Transitional zones form when two currents or segments of water oppose each other, such as tidal rips, edges of eddies, color changes, surface-temperature breaks and even weed lines. If they exist within the preferred temperature and depth realm of the targeted species, the odds of angling success soar.

Shaken and Stirred

Upwellings and agitated waters disperse plankton, microscopic organisms and forage species into the mid- and upper parts of the water column. On the surface, weeds and debris often collect along these edges. The longer these mini ecosystems stay in place, the more likely they’ll produce fish.

As basic as such features may appear, questions abound on the preferred ways to fish them. Dirty side or clean side? Cooler side or warmer side? Surface baits or deep baits?

Success comes with an understanding of what is transpiring, and how to take advantage of it.

Get Edgy

A major color change, or rip, occurred off Miami recently, where Harry Vernon III and I were drifting live baits. Around 250 feet, the division between royal blue offshore water and dirty turquoise slope water was remarkable. Our efforts inside this edge proved futile, as did those farther out in the blue. Yet tight to the dividing line, dolphin preyed on flying fish. As they pushed to the south, we raced ahead of the foraging dolphin, pitched baits, boxed a few, and repeated the tactic until we caught our share. We remained on the clean side of the rip. A bit later, we went 1 for 2 on sailfish, and also boated a blackfin tuna.

This offshore current pushing tight against the slope water created upwellings and a rip ripe with weeds and bait. Flyers gathered in the plankton concentration, attracting dolphin. Though live-baiting, we wondered what trolling might have produced.

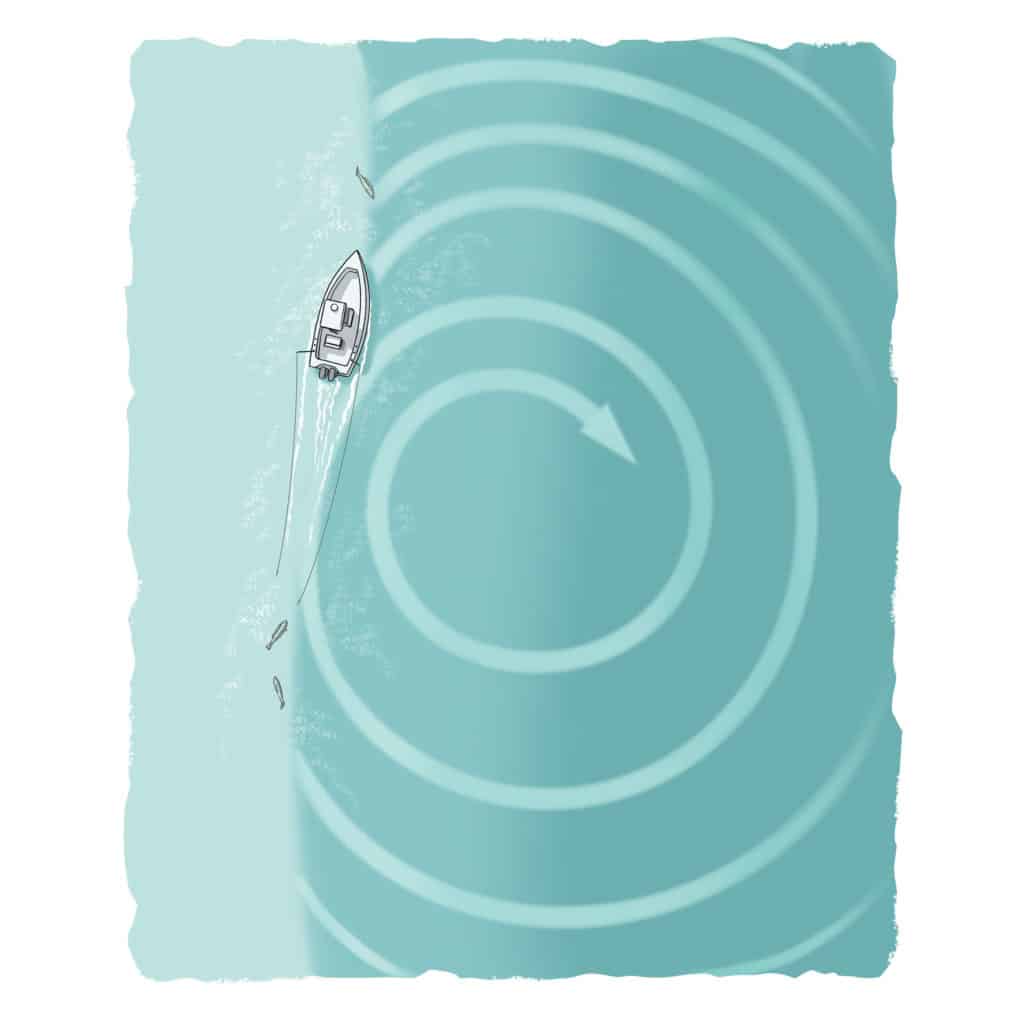

When trolling such rips, I prefer a broad zigzag pattern, mainly on the clean side. I tow baits right on the edge for a bit, then move offshore a few hundred feet before moving back alongside it, usually with a subsurface bait off a flat line, either a deep-diving swimming plug or a weighted, skirted ballyhoo.

Why the blue side? Pelagics are likely traveling in the stronger current and diverting to the edges to feed. If the action is slow, however, we’ll cut across and pull baits on the dirty side, hoping for a change of luck.

The zigzag trolling strategy shines when multiple weed lines and rips lie from a quarter- to a half-mile apart. The trick is to broaden this pattern to cover both zones.

Rip It Up

When a hard current strikes a breeze head-on, tailing sailfish conditions materialize off South Florida shores.

“The Keys see the best of this, especially in April and May,” says Capt. Ryan Wenzel, who operates out of Islamorada.

“The wind needs to be blowing east/southeasterly, paralleling the reef, and the current must be running hard into the wind,” Wenzel says. “There will be three colors of water: green, powder blue and deep blue. I prefer powder blue because the sails show much easier. They’ll be tailing, using the waves to assist their migration against the current. I’ll have a couple guys in the tower looking for tailing fish. We belly-hook live pilchards and pitch them to the sails on spin tackle. On our best day, we released 21 sails. The next day, we took our bay boat offshore and released 14. It’s the most fun I ever had fishing.”

Wenzel idles down-sea, looking for fish. When the current carries them out of position, they run back for a reset. “It’s not only sailfish you’ll find; we’ve caught cobia, dolphin, and seen wahoo and even bluefin tuna tailing,” he says.

Billy’s Wonderland

Few rips are as fabled as those off Louisiana, at the outflow of the Mississippi River. I’ve fished these rips from Venice, catching white and blue marlin, wahoo, tuna and dolphin.

Capt. Billy Wells prefers rips with blue water on one side, and brown river water on the other.

“If it’s clean water against brown river water, I’ll fish the clean side. But if the rip is clean green water on blue, and the blue side is covered with scattered grass while the green side is clean, I’d rather fish the green side.”

Wells prefers rips in the 1,000-foot range, but the most important element is time. “The longer the rip holds, the more grass, bait and gamefish accumulate. This is when our rips really come alive.”

Up Jersey Way

Off New Jersey, Tom Daffin adheres to a similar strategy. “When we’re fishing warm-core eddies in 50 fathoms or deeper, I concentrate on both sides of a break,” he says. “For marlin, I fish the cleaner, warmer water. Tuna can be on either side. In summer, when the hot side is too warm for the tuna, fishing on the dirty side is the way to go. Usually the bait is on the break or cooler side.”

Daffin explains that zones created by an eddy spinning from deep to shallow—where nutrient-rich upwellings collide with the rising bottom—generally produce better than a current moving shallow to deep.

“On inshore structure and rip lines, I don’t put a ton of credence in water temperature or color,” he says. “It’s nice to have clean water, but it’s not a deal breaker to have only dirty water, so long as it holds bait. The key here is bait.”

Layering

Dirty edges of a rip or eddy often form in the upper part of the water column. When fishing tidal or roiled waters, put one rod deep. Edges exist where tainted surface water meets clean water below. These horizontal zones produce.

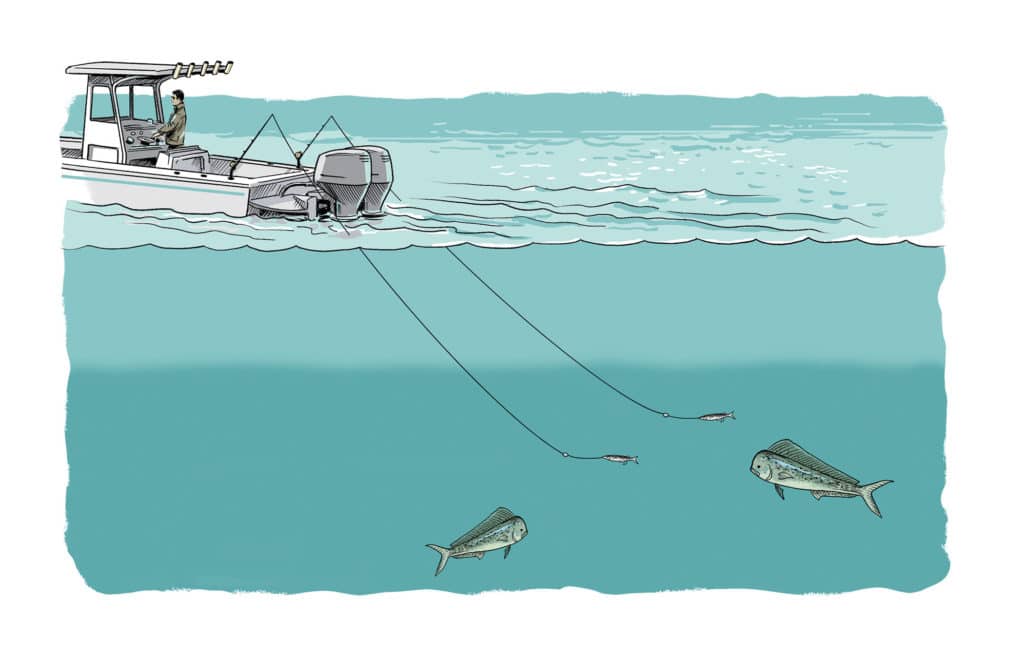

Staggering live baits at different depths with downriggers or weights is standard for king mackerel, especially whenever slow-trolling or drifting tide lines and rips.

Surface baits entice predators holding shallow on the rips, while subsurface baits catch smokers holding deeper in the cleaner water.

Ditto for trolling the Venice rips. Here, the dirty edge is merely a layer of surface water, and big wahoo, tuna and billfish come to baits deployed in the clean water beneath it.

Do Your Recon

Two companies specializing in locating surface-temperature variations and ocean-circulation features that lead you to fish:

Roffs

321-723-5759

SiriusXM Fish Mapping

855-796-9847