Prince Edward Island tuna the size of submarines crashed chunks alongside the boat as I locked the rod gimbal into place and slipped the harness straps onto the lugs of the Penn 80VSW. It was packed with 1,300 yards of 200-pound braid and topshot, and mounted on a custom 5-foot stand-up rod aimed at producing enough stopping power to beat and release one of these massive fish within the one-hour time period decreed by Canadian fisheries law. The captain was pulling line off the rod tip so he could toss the herring impaled on my hook into the next handful of chunks when he turned and asked, “You ready?” Silly question!

As soon as the bait hit the water, it was inhaled by an 800-pound-class bluefin, and when I pushed the lever up to engage the initial 45 pounds of drag, the fish reacted with a blistering run, stripping half the line off the reel. As the fight progressed, I increased the drag incrementally for each successive run until it was maxed out at more than 70 pounds. In the end, the fish was beaten and released in 44 minutes, and victory high-fives ensued. That afternoon, my friend Brett Surgent would fight and release a grander on the same outfit, and he had never caught a tuna on stand-up gear before.

You don’t have to be a weight lifter to do it, although being in good physical shape is a plus. It takes matched tackle, and a knowledgeable coach to teach you the ropes. Fortunately I learned from some of the best. My initial attempts were with sharks, yellowfin and bigeye tuna in the mid-1980s, but it was off California on the Royal Polaris that I began to understand the synergy between tackle and technique. Sometime later I was tutored by stand-up guru Dennis Braid, an incredible angler who developed the belt-and-harness systems and techniques that made it possible to beat the giants in PEI this past September.

Angler’s Advantage

Stand-up tackle — designed to provide anglers with a mechanical advantage over big fish — works on the principle of the lever and fulcrum. The tuna is the load, the rod is the lever, and the belt and harness create a fulcrum point that allows the angler to use his body weight to counter and raise the load. However, there are additional factors that figure into this equation: the fish strength, the flex and rebound of the rod, and the drag pressure generated by the reel. The drag acts as a buffer between the load and the lever. At no point will the angler lift more than the pound setting at which the drag slips, while the flex of the rod absorbs shock and aids lifting power much like a bow launches an arrow, only in slow motion. The system works so well, it allows the angler to balance body weight against drag pressure when the tuna runs so he is expending very little energy while tiring the fish. When the fish stops, the angler uses body weight to turn and pull the tuna closer to pick up line.

Assembling a stand-up system starts with the pound-test of the line, which determines the drag pressure that can be exerted. With 50-pound line, a fighting belt that positions the rod gimbal at the top of the thighs should be matched with a lightweight harness that fits just above the hips. It’s paired with a relatively soft 5-foot-9-inch to 6-foot rod, which has plenty of lifting power for a maximum drag setting less than 30 pounds, while allowing the angler to crouch into a relaxed fighting position. You can use any variety of two-speed lever drag reels, as long as they offer adequate drag and line capacity. For 50-pound line, I prefer a 30-wide like Penn’s 30VSX loaded with mono, but with braid the reel size can be even smaller than that.

For 80- and 130-pound line, everything is taken to the extreme, with the angler facing up to 70 pounds of drag. Rod length is no more than 5 1⁄2 feet for 80-pound, and even shorter for 130, with a fast action and much stiffer butt section. Reel size increases to hold as much as three-quarters of a mile of line. In PEI, I used Braid’s PowerPlay system. The gimbal rests on drop straps at mid-thigh and moves the fulcrum point lower to work with the shorter rod, providing more mechanical advantage to the angler.

Fighting Strategy

In a properly conducted fight, the line should always be moving. If the fish isn’t pulling drag, you’re pumping and gaining line. The fish should never be allowed to rest, but you are able to when the fish is taking line. On the initial run, with the drag at prestrike, you want the tuna to make a long, fast run under moderate pressure, burning up lots of energy. When it stops, push the drag up closer to strike and start pumping. You’ll gain some line, but the fish will still be fresh, and when it turns to run, it will be against increased drag. When it stops again, push the drag up to strike and pump with an even cadence, turning the fish back to the boat. Frequently you can get the fish to turn and run toward you: If it does, crank as fast as you can in high gear to take advantage of the opportunity. Experienced anglers say this strategy breaks the fish’s will. As it tires, counter each successive run with more resistance to make the fish give up.

The endgame is always the same. It’s signaled by the fish transitioning into lazy circles under the boat. Sometimes those circles start a few hundred feet down, at other times, it’s much shallower. This is when the angler is forced to lift the load as the fish is directly below the boat. With drag at max and the rod loaded with your body weight, you can pick up a foot or two of line per pump. Take advantage of the circling. When the fish is moving away, try to relax and hold position, but when it starts to come around toward the boat, start pumping. Identify the cadence, and you can get an extra turn or two on the reel handle with each go-round, so you gain hard-earned line with less effort.

Tangling with a giant on stand-up tackle was something I’ve had on my bucket list for a long time, and I managed to accomplish it two weeks before my 62nd birthday. Reinforced was my long-held belief that proper tackle and technique beat sheer brawn every time.

Setting the Drag

Ready, Set … Adjust your gear and get to know it long before you’re on the water. Put on the harness system, lock the rod in the gimbal, and attach the harness straps to the reel. Stand straight and adjust the length of the straps so the rod is about 15 degrees above horizontal. This is ideal when a fish runs. When pumping to gain line, the rod should not rise above 45 degrees; any more and you’ll lose lifting power and stress yourself.

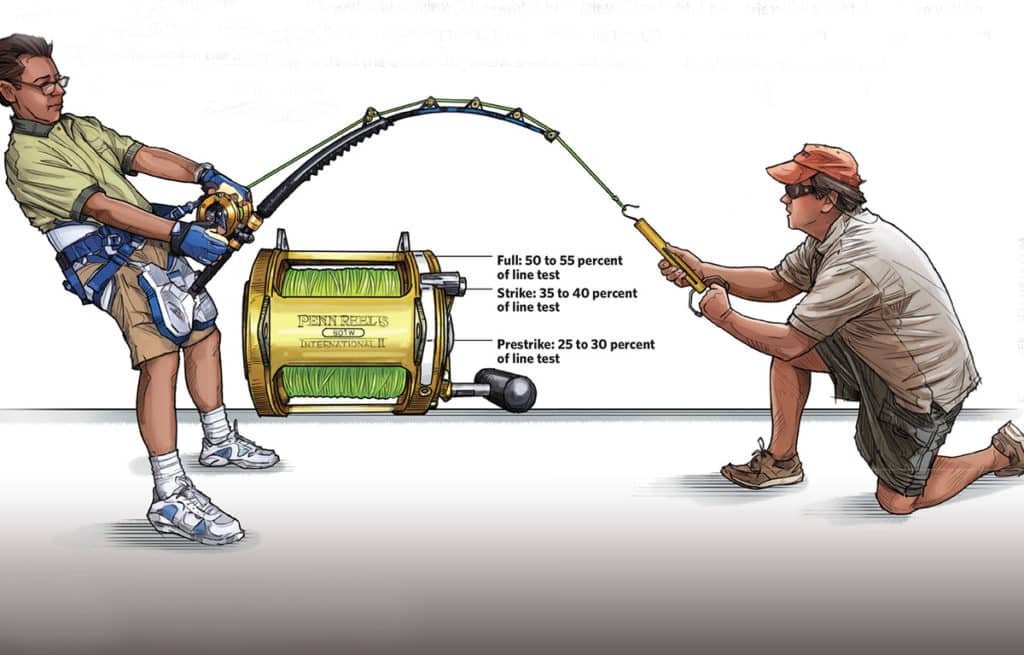

Now set the drag while someone pulls the line, fastened to a scale, down and away from you. When setting the drag, first warm the drag washers by pulling a few yards of line off the reel at modest pressure, with the rod under mild load. Set at least three drag position markings on the reel. If the reel doesn’t have numbered marks on the side plate, waterproof tape works fine. The first setting is “prestrike” at 25 percent to 30 percent of the break-strength of the line. “Strike” is 35 percent to 40 percent, and “full” is 50 percent to 55 percent. To beat big tuna, the ability to generate maximum drag pressure within a line rating is critical.

Once you’ve established these settings, have someone run line off the reel at each one while you adjust your balance as the drag slips. Then pump them back using your weight to load the rod and reel down to retrieve line. Practice switching the reel from low to high gear, and feel the difference in cranking power and retrieve speed. With big fish and heavy line, low gear can be your best friend in a fight, but there will be times when you have to quickly switch back to high gear to pick up line.