Success in any worthwhile endeavor always begins with a solid foundation. The same applies to both inshore and coastal fishing, where correctly reading and understanding the bottom provides essential details that’ll guide your positioning, bait choices and timing, ultimately leading to more productive and consistent results.

Hard Facts

Serving as forage-gathering centers, current breaks, space heaters and sunning stations, solid structures and hard-bottom composition that punctuates barren or muddy expanses are definite fish magnets. In the Mississippi Delta, Capt. Anthony Randazzo notes that hard sand flats, oyster bars or shell reefs over a mud-bottom bay draw baitfish and attract more speckled trout, redfish and flounder.

Likewise, a rock pile on a muddy coastal stretch congregates fish that would typically avoid the area. The same principle applies to eroded roseau-cane points in duck ponds with mostly muddy bottoms, common in the coastal marshes of Louisiana and Mississippi.

In the largely muddy Everglades backcountry, Capt. Rick Stanczyk explains, snagging your jigs on isolated rocks, sponges and coral patches, or feeling the telling clunk or crunch when your push pole makes contact with solid bottom is a sign that your surroundings probably hold both natural forage and hungry predators looking for a meal.

Stanczyk also points to Florida Bay’s random hard-bottom patches, which draw seasonal visits from tarpon and snook while also housing gag and juvenile goliath groupers, as do similar areas farther up the Gulf Coast. Idling and graphing reveal the occasional promising spot, but Stanczyk watches for rolling tarpon and then explores the immediate area. While fishing bottom baits for tarpon, a snook, redfish or grouper bycatch often confirms he is on good, hard bottom.

Capt. William Toney of Homosassa, Florida, targets west-facing points because incoming tides scour the limestone bottom, creating habitat for crustaceans and baitfish, and depositing mud and other unproductive sediment on the east side of many small islands and keys in the area. Rising tides usher snook, trout and redfish onto these clean, rocky edges.

Productive Grounds

In addition to rock, there are several other types of hard bottom that also pay dividends for anglers.

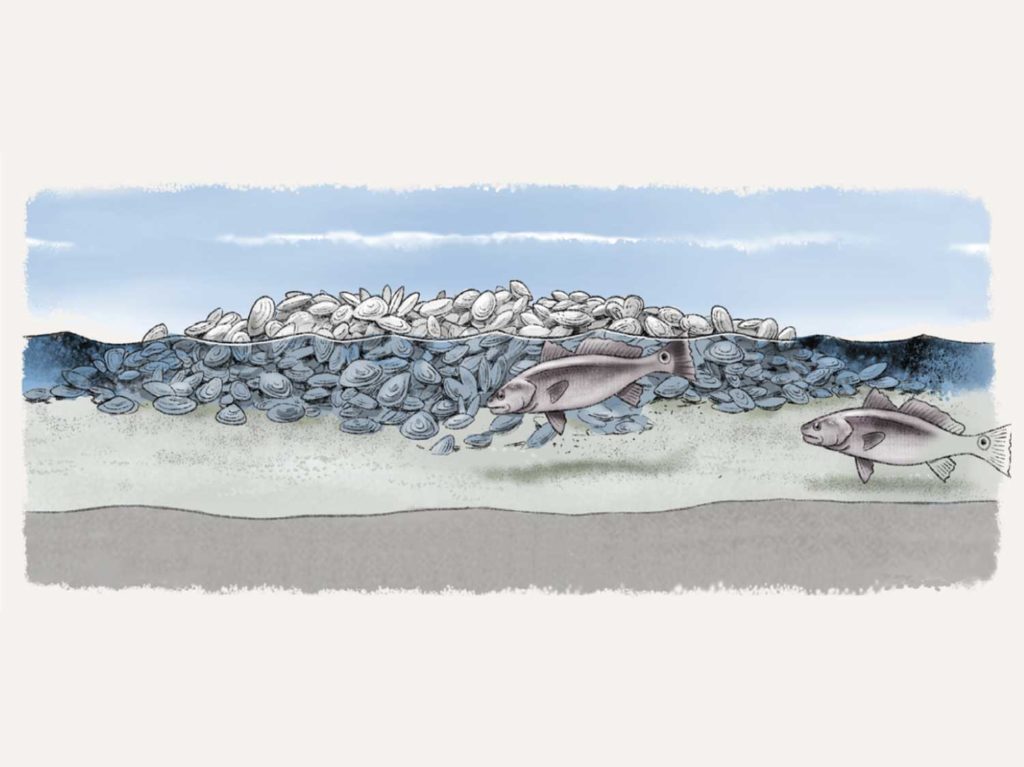

Oysters, whether the natural oyster bars flanking mangrove shorelines in Florida, the sprawling oyster mounds extending from marsh banks in Georgia and the Carolinas, or the commercial oyster reefs along the Mississippi Delta, offer food and current breaks for prowling inshore game species, which tend to hold on the deeper side during low tide and march up the mollusk structure with rising water. Turns, points and flow-through gaps in the oysters, by the way, are often the sweet spots.

Likewise, crumbling piers, docks, or the platforms of nearshore oil or gas rigs in the Mississippi Delta indicate bottom rubble—and often oysters—that offer similar benefits to various popular angler targets. Other man-made hard-bottom sites within coastal bays, including wrecks and artificial reefs made up of construction rubble or concrete reef domes, hold snapper, grouper, sheepshead, grunts and porgy. Bottom rigs work fine, but trolling plugs also do the job, especially on grouper.

Riprap and scattered rock or shell, especially off the tips of islands, prove attractive feeding stations on high -water. And unique to Texas’ Baffin Bay, worm rock, the hardened calcium-carbonate tubes left by serpulid worms some 300 to 3,000 years ago, created reefs that attract redfish and giant speckled trout.

Grass Class

The cradle of life for southern estuaries, seagrass abounds with crustaceans, invertebrates and small finfish, providing plenty of forage for gamefish and, in turn, ample opportunity for anglers dialed in to the high-percentage zones.

On Florida’s Gulf coast, from Charlotte Harbor to Tampa Bay, Capt. C.A. Richardson looks for the flat, ribbonlike stalks of turtle grass on the bottom to find speckled trout, redfish and snook. The soft-bodied trout hunt and seek shelter in the grass, while the reds and snook stake out potholes and depressions amid the grass, where they can wait in ambush or take advantage of the greater visibility to pick off passing prey not obscured by vegetation.

Seasonal water temperatures determine depth, but locating flats with thick grass and deep water nearby is money, not just for the three game species mentioned, but other favorites as well. In South Florida waters, for instance, the same holds true for bonefish.

Redfish also graze for crabs, shrimp, worms and other morsels over salt-and-pepper bottom, a mix of sand and thin, cylindrical manatee grass. Meanwhile, limestone outcroppings, with their typical tidal furrows, offer prime holding spots for lurking snook.

Depth Perception

While drop-offs, cuts, channels and holes offer low-tide lobbies where fish stage until water rises, it’s important to note that water-temperature stability increases with depth, which becomes increasingly essential to success during the cooler times of year. However, the right approach varies with location as well as the season.

“Most smaller channels and drains in the backwaters are shallower and tapering,” Randazzo says. “We start fishing as shallow as possible and work toward deeper water. Larger channels closer to the Mississippi River offer deeper water and sharper depth changes, where we target fish feeding in eddies,” he adds.

In Florida, snook stack in deeper water off island tips, and in creek bends and troughs along mangrove shorelines. Cuts and troughs perpendicular to mangroves, seawalls or jetties are the approach routes.

Stanczyk finds that cuts and channels slicing through the grass and mudflats in Florida Bay hold a variety of bottomfish, with the mix of species and sizes increasing with proximity to the Gulf.

Creek Complexion

Tides carve twists and turns with deeper water on the outside bends of coastal creeks, creating ambush pockets for gamefish. Conversely, the bars and shallow flats on the inside edge of creek bends allow predators to pin their prey against a sideline.

Some fish move in and feed during incoming tides, while others use structure for ambush feeding during falling water.

Arteries draining marshes and other backwaters create funnels that deliver a bounty to waiting predators during falling tides, precisely why it pays to focus on fishing the mouths of such drainages.

“A creek mouth will be scoured out white, but then you’ll see a dark sediment line where the current drops the sediment,” Richardson says. “Fish sit in that sediment because the darker bottom is warmer in cooler times, and they’re more camouflaged.”

Seasonality

The availability and activity level of many target species varies with the calendar. In Homosassa, for example, Toney says coastal rocks that hold snapper, sea bass and mackerel during the warm months host pre-spawning sheepshead in winter.

As temperatures dip, inshore gamefish seek more favorable conditions in dead-end sloughs, pipeline or residential canals, and protected waters where mud or other dark bottom collects heat. But seasonal hydrology influences the fish’s bottom preferences in many areas.

Troughs, depressions and backwater holes along the Gulf Coast shine during negative winter tides, when water levels drop below mean low tide. Cold fronts often amplify the impact as strong winds push outgoing tides to lower levels and hinder rising water during incoming tides.

When spring finds a high Mississippi River spewing muddy, cold fresh water through every cut and passage, anglers flee the turbid flow and target areas with harder sand bottoms and good tidal influence, which warm up faster.

Factor bottom composition into your inshore or coastal fishing strategy, and you’ll keep the rods bent.