Great fishing for white seabass off Southern California’s coast in recent years seemed to confirm the positive impact of an intense stocking program underway since the early 1980s.

But, as the saying goes, something didn’t compute.

All of the 2.5 million juvenile sea bass originating from the Hubbs-SeaWorld Research Institute hatchery were implanted with coded wire tags. However, even as fishing improved, scientists found that just a tiny percentage of harvested fish were confirmed to be carrying the tags.

The preliminary results of a recently released study seem to have solved part of the mystery, while leaving scientists contemplating another.

It’s In Their DNA

Researchers from HSWRI and the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources (SCDNR) led a study by Ellen Reiber, a graduate student at the College of Charleston who looked at genetic markers to determine the origin of collected seabass. Reiber found that an astounding 46.2 percent of juvenile fish originated from the hatchery. By comparison, only 7.4 percent were found to be carrying coded wire tags, tiny pieces of etched metal that are found using a metal detector.

The massive disparity indicates the fish either shed their tags or the tags were not being detected as the fish were examined.

“It’s just fascinating to me that these coded wire tags are not working as well as we thought,” said Mark Drawbridge, senior research scientist at HSWRI. “When we got the results back I was shocked, but I was shocked in a good way.”

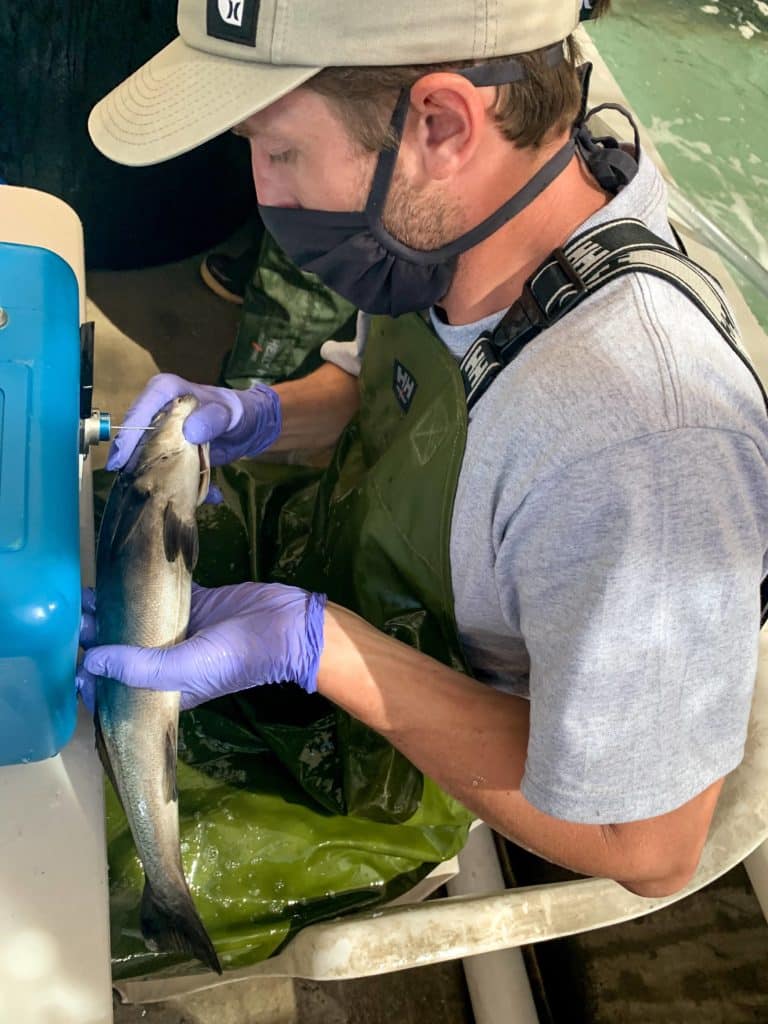

Reiber studied genetic markers in approximately 700 sub-legal-sized white seabass collected from the Oceanside, San Diego and Newport Beach coastal areas since the mid-1990s, comparing the information to the genetics from hatchery broodstock. The genetic information was from DNA in the otoliths (tiny bones found in a fish’s inner ear) that had been collected and stored.

Drawbridge said the method is incredibly accurate and SCDNR has been using it on other species for many years.

“With the genetic marker they have developed, if they say it’s a hatchery fish, there is a 99.999 percent confidence level,” he said. “It’s basically a 100 percent certainty.”

A separate analysis in this study looked at 50 adult white seabass caught commercially in Mexico. No coded wire tags were found in any of the fish, but the genetic study showed that nearly a third of the fish were from the California hatchery.

California’s Ocean Resources Enhancement and Hatchery Program was launched to help determine the feasibility of using hatchery stock to improve populations of finfish and to assess the biological and economic impacts of such programs. White seabass became the primary focus of the program because of the combination of their importance to recreational and commercial fishing along with the depressed state of their population.

Originating at the Hubbs-SeaWorld hatchery, white seabass fingerlings are farmed out to one of nine acclimation pens once they reach about 4 inches in length. Volunteers from the Coastal Conservation Association care for and feed the fish before they are released after reaching a length of about 10 inches.

Fees from validation stamps required of anglers who fish south of Point Arguello, along with Federal Sportfish Restoration Act funds, cover the cost of the program.

Further Study Needed

Drawbridge said the next step for researchers is to increase the sample size of legal-sized fish and also to try to determine what happened to the coded wire tags, which are implanted in the cheek muscle of the fish.

Did the fish shed the tags? Did the tags move to a different part of the fish? Something else?

That work will likely involve x-raying the heads of seabass, another unique step in what continues to be a fascinating story.

“Because coded wire tags are used in many species around the world, the implications of this part of the story are potentially of great magnitude,” Drawbridge said. “Stay tuned.”