For most anglers, fly-fishing for striped bass beckons images of screeching birds over busting fish on a windy fall day, or perhaps of stalking that quickly moving shadow on a white sand flat in June. Images such as these are so synonymous with striped bass that it’s easy to overlook the isolation and natural magnificence of the salt marshes that can be found in the mid-Atlantic and Northeast, often within sight of major metropolitan areas. Avoiding the hustle and bustle of city life is of course attractive, but what’s even more appealing about these salt marshes is the abundance of marine life that can be found.

The whole vibe in such areas is steady, slow and deliberate. Even the subtle bird life, embodied by an egret quietly stalking bait in slow motion, is in stark contrast to the screeching gulls and frantic run-and-gun pace of the fall. Indeed, there is the Zen of repetitive false casts in such a naturally beautiful environment — a divergence from the moments of panic when a striper scoots across a sand flat. It all comes together for me in the salt marsh’s moments of unique and attractive symmetry. The extension of floating line and the laying up of a foam popper against a lively grass-covered bank. The pop, pop, pop and the boil just behind. And finally, the thump as a striper comes tight. There’s nowhere I’d rather be at that moment.

Many anglers miss out, thinking that bigger water offers more action and a better opportunity for catching bigger fish. Sometimes this theory is accurate. However, the glassy water of a salt marsh makes it easy to see the slightest movement of both predator and prey. These quiet and beautiful bodies of water often offer the angling experience of a lifetime.

The Grass-Shrimp Hatch

It all tends to start with the simplest yet most abundant of Northeast salt marsh inhabitants: grass shrimp. Not only do they seem to be the most plentiful bait in New England and mid-Atlantic salt marshes, but they are generally the first to show. When a good hatch goes off, it can literally jump-start the striper season.

Because these tiny crustaceans feed on detritus, algae and dead plant material, they naturally exist in dense numbers in salt marsh environments. While there are a few different species of grass shrimp native to Northeast marshes, they all hold one trait in common; they flourish in the right circumstances.

Grass shrimp are very small, translucent critters — a quarter-inch to an inch. Yet when a grass-shrimp hatch goes off in a salt marsh, it’s usually quite an event. Thousands of these crustaceans populate a relatively small and shallow area. If it’s a big hatch, stripers lazily sip them up. You’ll see fish rolling, but you likely won’t see them crashing the surface. These first fish tend to be on the smaller side, ranging mostly from 20 to 26 inches, but it’s not uncommon to find a few larger ones in the mix.

The best place to target these early season stripers is the shallow, dark mud-bottom flats, as these areas tend to warm quickly when exposed to the sun. Because of the decaying grass and the resulting peat deposits, most mud flats in Northeast and mid-Atlantic marshes do in fact have dark bottom characteristics.

Such grass-shrimp hatches can sometimes be difficult to fish. “In most cases, you have so much small bait that it’s hard to get a striper to eat a fly,” notes eastern Long Island, New York, guide Capt. David Blinken. “The odds of getting a small grass-shrimp fly noticed among casually feeding stripers sucking down bunches of the real thing aren’t great.” Because of the nutrient-rich waters found in such salt marshes, you can expect murky water and poor visibility. I wouldn’t say that grass-shrimp flies don’t work here, but you have to be a good enough caster, or just lucky enough, to get one directly in front of a feeding striper.

Personally, I tend to do much better with foam poppers. Of course, they look and act nothing like the bait, but still they tend to trigger aggressive responses. I happen to believe that stripers, particularly those that prowl the marsh flats, are such aggressive creatures that if you pull something loud and obnoxious in their vicinity, they will instinctually take a whack at it. Mind you, I didn’t say they’ll eat it. With such small bait hatches in the marsh flats, I’ve found that when you use a popper, a striper will often boil on it, whack it with its tail and do just about everything but eat it. Sure, it’s fun to watch, but actually hooking a fish on a popper during a grass-shrimp hatch isn’t as simple as it seems, particularly if you are like most red-blooded anglers who want to set up on every single boil or tail slap. I’ve found that just leaving that fly dead in the water after a boil or whack will often cause the fish to think whatever it just whacked is stunned and then come back and try to eat it.

Grass-shrimp hatches are not just an early spring event. Really, grass shrimp can be numerous well into the summer months, but expect any feeding activity to become more of a nighttime deal once June arrives.

The Cinder-Worm Hatch

Speaking of nighttime hatches in the salt marsh, I’d be remiss if I didn’t cover cinder worms in some detail. Cinders are numerous 1- to 3-inch worms with an off-color head (usually olive) and a pinkish red body, although this can vary not only from region to region but also from salt pond to salt pond. When a hatch goes off, there are literally thousands of these things in the water, and stripers gorge.

These worms are mud burrowers for most of their lives. Hatches occur when cinder worms leave this safe environment. The phenomenon is not really a hatch at all; it’s actually a spawn. When the conditions line up, cinder worms go through a metamorphosis that includes the development of a paddle on their tail and the release of all but the segment of their body that contains the sex cells. At exactly the right moment, the worms in their new form travel to the surface, where they swarm in large concentrations, releasing their sperm and eggs in a reproductive frenzy that fly-fishers in-stinctually call a hatch.

Such swarms are a spring event in many regions and occur most often in the dead of night, with some exceptions in Rhode Island and Martha’s Vineyard salt marshes, where they are known to occur in the late afternoon. Cinder-worm spawns are very hard to predict. Conditions have to be perfect for a full-blown spawn to take place, and adding to the complexity, those conditions vary greatly from salt marsh to salt marsh. There are many variables, such as the moon phase and tidal ranges, weather and wind conditions, water temperature and air temperature, and current flow.

When you encounter a spawn, you will likely see stripers slurping worms all over the place, and many of them will be quite large. But getting them to eat, and particularly the larger fish, can be very difficult, if not seemingly impossible.

Stripers can get very, very finicky during cinder-worm spawns. Unlike during a grass-shrimp hatch, stripers won’t seem at all interested in poppers. It’s tough to imitate a 3-inch cinder worm and its erratic spawning movements. A lot of saltwater fly-fishers associate this occurrence with a freshwater bug hatch, as the surface activity, feeding habits and difficulty level are analogous.

There are a lot of cinder-worm patterns out there. Dixon’s Fireworm is one of the best, with its marabou tail and short, stout Lite-Brite body. It is pretty much a dead ringer for the worms in my neck of the woods. I primarily use a simple fly consisting of a 1/0 hook with an olive ICE Chenille head and a 2-inch red rabbit-strip tail. Jack Gartside created a Gurgler that makes a tremendous commotion on the surface but is just about the size and color of a cinder worm. This fly can be deadly, particularly when you can’t get stripers to eat anything else. Believe it or not, I’ve had quite a bit of success using a 4- to 6-inch black Deceiver, as I’m a firm believer that there are times when bigger is better.

Regarding where and when to look for such spawns in your local salt marsh, start with new and full moons. That’s not to say you will always find them, but these times are a good first bet, as there is a lot of theory out there that associates such spawns with warming mud bottoms. Undoubtedly, cinder worms gravitate toward light. “Cinders are photophilic,” notes fly-fishing teacher Mark Sedotti, “so dock lights draw numbers of them.” Sometimes the trick is to find such lighted areas around dark mud bottoms.

**

Marsh Menhaden

It’s pretty well accepted at this point that menhaden (aka bunker) are one of the most, if not the most, important food sources for striped bass. And during the early to mid-spring, bunker certainly take residence in salt marshes.

Because bunker are big bait, they tend to attract big stripers, and to catch the latter, you’ve got to throw big flies. Years ago, fly-fishers used to catch a lot of big bass by drifting 450- or 500-grain lines and wide-profile 9-inch flies under schools. That’s become quite a bit tougher these days, maybe because there are fewer stripers around or because it’s become quite hard to find bunker in a salt marsh without one or two boats throwing cast nets at them.

Still, there are times where you’ll get on pods of bunker in the salt marsh that are getting worked by scary-big stripers. And occasionally they will push that bait onto the marsh flats. That sort of thing generally happens in May, and when it does, it’s game on!

Menhaden found in most regions’ salt marshes stick around all the way through June and thin out considerably by July. In the later part of June, it gets much harder to entice a big striper with a fly.

At one point, once summer and September had rolled past, you could expect to see loads of young-of-the-year menhaden (aka peanut bunker) in the creeks and mud flats of most Northeast salt marshes. In late September and early October, these fish were around 3 inches and would begin to flood out of the creeks. When that happened, the marsh flats would come alive again with some extraordinary striper feeding frenzies.

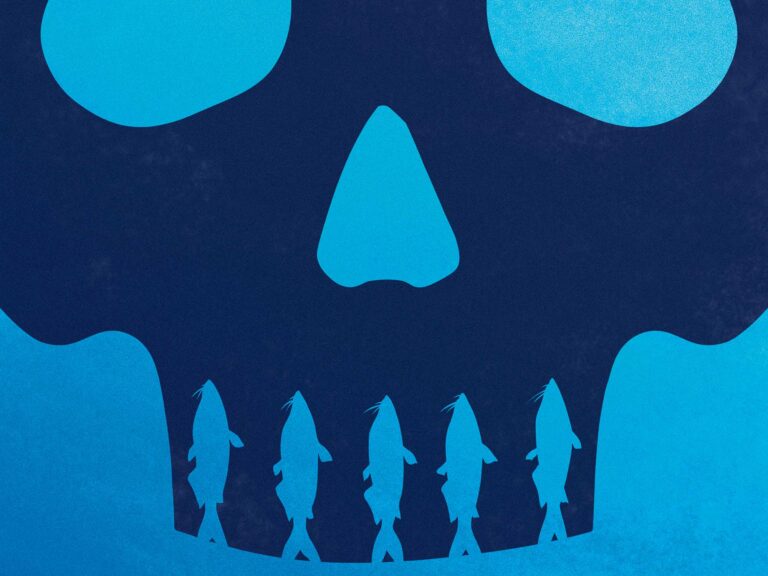

In recent years, this hasn’t come to pass. At first I assumed it was just a local issue, but the dearth of peanut bunker seems to extend across the coast’s salt marshes. It’s hard to say exactly what’s going on, as there’s still a sufficient amount of adult bunker around during the spring. Overfishing of the younger fish by the reduction fishery in Chesapeake Bay may be the culprit. Or perhaps it’s the large bait boats netting adults off the mid-Atlantic and New England coasts in the summer. Whatever the cause, the scarcity doesn’t bode well for the future of a very important baitfish.

Peanut bunker pretty much fueled a fall striper bite in the salt marshes. Without them, there simply isn’t a fishery back there. Sure, we get a week or two of pretty good action on silversides, but they don’t produce near the feeding frenzies that peanuts did. These days, most of the stripers stay on the outside and feed on sand eels. And while I’m grateful for those sand eels, stripers simply do not feed on them with reckless abandon like they do peanuts. Peanut bunker create epic fall blitzes, often within the confines of the salt marsh mud flats. I miss that, and I do hope one day it returns.

Summer Doldrums

With salt marshes, some anglers point to July and August as the summer doldrums. Because there isn’t much of a fast-moving current and the bulk of salt marshes are shallow, they warm to the point where it becomes uncomfortable for striped bass to remain. Furthermore, the nutrient-rich water in such estuaries tends to create overly large algae blooms that, by July, lower oxygen levels.

Thus, to some extent, the summer doldrums theory is true, and the quality stripers tend to be replaced by big, mean, toothy bluefish that prowl the marsh flats (and are fun in their own right). However, I’ve found that there are plenty of schoolie stripers around during the summer months, populating the winding network of shallow creeks that snake though the inside of the marsh. Such creeks usually hold an abundance of grass shrimp and small crabs. In the dawn hours at low tide, you can witness bass feeding in under a foot of water, rooting in the mud for small crabs while their tails flop on the surface.

While these fish are generally in the 14- to 24-inch range, with the occasional 28-inch fish in the mix, they can be an awful lot of fun on 6- and 7-weights. Any striper, no matter what size, will fight like the dickens when hooked in shallow water. I usually toss small Gartside Gurglers just for the vicious surface strikes they generate. Small chartreuse-and-white Clousers work well for these fish also.

Trip Planner

Rods/Reels: 6- through 9-weights matched to reels with quality drag systems.

Lines: For most situations, a clear intermediate line is all you need, but floating lines are useful for fishing poppers.

Leaders: Five feet of straight 20-pound fluorocarbon for poppers. For everything else, a 9-foot tapered leader.

Flies: Clousers, Half and Halfs, Dixon’s Fireworms, Gartside Gurglers, Deceivers.