My son, Joshua, and I were outbound, cruising at 14 knots on a moonless night with the goal of arriving at the offshore fishing grounds at first light. Boat traffic was light, but we remained vigilant. Joshua was paying particular attention to a flickering green light about 2 miles to our port side. It appeared that we were passing it, but, moments later, the radar guard-zone alarm began squawking. A target had penetrated the half-mile perimeter and was closing fast; it was that green light. I pulled back the throttle just as a 20-foot center-console crossed no more than 100 feet in front of us doing about 24 knots.

That boat had no white light, and it never slowed down. We continued our night passage, shaken but thankful for marine radar and its guard zone. Today new radars offer collision-avoidance features that go far beyond guard zones. The latest innovations from Furuno, Garmin, Raymarine and Simrad help captains easily identify radar targets and better evaluate their threat potential in limited-visibility situations.

State of the Art

Advances in solid-state technology and processing have opened a new world of features and versatility while also making these marine radar systems easier to use and interpret. This heralds the eventual extinction of power-hungry magnetron-based radar antennas, as solid-state radar antennas consume less energy, last longer, and, most important, offer better control over signal transmission and processing.

“The new radars also start up much faster,” says Jim McGowan, marketing manager for Raymarine. “A magnetron requires 90 to 120 seconds to warm up,” McGowan points out. “A solid-state system, such as Raymarine’s new Quantum CHIRP dome radar, is ready in 10 seconds from a cold start.” This means your radar is looking for targets instantly.

Better Definition

Solid-state technology makes possible a feature called pulse compression. This differs significantly from the single frequency pulse transmitted by a magnetron. Raymarine uses the term CHIRP (compressed high-intensity radar pulse), an acronym more closely associated with today’s advanced sonar systems, to describe its pulse compression capabilities.

With such technology, a long pulse transmits over a wide range of frequencies. By processing the relative strength of the returning frequencies, the radar can more accurately gauge the size of targets and gaps in between, as well as their distances.

How does this help you? Say you’re returning to port in a fog after a day of fishing, and there’s a boat between you and a navigation buoy. A magnetron radar might display both things as one object — a misleading return that could result in a hazardous situation. Pulse compression will show these as two distinct targets, so you navigate the channel more safely.

Long and Short of It

Pulse compression gives you the best of both long- and short-range target detection. Simrad’s solid-state Halo series of open-array radars, for example, combines the ability to see well-defined targets as close as 20 feet while also offering excellent long-range performance. The top-of-the-line Halo 6 boasts a 72-nautical-mile range.

The same kind of short- and long-range benefits are available in Garmin’s new solid-state Fantom series of open-array marine radars. Furuno’s new DRS4D-NXT and Raymarine’s Quantum dome radars also combine short- and long-range target detection, but they are limited to 48 and 24 nautical miles, respectively, on their outer ranges.

On the Furuno, Garmin and Simrad systems, you can view two range scales at once and monitor targets of immediate concern while also keeping an eye on distant returns, including weather cells.

Narrow Thinking

Solid-state technology allows you to boost the definition of targets by sharpening the beam width. With Furuno’s DRS4D-NXT dome radar, for instance, set RezBoost to the maximum setting, and the beam angle of the pulse narrows to 2 degrees, creating return images as sharp as those of an open-array antenna.

Simrad uses a similar function called Beam Sharpening to give models such as the Halo 6 (with a 6-foot open array) the same target resolution as a radar with an 8-foot antenna array. A narrower beam angle can be particularly helpful when looking for flocks of birds or navigating a string of channel markers at night.

Doppler Effect

One of the most significant developments in solid-state technology is the advent of Doppler capabilities, now available in the Furuno DRS4D-NXT and Garmin Fantom series.

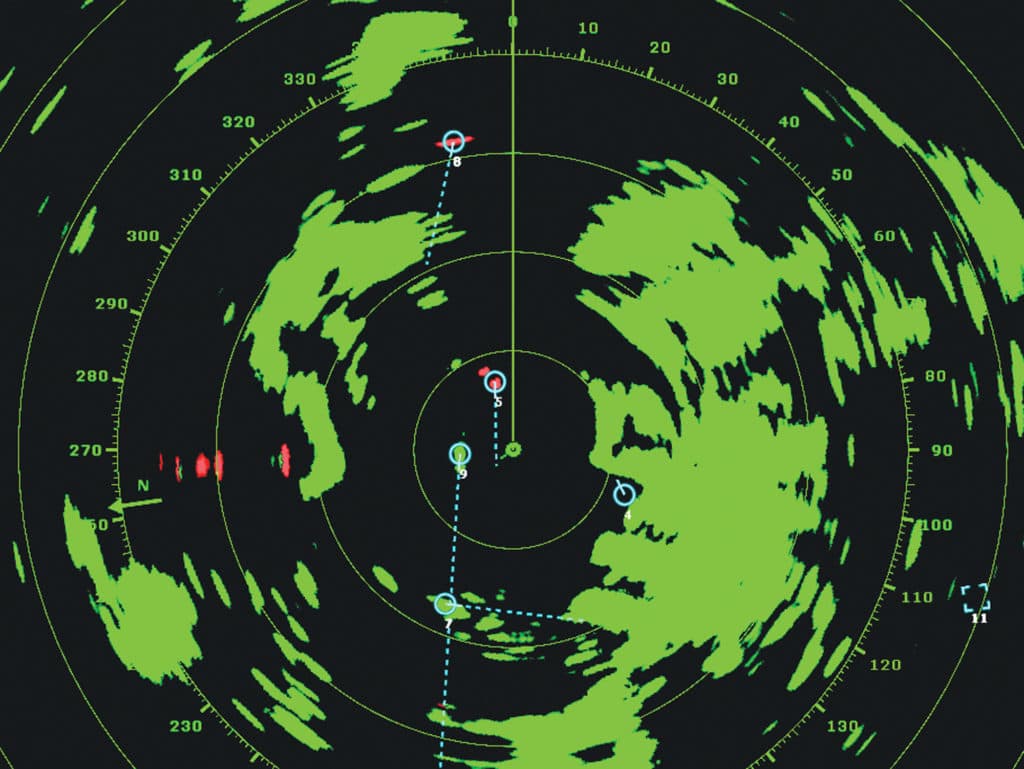

Furuno’s Doppler system, known as Target Analyzer, automatically changes a target’s color depending on the threat level. Anything stationary or moving away from the boat is green. Targets moving toward your boat at 3 knots or more become red. “With the radar’s ARPA (automatic radar plotting aid) on, the red targets also get an echo trail, and an audible alarm is sounded,” says Eric Kunz, senior product manager for Furuno USA. “There’s no need to set an acquisition zone; the ARPA automatically shows the vector, closest point of approach, and time to closest point of approach.”

The Doppler system from Garmin, called MotionScope, works in the same manner, highlighting targets moving toward you to easily identify and track objects that could pose a risk. Doppler measures the dynamic frequency shift of radar returns. Think of the difference in the sound of a siren on a fire truck speeding toward you, then away. The processor senses that difference to highlight approaching targets.

Thanks to solid-state technology, microprocessors and advances in software, marine radar is now simpler and more precise, enabling boating anglers to easily avoid potential dangers at night or in a fog.