Fighting fish is far more complicated than just pulling on the rod and turning the handle on the reel. As saltwater anglers, we are challenged by incredibly powerful fish that test every aspect of our strength, endurance and gear. The best fishermen study and perfect fish-fighting techniques not because it helps them land fish more easily—though it does—but rather because it’s crucial for landing trophies.

Why? Because the faster you can land it, the better the chances a “fish of a lifetime” will stay on the line. Plus, being swift in your fight gives you more energy to fish longer. And that next fish could be even bigger, so you don’t want to be tapped out.

Many anglers fight fish inefficiently, making mistakes that cost energy, time and, ultimately, the fish. There are many factors that go into the fight, but one of the most important is using the power of your rod to your advantage. Many anglers think more about how their rod casts, or how sensitive and light it is, without understanding how to most effectively use it during the fight. Spoiler alert: It’s more complicated than pumping and reeling.

Action and Power

Unlocking your rod’s power requires understanding where and how it stores energy. Two rods identical in weight, length and lure rating can behave very differently from cast to landing. The differences are often due to the action of the rod, which has a large impact on its behavior during the fight.

To illustrate this point, imagine two rods, one fast action and one moderate, that produce 10 pounds of pull at maximum bend. If you try to lift 11 pounds with either one, it will simply break. The fast-action rod looks like a hooked-cane when fully loaded, focusing all 10 pounds of pressure in a small arc at the end of the rod. In contrast, the moderate one appears more like a rainbow, bending throughout the length of the blank.

Because of the tight arc, a fast-action rod has a relatively small sweet spot and can unload quickly during a fight. This means that with just a minor dip, all that stored energy—all that pull—is lost. This transfers a lot of strain onto the angler. Further, if a fish surges or the boat moves unexpectedly, the rod loads up extremely fast, providing limited shock absorption.

Now compare this to a moderate-action rod. It will distribute that 10 pounds of pull throughout 60 percent of the blank, instead of just at the tip. If the fish comes toward you or takes off on a run, the moderate rod is more forgiving because it can absorb the motion without over- or underloading. In essence, the uniform pressure throughout the fight makes it a better shock absorber. This can result in landing the fish faster, or even landing the fish at all. It’s the same power as the fast-action rod, just easier to use.

But everything comes at a cost. Moderate rods, in general, do not cast aerodynamic lures as well as faster-action rods. They are also typically heavier and less sensitive due to different blank materials. Further, hook-sets require more motion and energy, and take more initial energy to load up.

So, while that moderate rod might be powerful and forgiving during the fight, the fast-action rod is likely more sensitive, better-casting and lighter. What’s most important comes down to your species of choice, tactics and general preference. You need to know how to properly load your rod and what its limits are so you can use it to your greatest advantage.

Power Down Low

No matter how the rod bends, though, the tip is not for fighting fish; it’s for casting and sensing what is happening at the end of your line. Eliminating the tip and upper sections during the fight will produce far more pull on the fish. To do this, you must lower the tip of the rod enough so that the majority of the bend, or the load, is in the lower portions of the blank.

This is a concept many anglers do not understand, and it often makes them uncomfortable. You’ll hear fishermen say you need to “keep your tip up,” but this can lead to poor fish-fighting behavior. A high tip means you can’t load the deeper, more powerful parts of the blank, and you are also at risk of overloading and snapping off the tip. A best bet is to keep the rod angle between 30 and 45 degrees, depending on the action of the rod.

The more moderate the action, the more of the rod that will point directly at the fish and virtually parallel with the water; this is particularly true with light-action and fly rods. If you’re used to fighting fish with your rod up high, it’s going to feel unnatural at first, but you’ll get used to it with practice. It’ll mean less strain on your body, faster landings, and more room for mistakes.

Read Next: Rod Maintenance Tips

Locked and Loaded

Another mistake anglers make is repeatedly unloading their rod. At the hook-set and in the early parts of the fight, you must initially load up the rod. This means energy is going into the bend but not actually pulling on the fish, so you only want to do it once.

Tired, lazy or novice anglers will often let the rod sag and lose the bend. Then, as they begin to reel again, they will pull up on the rod, reloading it for a period before dropping it again, and repeating this over and over during the battle. I’ve got bad news: If this is you, you’re just wasting tons of energy that the fish isn’t even feeling. An unloaded rod is a rest for the fish, not for you.

Instead, get the rod to the proper bend and lock it there. You want to have significant load in the rod, but not so much that it’s completely tapped out, and a sudden movement yanks out the hook, snaps the line, or pulls you off your feet. Going the other way, not putting enough load into the blank means you’re missing out on power that can be used to land the fish more quickly, and slack can also form, resulting in a lost fish. Do everything you can to keep it in the Goldilocks position: not too much, not too little, just right.

Easy on the Pump

When anglers try to maximize their fighting power, they often resort to pumping the rod. This looks impressive on social media, but it’s not the best way to fight fish. Hard pumping is just a lot of wasted energy; you’re over- and underloading the blank repeatedly, risking damage to the rod, line, leader and hook. And it can enlarge the hole the hook made.

Further, if you’re aggressively pumping the rod and getting the tip up high, you’re relying on the tip to fight the fish and provide the shock absorption—a really bad idea. The rod is not properly loaded in the high and low positions of the pump, and it’s hard to react to the fish.

Remember, a properly loaded rod puts consistent pressure on the fish, decreases angler effort, and prevents break-offs due to sudden movements. For this reason, unlocking your rod’s power is done with a steady, consistent application of pressure. My philosophy is to load it up, lock it in, and leave it there. I try to load up the rod once, keep the tip relatively low, and rely as much as I can on my reel’s cranking power.

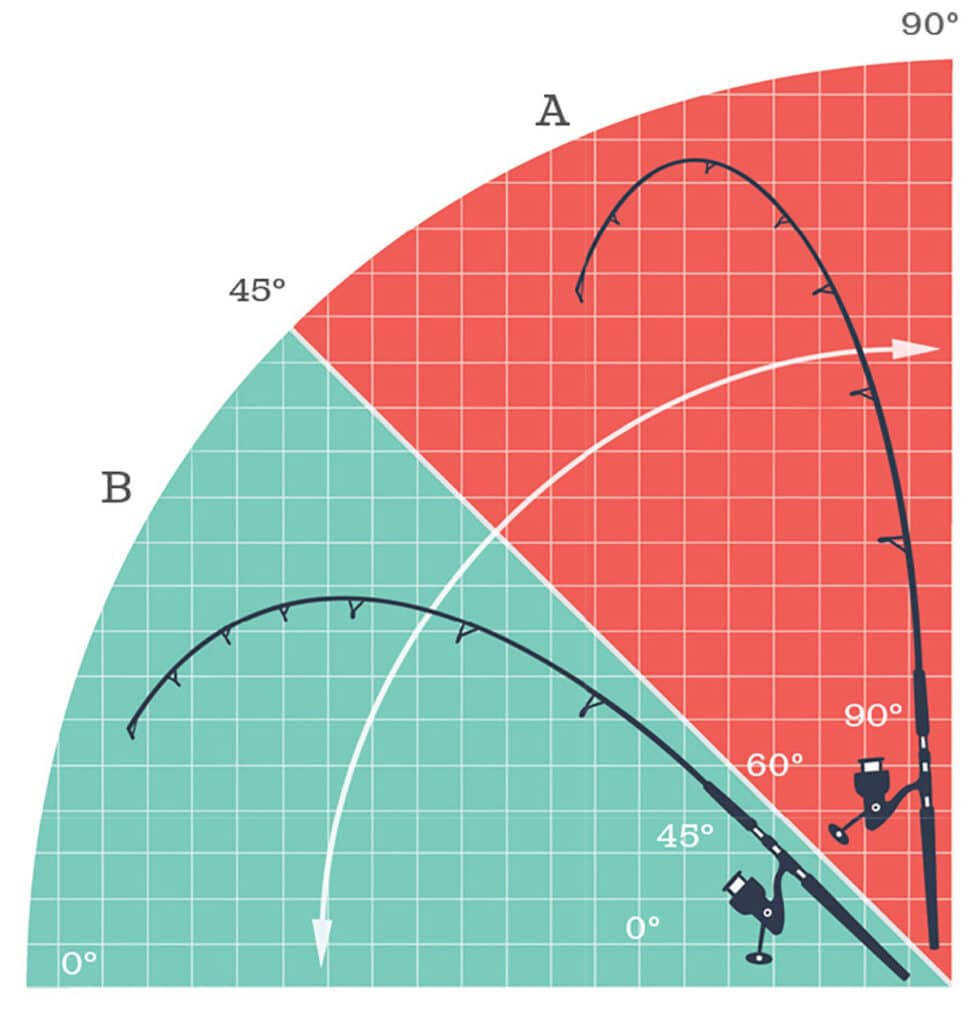

But I’m no Hulk, so I often have to employ small, steady movements to gain ground against trophy-size fish. I do this by raising and dropping my rod slowly in a 15- to 20-degree arc as I crank—not the fast, jarring 60-degree pulls that many anglers employ while pumping. Pumping the rod up and down dramatically is all for show—a rookie move. I’ll let photos of my catch show off for me.

At the Angle

Finally, once locked and loaded, getting the most power from your rod requires pulling on the fish from the right angle. While this is primarily important for boat anglers—especially fly guys—it can also make a big difference if you’re up high on a jetty or pier. This takes a little practice, but it can result in much faster landings. All fish, from 1 to 1,000 pounds, have an advantage if they’re heading away from you. Turn their head and you can land them more quickly; it’s as simple as that.

Imagine standing on the port side, and the fish is running toward the bow, moving left to right in front of you. Instead of turning toward the bow and pulling up on it, turn the rod sideways in your hand so the bend is parallel with the water, and the tip and line are heading directly toward the fish.

Now pull back on the fish, moving the rod toward the stern, not the sky. You’re now pulling directly back on the fish, not just up on it. If it keeps running straight, you’ve got the best angle to stop it in its tracks. But if it dives, you can quickly return the rod to the regular angle—straight up and down—and resume cranking. Just no pumping!

Rod Power and Conservation

Every fish you hook is fighting for its life. Even if you release it quickly, and even if you never remove it from the water, there is significant stress on the animal. While the fish might swim away rapidly and seem totally fine, a prolonged fight can cause permanent damage you never see. The fish can die out of sight, hours or days later, or get attacked and eaten by a larger fish, shark or mammal, such as a seal. In the end, choosing gear with enough power and fighting fish as efficiently as possible is a critical component of limiting this risk.

The species you target and the conditions should weigh heavily on your choices. Some species are extremely susceptible to release mortality, like bonefish, while others are very hardy. Temperature is a huge risk factor, as is the spawn stage the fish is currently in. Warmer water contains less oxygen, and high water temps can lead to dangerous levels of hypoxia and tissue damage during a long fight. Very low temperatures are also a risk, where the fish can go into shock during or after the landing. Finally, if you injure a fish pre-spawn or while it’s attempting to spawn, it might not reproduce. And post-spawn fish are often exhausted and susceptible to injury.

If you are a conservation-minded angler, choose heavier gear when in doubt. To be the best steward of your fishery, choose a rod, reel and line that can quickly subdue the largest fish you are likely to encounter. You don’t have to plan for a world record, but if you’re concerned about a fish’s release health, choosing gear for the more exceptional fish, not the average, is paramount. Yes, smaller fish won’t be quite as much fun, but that’s the trade-off one must make if you are serious about releasing your fish healthy and passing on angling to the next generation.