It was one of fall’s first cold days. The wind cranked out of the northeast, pushing up whitecaps on the bay. I was beginning to think taking the skiff out had been a bad idea when I saw a cloud of birds working right up against the sod bank.

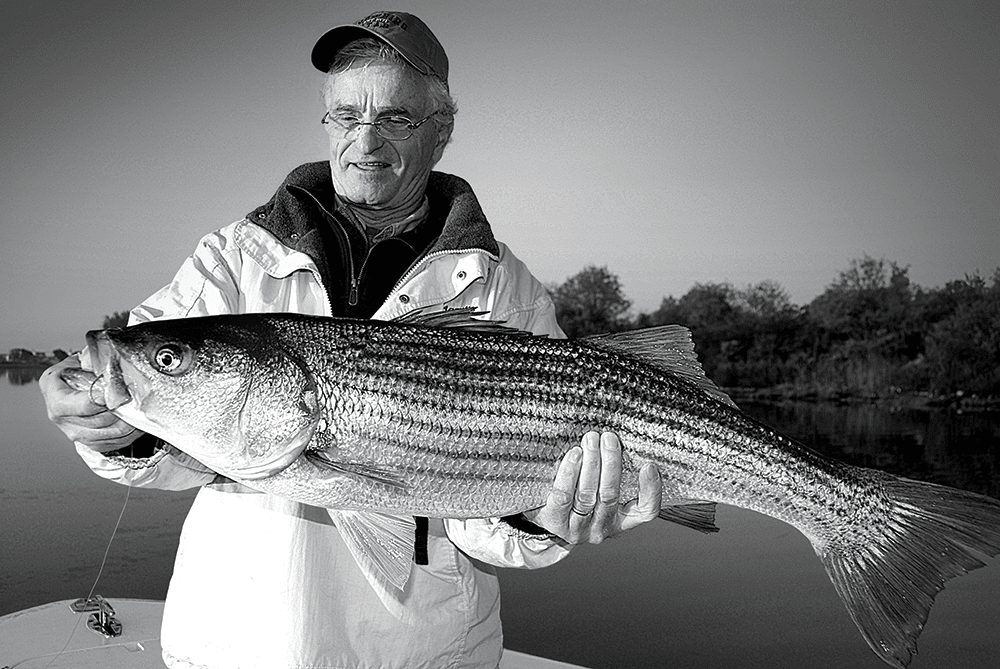

I killed the engine upwind from the bird activity and drifted down into it. Soon, big stripers boiled all around us, and silver-dollar-size baitfish sprang out of the water, attempting to evade the large vacuum-cleaner mouths. Suddenly, two poppers whipped past my head without warning. One barely hit the surface before it disappeared into a hole in the water. A 20-pound fish leapt out to grab the other.

A good seven or eight years had passed since I had last seen such a thing. The fishing in the back bays had been practically dead more autumns than I cared to recall. Bass were around, but they were on sand eels, which rarely venture into the bays in fall. Gone were the days of saving fuel, fishing five minutes from my marina. Or were they? The scene I just witnessed sure seemed like the good old days.

Baitfish-Driven Fishery

The truth is, in much of the Northeast, a great fall bay fishery depends on the schools of juvenile menhaden we call peanut bunker. These baitfish actually let us know if we are going to have a good fall run or not. When we start seeing the tiny ones swarming at the marina or in the shallow-water creeks and mud flats around late July or early August, it’s good cause for optimism.

By late August or early September, the menhaden reach a couple of inches in length, and snapper blues feast on them. Then the masses of surviving baitfish start migrating out of those shallow spots, moving into the channels and bays. Come October, they have grown to 4 or 5 inches; when the water cools down, the striped bass get fired up and seem to instinctively know where to find the peanut bunker: inside the bays.

As the bait moves, the stripers lose their minds and embark on one feeding frenzy after another. The fishing, of course, is nothing short of spectacular, but perhaps the best part is that all this generally takes place in protected water. That means many more fishable days than if the fish stayed out in the open, for the weather in October and November is nasty more often than not.

Sand Eels vs. Peanut****s

“Nature abhors a vacuum,” said Aristotle, meaning that voids are quickly filled. Indeed, that phrase seems to apply to the marine environment in many cases. During the seven or eight years when juvenile menhaden numbers were low, vast schools of sand eels came inshore. Rarely, if ever, did we find large concentrations of both.

Sand eels are great. Without them, we probably wouldn’t have had a fall run all those years the peanut bunker were scarce. However, they just don’t spark that ferocity stripers and bluefish exhibit when they are feeding on peanuts. I don’t know why, but something about juvenile menhaden makes the fish go nuts.

Trying to fool a striper into eating a lure when sand eels are prevalent presents a greater degree of difficulty. It could be harder to faithfully imitate their slim profile and undulating movement, or it could be that sand eels don’t gather in schools as dense as peanut bunkers, but they don’t get predators quite as excited. Really, I think the answer is simple — stripers just prefer peanuts.

Effective Imitations

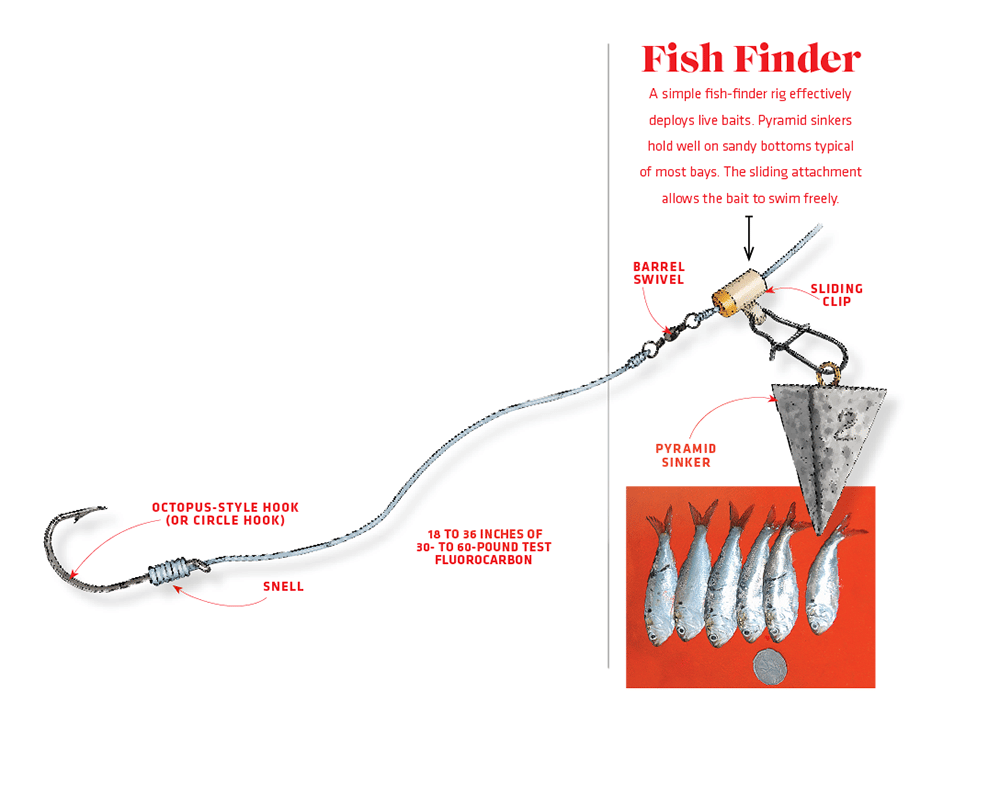

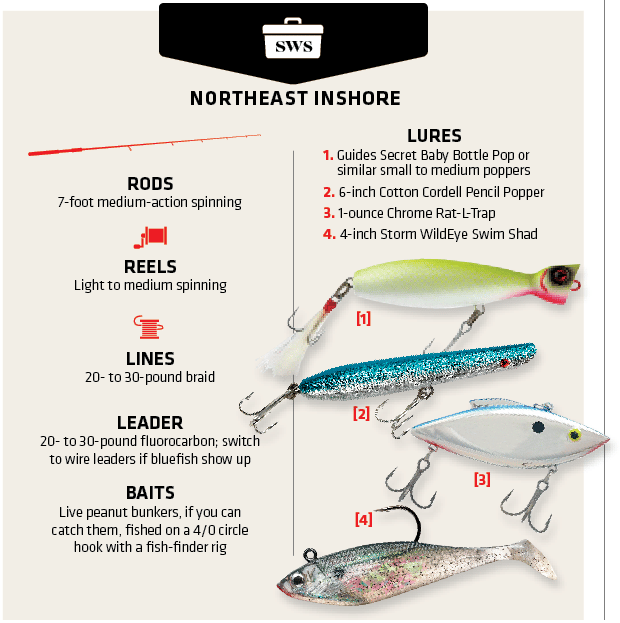

The fish get really fired up when the peanuts are around, and they aren’t terribly picky eaters then. That said, you should still make an attempt to match the hatch to increase your chances. That means using any artificial with the size and profile of the bunker.

Chrome Rat-L-Traps work well. Not only do they closely resemble the size and shape of a peanut bunker, they also have the same erratic swimming action. The built-in rattling only makes them more noticeable. Storm’s WildEye Swim Shad in bunker color is another dead ringer for peanut bunkers.

When the fish blitz on the surface, like they often do, I opt for poppers. I’m a big fan of those savage, heart-stopping surface strikes. Honestly, it doesn’t matter too much which poppers you choose, but I really like the Guides Secret Baby Bottle Pop. It’s nice and small — about the same size as a peanut bunker — yet it’s relatively heavy, so you can cast it pretty darn far. That thing pushes a lot of water on the retrieve and makes a ton of noise. If you work it slow and steady, it acts like a swimming plug. And for the times when the fish seem a little less aggressive, I like the 6-inch Cotton Cordell Pencil Poppers. These lures imitate a wounded bunker well.

Puzzling Hiatus

Back in 2006, I thought the absence of peanut bunker might have been limited to lower New York Harbor and Jamaica Bay, but as time went on, it became apparent to me that this was a regional dearth that extended well beyond my local waters.

Overfishing of the juvenile menhaden didn’t seem to be the culprit; the years when peanuts were MIA, we had some of the densest concentrations of adult menhaden during spring and early summer.

Since menhaden spawn at sea, the lack of juveniles in our bays could have been the result of a combination of oceanic factors. It’s not illogical to think the reasons were climate related. In fact, NOAA Fisheries stated on its website that “menhaden recruitment appears to be independent of fishing mortality and spawning-stock biomass, indicating environmental factors may be the defining factor in the production of good year classes.”

We could continue to speculate as to the reason, but the bottom line is that no one knows why the peanuts failed to come into the bays for several years. But something must have happened in 2012 because extraordinary concentrations of peanuts showed up from late August to October 28, the day superstorm Sandy hit. Last year, the numbers were pretty good also, so I’m hopeful we’ll have more of the same this year and the trend will continue.