Striped bass are an ideal game fish for many reasons, but one of the most notable has to do with the fact that they feed in so many different conditions. I can’t think of any other major game-fish species that can be found in such diversified water. Stripers can swim freely in heavy rolling surf or along rocky shorelines with 10-foot waves crashing into structure. Another plus is the simple fact that they primarily live in the Northeast, which just so happens to be the most populated region in the United States, making them accessible to thousands of anglers.

Stripers were my first exposure to fishing. Nearly 60 years ago, using a light spinning rod and an Uppermen bucktail, I caught my first bass; about 10 years later I took my first on fly. In those days, fly-fishing for these great game fish was an oddity and was a tactic that seemed frivolous to most anglers. Fly-fishing was for trout or in southern locations for tarpon and bonefish. Back then, most anglers felt fly tackle was not suited for rolling surf, big rips or ocean beaches, where casting distance was often the name of the game. But these anglers were wrong, and the sport grew until there were in some locations more anglers fly-fishing for bass than there were spin anglers. Into the 1990s and early 2000s, the boom of fly-fishing in the Northeast continued to grow. Striper populations were coming back strong from a catastrophic collapse that occurred in the ’80s — the fishery was thriving. There were solid numbers of fish, not the large fish we saw in the ’70s and early ’80s but indeed plenty sizable for fly tackle. While the spring and fall runs were very healthy ones, in all actuality, the spring runs were stronger than the fall runs, which was opposite to the fishery of the ’70s and ’80s.

Then something happened. Around 2005 or 2006, the fishery seemed to taper off. Other anglers I talked to noticed a drop in numbers even earlier than that. All of us hoped it was due to a lack of bait or a change in habits, but as the years passed, the numbers continued to fall and fishing success dipped. Knowledgeable anglers still find some fish, and in New Jersey, fishing is still good because large concentrations of menhaden are off the state’s beaches. From year to year, some sections of Maine and locations such as Rhode Island, Montauk, New York, and some areas in Long Island Sound still see bright spots, but generally up and down the coast, fishing is off.

The outer beaches of Cape Cod, and the islands of Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket, Massachusetts, have seemed to be the hardest hit, with the shore fishing getting worse each season. Many anglers began to blame the drop-off of striped bass on the growing population of seals in these areas. And it’s accurate to say that beach fishing there is off more so than boat fishing. Without a doubt, the effects of well over 120,000 seals not only chasing stripers but also consuming them makes matters worse. Some boat captains claim there are still good numbers of fish, and this might be true. The huge offshore rips that run from Monomoy Island to east of Nantucket and then west to the Vineyard are vast sections of water seldom affected by fishing pressure. In fact, this water was a stronghold, a sanctuary if you will, for stripers during the last collapse. These areas still hold fish and it is hoped they will continue to do so. There are reports from blue-water boats looking for tuna spotting large schools of stripers well offshore in deeper water. This could be due to a lack of bait or a change in stripers’ habits; perhaps with fewer fish competing for food, there is no need for the fish to move into shallower water or along the beaches to feed. In my early fishing days, we seldom found fish on big shallow flats. Only when the numbers of fish increased and big baitfish became less plentiful did flats fishing become popular. But why are fish suddenly not feeding on the flats or along the beaches as they did only a dozen years ago? It keeps coming back to fewer fish.

Evidence of a drop-off in the striper fishery is seen in the lack of anglers traveling to locations like Cape Cod and the islands to fish. Ten to 15 years ago, Cape Cod hosted large numbers of surf anglers, especially in the fall. Beach buggies were everywhere. Most were spin fishermen, but at the Vineyard fly-anglers often dominated the water. And it really didn’t matter because the fishing community was out enjoying its mutual passion — fishing for striped bass. Now the number of anglers that come to Cape Cod in the fall is down to a trickle. The last few years, in most cases, I had the beaches to myself except for the seals, which have now taken over.

There has always been mixed emotions with stripers. In Massachusetts, there are many commercial rod-and-reel anglers. I first saw evidence of this while doing the early outdoor shows in locations like Worcester. I was a young gun, a fly-rodder who believed that stripers should be a game fish and released — not a popular opinion in those days. I participated each year in the Saltwater Round Table at the Worcester show where Frank Woolner, the first editor of Salt Water Sportsman, liked having fun setting me up as a radical who wanted every striper released. It was in good humor, and at the same time, it allowed me to make my point — stripers are far too valuable to kill. When the collapse of the striper fishery came, I remember Frank saying, “I don’t know how Tabory knew about the stripers problem, but he was right.” Back then, I had no knowledge of what was wrong; it was just my moral belief that it was right to release the majority of them. I never was against anglers keeping a special fish or eating a few each year; it was the slaughter of fish for the market or to fill a box for a charter business that upset me. Before the moratorium, there were virtually no regulations to protect the striped bass. For some anglers this meant “kill ’em all.” It was this mentality that sparked the collapse of the fishery.

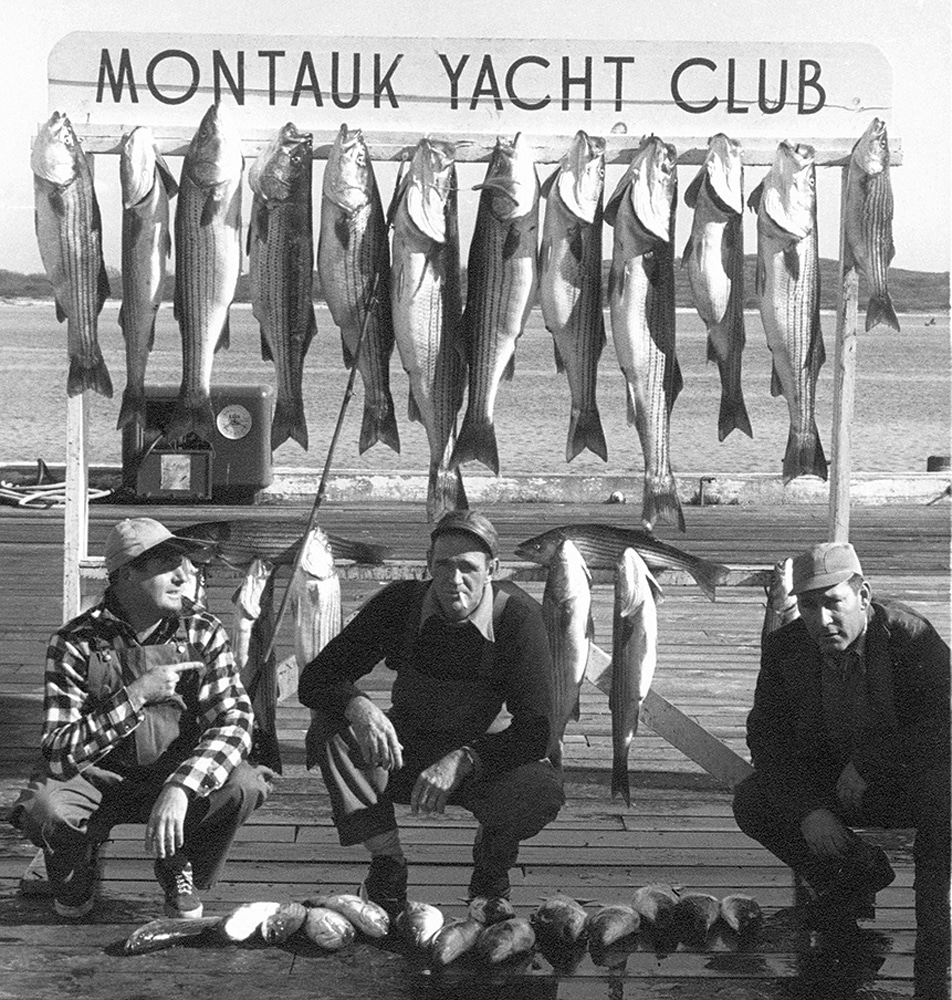

In the 1940s and ’50s striper numbers fluctuated, but by the early ’60s the numbers increased as did the young-of-the-year. From the early ’70s, striper numbers continued to grow, with 1973 recording the largest commercial landing in modern times. Fishing for bass was at an all-time high with large numbers of big fish taken from the beach. Some articles written in outdoor publications bragged of the large numbers of big fish piled on the beaches. This was when commercial beach-angling became very popular, with catches of more than a thousand pounds of stripers on a hot night. This certainly was not the norm, but it was definitely possible and is an accurate gauge of how good the fishing was at that time. But even on an average night, these anglers were killing many fish with no restrictions of numbers. Nobody ever thought it would end; the fishery seemed to remain strong. The market price of stripers was high and anglers were making big money.

The average spin angler experienced fishing that was often unheard of. Along the beaches, catching a 20- to 30-pound striper was possible on any outing, with a 40-plus-pound fish still a very real possibility. I got small glimpses of this possibility, but I was able to seriously fish only the end of this run of big fish, and it was still good especially by the standards of someone who had never fished the cape and islands during the best years. In the early ’80s, everything changed. The numbers of stripers decreased rapidly, and at the same time, young-of-the-year numbers drastically dropped. With no regulations in place to prevent further damage, anglers continued killing these big fish; all stripers over 15 pounds are females, which means they were killing the brood stock. There was another problem, a void of smaller fish. Most of the fish were bigger. In the waters off the cape and islands, there was a time when fish under 15 pounds were almost nonexistent. The ’80s, unlike the early ’70s, had fewer fish, but when you hooked up the fish were 20 to 40-plus pounds. Yes, it was an exciting time to fish, but as these larger breeder fish disappeared, nothing replaced them. The stocks of fish from the Chesapeake Bay, the major supply of stripers along the East Coast, had a grim future. The Hudson River stocks were stronger, but they supplied fish to a much smaller area.

In the early 1980s, the cause of this devastating drop in striper numbers was lack of regulation. Actually, there could have been a blessing in disguise in that the fishery collapsed so fast that drastic measures were needed quickly. It was the first time in the history of the striper fishery that sport anglers and commercial anglers agreed on an issue — stop killing fish. It took a little time, but eventually a moratorium was established protecting stripers. It was a tough measure, but necessary, and slowly the fishery began to strengthen.

One thing that has happened in the last five to six years is people not facing the facts — stripers are in trouble again. Some anglers have lowered their expectations and now refer to as a good day’s fishing a situation that years ago was only a fair to poor outing. Newbie anglers simply believe catching a few fish is what is to expect. The Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission (ASMFC) is turning a blind eye to this very serious problem, often siding with commercial interests. In Eddies, a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service magazine, an article by John Bryan appeared in the Spring 2012 edition about the successful restoration of striped bass. The proof offered is a phone call from an angler fishing Montauk who claimed that the fish were so thick you could almost walk on them. That kind of thinking is just sad. To see the problems, fisheries management needs to look at how few anglers travel to locations like Cape Cod to fish for stripers compared with 10 years ago; or examine how the numbers of stripers entered in the Martha’s Vineyard Derby as well as the sizes of fish have dropped in recent years. The 50-pound benchmark striper is a thing of the past. Sales of nonresident over-sand beach permits has dropped significantly in the last five years as well. Even with cell phones and the Internet broadcasting any action, fishing is generally slow for the average angler. A quote from John Bryan’s article addressing the decline that occurred in the late ’70s states that “over harvesting, especially of spawners, was identified as a major reason for the decline, and strict limitations were put in place.” Why would fisheries managers, who openly admit that harvesting too many spawning females caused the last decline, go out and do the same thing again, allowing anglers to take two fish a day over 28 inches?

I am not using just my fishing success to judge the health of the striper population; I’m getting information from many other anglers that fish a lot harder than I do. I believe charter captains using effective techniques like wire-line trolling or bait anglers fishing in deep water are not true indicators. In my opinion, the best barometers are the fly and surf-plug anglers. Fly-fishing is the most difficult way to catch stripers, followed by surf fishing with artificials. In the last six to seven years, say anglers I know who fish using these techniques, fishing is falling off in many New England locations, and in the last three years, it’s gotten worse. Ten years ago, locations in shallow water in late spring in Cape Cod Bay would usually have hundreds of fish each day; now they have 30 to 40 fish, sometimes half that. This is not based on one year but more than five years of checking these locations. Now, if there is a small push of fish one day, the next day is often dead. In the good years when you hit fish, they were usually there for three to four days or longer. In the late 1990s in May, the “bowl” just south of Chatham Lighthouse on Cape Cod might have had a hundred anglers fishing — now it’s mostly empty. Guides I know that specialized in light tackle and fly-fishing for stripers have stopped doing trips or fish for other species.

There is one easy solution to this problem: Stop killing the breeders. Both recreational and commercial fishermen target larger fish because regulations require that practice. A slot limit similar to what the state of Florida has for most of its game fish would stop the killing of females. In the Northeast, only the state of Maine has a slot limit. If stripers were protected from 28 inches to 48 inches, they would have at least eight to 10 years of freedom to spawn. A one-fish-a-day, 22- to 26-inch slot limit would solve this problem, letting anglers keep a fish while saving the fishery. When it comes to fisheries management, Florida is the example we need to follow. Unfortunately, because of commercial interests a slot limit will be a tough sell. Even most six-pack captains would fight any laws that would take away from their business.

Obviously, the best solution would be to make stripers a game fish. However, I’m afraid the only way we will get game-fish status is if we lose this great game fish one more time.

Striper Report 2013

Striper Report 2013

Striper Report 2013

Striper Report 2013

Striper Report 2013

Striper Report 2013