I vividly remember visiting the Florida Keys as a kid in the 1970s. Coming from Ontario, Canada, we were escaping the cold and experiencing things that we didn’t have on the Great Lakes. This was a time when local conch was still on the menu, as was all-you-can-eat shrimp fresh from the Gulf.

Once, I asked my parents to stop at a marina in Islamorada after the charter boats docked, not to see grouper or snapper, but to get up close with sharks. Up until that point, I had only seen sharks on The Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau or National Geographic. What was different on that day in Islamorada was that all the sharks were dead, hung up by their tails. The heads of the large tigers and great hammerheads rested on the ground, teeth exposed. It is a moment still etched into my memory.

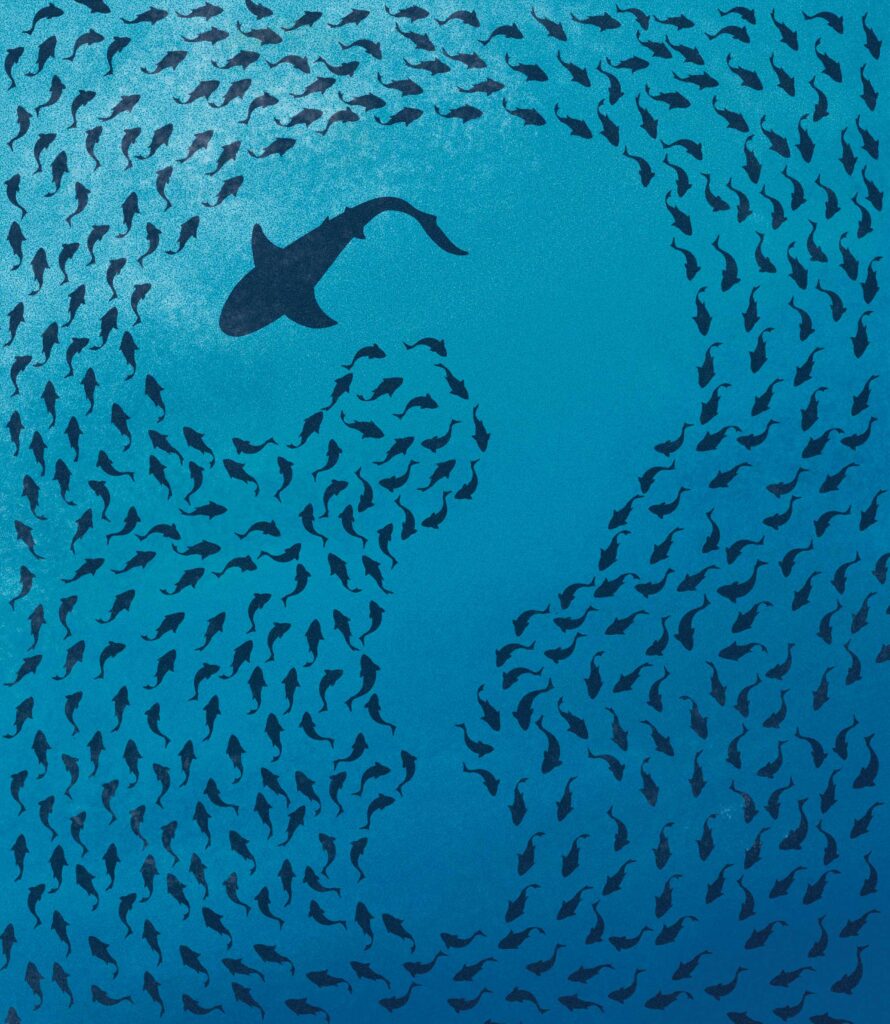

Fast-forward a few decades to my days as an undergrad, when I started to learn about the connections between fish species and the habitats they depend on. A classic textbook example was an ocean food web with an image of a shark on top. The accompanying narrative explained the role of apex predators helping structure and maintaining a healthy ecosystem. This was also a time when pressures put on ocean ecosystems were accelerating. Our ocean environment was feeling “the weight of humanity,” said Sandy Moret, famed tarpon angler in the Florida Keys.

By the late 1990s, commercial interests overharvested sharks to the point that many species were considered vulnerable, threatened, and even critically endangered. The mainstream media covered the practice of shark finning. We were facing a reality that without sharks, our ocean ecosystems would become terribly out of balance.

National and international shark conservation kicked into gear. After 30 years of efforts, there has been progress, but many species are just starting to recover. Globally, most shark populations are still in decline.

Now for the wicked problem. With populations rebuilding for some shark species, anglers are increasingly reporting losing hooked fish to sharks. These encounters are known as depredation. There are also more anglers fishing in our coastal waters than ever before, contributing to increased encounters with sharks. Fishing is popular, and anglers have every right to go fishing. In fact, anglers are important eyes on the water in the fight for conservation. Yet, when a shark takes a prize fish off your line, it can really piss you off. For fish we release, predation can also happen after they swim away.

Is it a shark problem? My lab at UMass has been studying depredation and post-release mortality in recreational fisheries for many years. Tensions between anglers and sharks only continue to grow. There are other predators too, such as sea lions in Pacific waters. Similar to my vivid memory as a kid in the Keys, I remember like it was yesterday when I watched a massive great hammerhead shark chase down a tarpon under the Bahia Honda Bridge. This all happened while we tried to land a tarpon to implant acoustic tags to study their movements and migrations. After chatting with fishing guides and anglers in the area, we embarked on a study to look at what was increasing the chances of a hooked tarpon being whacked by a great hammerhead.

Read Next: Are Mako Sharks Dangerous?

We found that it all came down to fight time and tide. The longer an angler fought a tarpon on the line, the greater the chances of depredation. There was also overlap in the habitats used by tarpon and great hammerheads on the outgoing tide, not to mention increased overlap where anglers were hooking and fighting the fish.

Who doesn’t like the fight of a fish on rod and reel? But for those pods of tarpon aggregating under the bridge prior to spawning, a lengthy fight sometimes was a death sentence. And losing those spawners negatively affects the next generation of tarpon. There is a quick solution to the first part of this problem: Fight tarpon harder, and get ’em landed and released in under 10 minutes. Of course, a shark could still go after it once released, but at least the fish has a fighting chance of survival.

Over the last five years, accounts of depredation from sharks have increased dramatically on the internet and social media. My lab recently conducted a survey of anglers that fish between North Carolina and Maine. Preliminary results show that it’s not just sharks, but also seals and seabirds swiping anglers’ catches. There is a lot of anger and dismay from depredation, plus safety concerns when reaching down to the water to land a fish.

Recently, the House of Representatives passed the SHARKED Act as a means to allocate federal funds to find solutions to this problem. We need fishing as a popular leisure activity that fuels passions and supports the economy. We also need sharks and other predators that contribute to the health of coastal ecosystems. There is so much more to be done to see if this wicked problem can be solved.