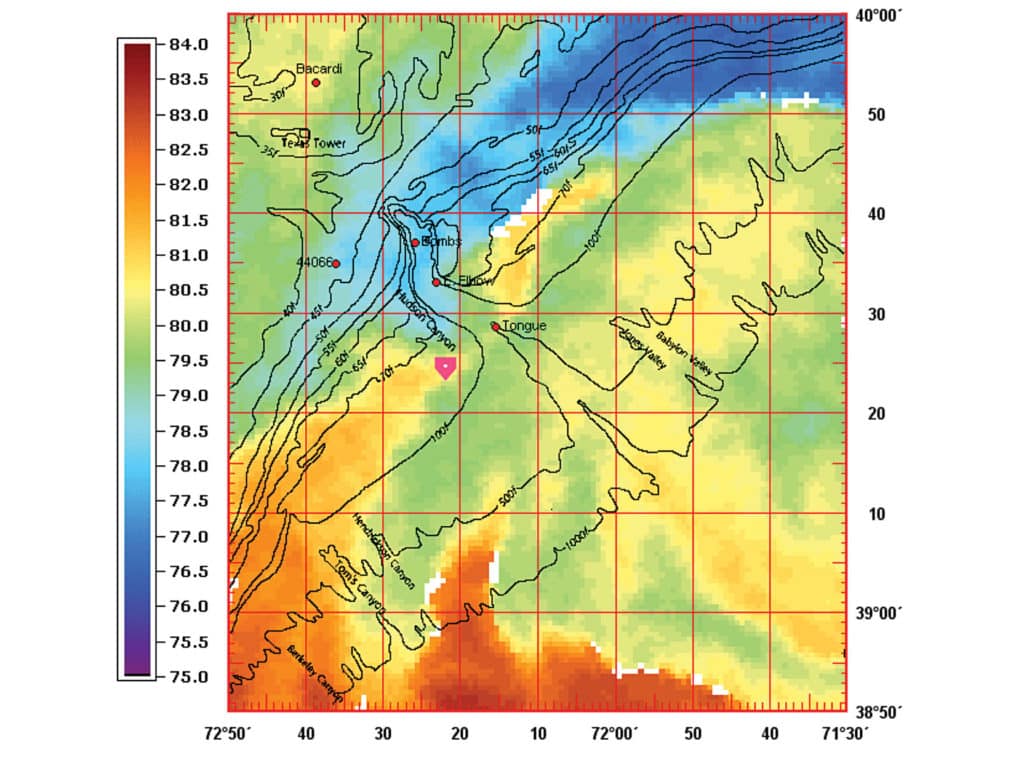

When the alarm goes off hours before sunrise, I roll over and grab my phone. The screen lights up with bright orange, red, blue and green swirls: a satellite image of the mid-Atlantic water temperatures. I note where the color change crosses the 100-fathom drop. That’s where I’ll be fishing today. Satellite images of water temperature, chlorophyll, altimetry and other data indicate the location of fish, making the pictures a powerful tool.

Ask the Expert

Dr. Mitch Roffer also begins his day looking at satellite images, trying to figure out where the fish will bite. The difference is, as president of Roffer’s Ocean Fishing Forecasting Service Inc., Roffer has a team of oceanographers and an array of resources to create fishing forecasts from Maine to Texas.

Roffer starts with images from a half-dozen satellites. Monitoring how bodies of water move over hours and days, the forecasters predict where the ideal conditions might occur.

Conditions beyond water temperature affect fish behavior, Roffer points out. Satellite images of chlorophyll concentrations indicate water clarity. “Where concentrations are lower, the water will be clearer,” he explains. Certain fish prefer a particular water clarity.

Weather also affects water conditions, but Roffer says it takes six to 12 hours for wind to have an effect. In the summer when the water is too warm, inshore anglers look for an offshore wind to bring cooler water to the surface near the beach. Rain or drought on land also impacts the water far offshore as it changes the atmospheric circulation.

The final step is noting how long the water conditions have remained in an area. “In general, the longer the favorable conditions persist in one spot, the better the fishing,” Roffer says.

Old Water, New Water

Capt. Jack Sprengle, who fishes inshore and offshore out of Rhode Island, relies on satellite data to direct his fishing. Sprengle looks for patterns in how the water is moving. In addition to temperature, he considers chlorophyll charts to find areas with clean water. “I’d rather fish old water than new water,” Sprengle says. A water body that has been stationed over an area for several days will aggregate bait and fish, whereas good water that is new to an area may not have had time to set up for the best fishing.

Good water will hold fish, even if the body is not associated with structure, and structure doesn’t always have to be on the bottom. “When warm, clear water moves inshore, we find dolphin and wahoo on the buoys of the shipping channel 30 miles from shore,” he says. The key is to find an area where good water has been stationary long enough to attract both bait and fish.

The Breaks

Along the mid-Atlantic coast, the Gulf Stream rushes up from the south to meet the Labrador Current cascading from the north. As these ocean currents meet, eddies of warm water break off and swirl along the 100-fathom line. Gulf Stream patterns change with the seasons, bringing a smorgasbord of offshore fish to the canyons and drops. Throughout the year, marlin, tuna, wahoo and dolphin ride those eddies like a superhighway. Smack in the middle of the road, Virginia Beach charter skipper Capt. Randy Butler uses satellite temperature data to plan his day.

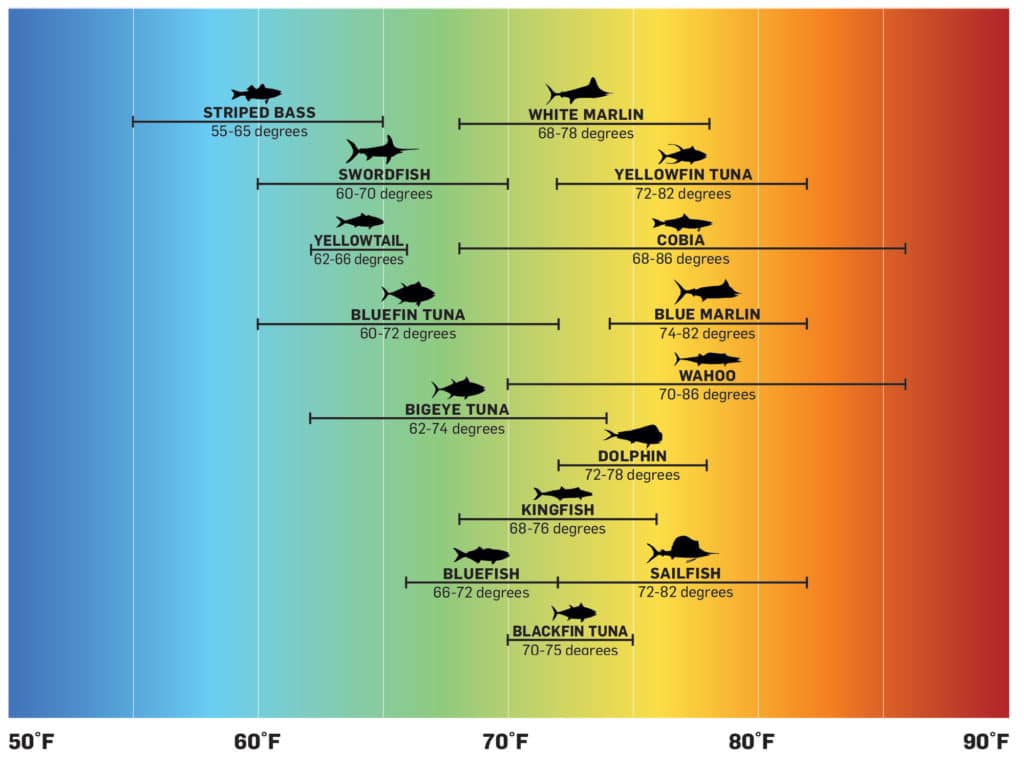

“Tuna fishing is good in the spring,” Butler says, “because 60-degree water butts up against 70-degree water.” The pattern repeats in the fall as inshore water cools. Finding the break on the satellite shot before he leaves the dock gives him a place to start, but tracking the break during the day keeps him on the fish. “I work with the other boats to map the break and follow it,” he explains. One day last spring, the break moved 15 miles east over six hours, Butler recalls. “We just followed it to stay on the fish.”

The break may not be associated with a color change and may only indicate a 1- or 2-degree temperature difference. That’s often the case in summer when white marlin congregate bait on structure around the canyons and seamounts. “A few degrees matter to marlin,” he says. Water clarity is also important when he looks for marlin. “Marlin like clean water,” he says, “so tracking the blue water is as important as water temperature.”

Plumes and Blooms

Algae are the biggest factor affecting water clarity. The fresh water from rivers and estuaries feeds algal blooms that cloud the water and turn it from blue to green. Anglers monitor algal concentration and water clarity with satellite images of chlorophyll concentrations.

“I check the water conditions first thing in the morning and check them again when I get home,” says Capt. Kevin Beach, who fishes out of Venice, Louisiana, at the mouth of the Mississippi River.

For marlin, he looks for clean, blue water. For tuna, the water has to be clear but not necessarily blue. “As long as the water is not cloudy, we catch tuna.” Blue water between 72 and 80 degrees is best for blue marlin. Beach admits that clear, green water still holds blue marlin. “You won’t get as many bites,” he says, “but green water holds the biggest blue marlin.”

“Water conditions can change in an hour,” he adds. The Mississippi plume often reaches as far as 80 miles offshore, or blows east or west with the wind. He looks for the color change to move quickly. “I’ve seen it move 20 miles in a day.” He likes a fast-moving change because it picks up grass and fish as it travels. “If the change is stationary for several days, it seems to lose fish.”

Just because he encounters darker water doesn’t mean he gives up on fishing. “Sometimes dirty water will be cooler, which attracts fish.” Other times, cooler, dirty water rolls over warmer, clear water. Beach recalls a similar scenario a few years ago. “We fished a rig in beautiful blue water that was covered with tuna and blue marlin.” The next day, he found the rig surrounded by dirty, brown water. Beach took a chance and deployed a rigged bonito. “The bait hadn’t been in the water 30 seconds when we hooked into a giant blue marlin,” he recalls. After releasing the first fish, they returned to the rig and hooked another big blue.

Inshore Applications

While offshore anglers rely on satellite resources to set their strategies, inshore anglers also benefit from this valuable information. Capt. Jim Ross covers the inshore waters of the central Florida coast, looking for cobia, tarpon, redfish and speckled trout. He says water temperature plays a critical role in finding fish. On the flats, a degree or two difference in water temperature congregates bait and fish. “In summer, cooler water holds more oxygen and fish,” Ross explains. He knows rainstorms cool the water, or he looks for fish in deeper areas. In winter, warm water is key. “The warmest water is on top of the flats or the lee of islands,” he says.

In nearshore waters, a coldwater upwelling produced by a strong offshore wind pushes bait and fish offshore. Ross looks for cobia in water from 68 to 72 degrees. Tarpon prefer it warmer. This past spring, he patrolled the Canaveral coast looking for cobia. “The water was cold and I wasn’t seeing fish,” he recalls. So he called Mitch Roffer, looking for an updated report. “Mitch told me I was sitting in a body of cold water,” he says, “so I ran 5 miles south where I found 72-degree water and cobia popping up on the surface.”

Getting Data

From raw satellite data to detailed, custom fishing forecasts, anglers have a wide variety of satellite resources for tracking water conditions.

Roffer’s Ocean Fishing Forecasting Service: various subscription plans

RU Cool (Rutgers University Coastal Ocean Observations Lab): free

Sirius XM Marine: $12.99 to $54.99 monthly

Terrafin Satellite Imaging: $99 for a full year

Fast Facts for Success

Highs and Lows: The differences in sea-surface height, called altimetry, indicate where one body of water pushes over another.

Baseline: Satellite images of chlorophyll concentrations indicate water clarity and nutrients that fuel the food chain.

Breakdown: Look for bait and predators wherever the water temperature or clarity changes drastically over structure.

Different species prefer particular temperature ranges. With this in mind, study recent SST charts, as well as previous images, to track trends and home in on areas most likely to hold fish during the season when they are available. This saves time and fuel, and eliminates random searching.