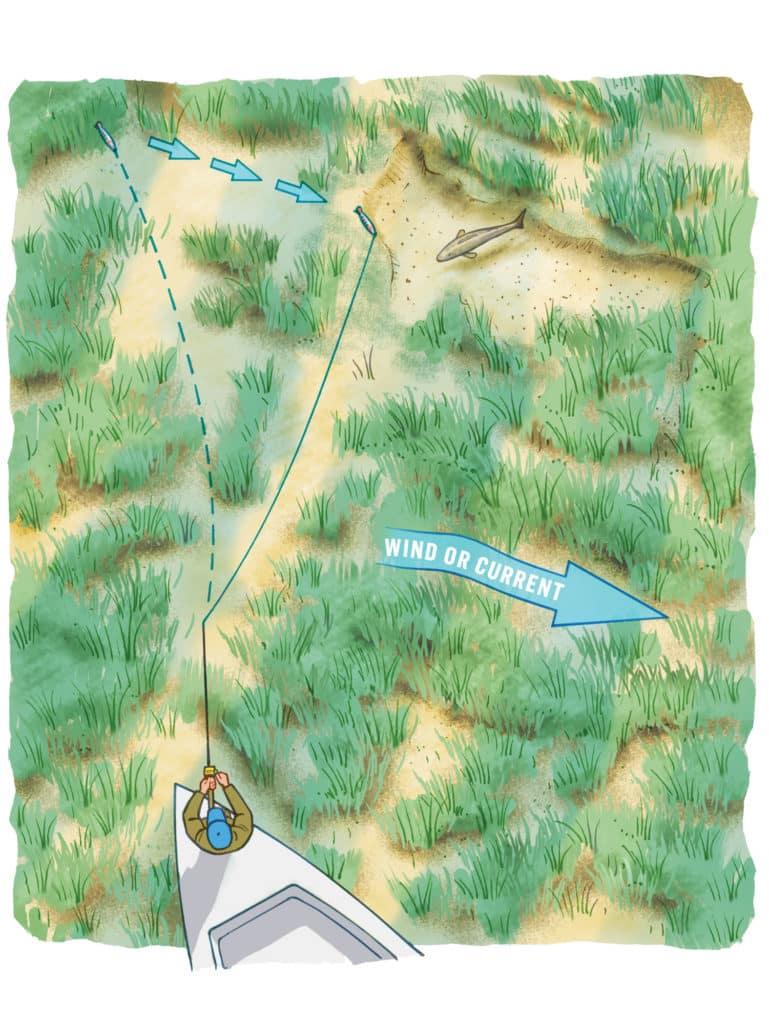

ON THE SWING

Snook, seatrout, stripers and, on occasion, redfish like to wait in ambush in a sand hole or trough. In clear, shallow water, they are extremely sensitive to lures splashing down around them. To catch those fish, set up just out of sight, then cast a light lure up-current or upwind of the target (15 feet or more, depending on the water depth and current or wind strength) and let the wind or current sweep your lure into the strike zone. Close the bail as soon as your lure enters the water, and keep the rod tip high to track the line trajectory.

If the lure is on a collision course with the fish, crank the reel handle a couple of turns. If it looks like it may drift just out of the fish’s reach, point the rod tip at the lure as it approaches the target. This adds a couple of feet of slack line, often extending the swing just enough.

SCENT MAKES SENSE

When fish refuse everything you put in front of them, it’s time to break the glass and pull out those emergency scented baits, pitch them into a shoreline trough or other known fish avenue, let them rest on the bottom, and wait for a fish to pick one up. This tactic may not be particularly stimulating, but there’s no denying its efficacy. A Berkley Gulp! Shrimp fished as described has saved many a day for lots of anglers.