The action certainly wasn’t fast, but Andy Newman, Michael Ferrari and I had trolled up two schoolie mahi, plenty of meat for dinner. The scattered weeds, flying-fish showers, solid current and strong plankton front near Islamorada’s 409 Hump convinced me to stay despite the urge to start running-and-gunning.

Watching boats troll for a bit and leave, and others never slowing at all on their race toward the horizon, I still believed this area looked promising. As foresight would have it, we capped off our half-day of fishing with a mahi doubleheader, one of which was a trophy-class bull dolphin. Trolling paid off.

The No-Patience Generation

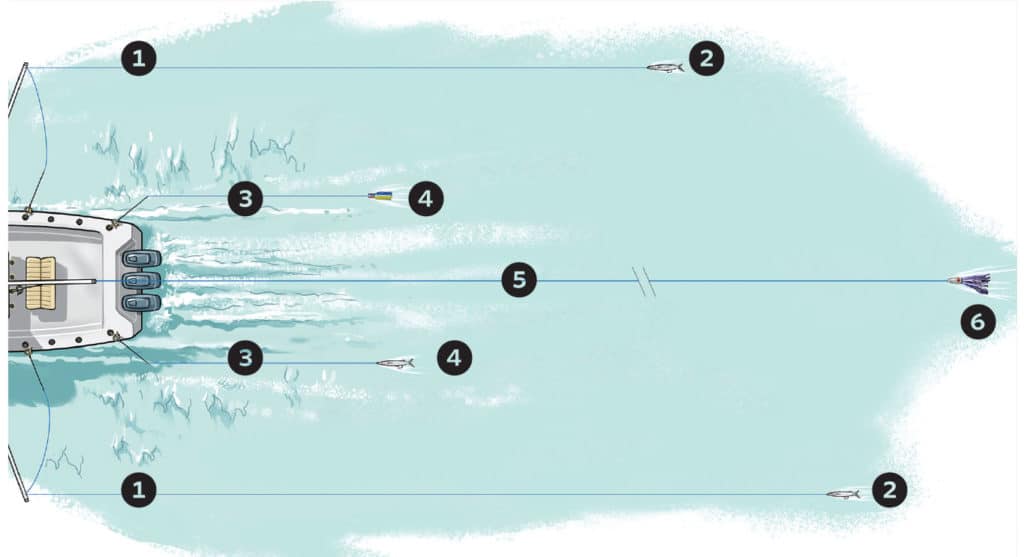

High-horsepower twin-, triple- and quad-powered center-consoles have created a lot of impatient anglers. If an area doesn’t produce in quick order, many crews will throttle down to look for the next one. But there’s no guarantee the next spot will be any better. Setting a full trolling spread and thoroughly working what might be a productive section of ocean is almost a lost art. Offshore fishing has become a game of instant gratification for some.

Impatient fishing is arguably most prominent off southern Florida, the Florida Keys, and even the Bahamas, where deep water exists relatively close to shore. It’s a bit different for offshore anglers in the Gulf of Mexico and canyon runners in the mid-Atlantic and Northeast, where long hauls are the norm—trolling here is still a mainstay practice. However, the mentality is spreading to these waters as well because fast boats can quickly traverse between canyons, bottom structures, surface-temperature breaks and eddies.

Running-and-gunning and even spot trolling (deploying a pair of flat lines for a limited time) are highly effective around working birds, debris and large weed patches. But if the fast-paced effort comes up empty at day’s end, your wallet and ego will both be crushed.

Slower Boats Catch Too

Capt. Glen Miller (gonfishinv.com) has been running the Islamorada, Florida Keys charter boat Gon Fishin V, a 10- to 12-knot vessel, since 1996. A top producer for his customers, I asked him how he competes against all the high-speed, outboard-powered boats.

“A lot of them simply overrun the fish,” Miller quipped. “Based on the current coming close in, a lot of our mahi catches are inside of 12 miles. Sometimes there are no birds to give them up. Guys running offshore miss the inside stuff. ”

Miller wants his lines in the water quickly after clearing the reef. “Our mate typically puts a tuna feather on an outrigger rod and one on a flat line,” says Miller. “Bonito catches are common between 50 and 200 feet, and beyond that it’s skipjacks and blackfins. Those bonito are important to us later on for mahi as chunks for school fish and even strip baits for trolling. We’ll also troll blue-white and red-black Ilander ballyhoo combos behind cigar sinkers ranging from 16 ounces to 3 pounds. We pick up a lot of our wahoo this way. Some may think we’re trolling too fast while underway at 10 to 12 knots, but plenty of fish are caught by boats trolling 15 to 18 knots. We catch different fish this way, including the occasional billfish.”

Miller’s baits go out immediately, sometimes in 50 feet of water, when the cero mackerel show up. “We’ll drag feathers across the patches and often catch a half-dozen ceros before hitting the reefs,” Miller says. “That’s the beauty of trolling, there’s no telling what you’ll catch on the way offshore.”

Think Ahead

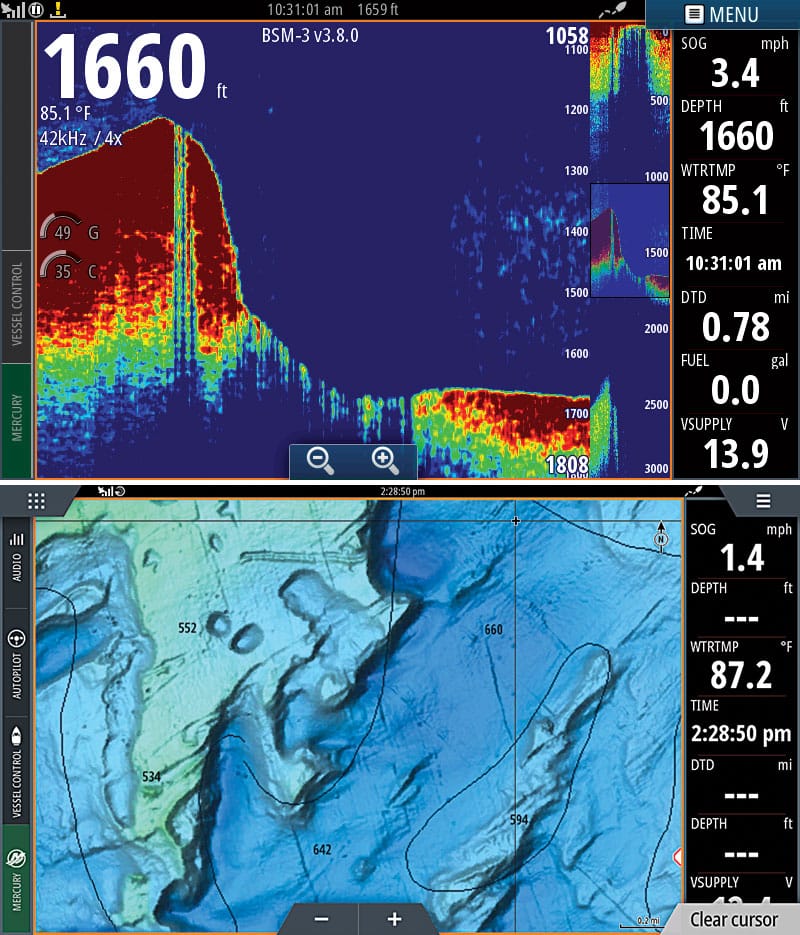

There are components involved in successful offshore trolling. Birds, weeds and debris aside, uncovering current edges, major surface-temperature breaks, tight bottom contours, prominent ocean-floor rises or crevices, and compact areas of craggy bottom bolster the odds of scoring. When washed by a current such bottom compositions spawn nutrient-rich upwellings, which attract bait and gamefish.

When focusing on ocean-floor rises and crevices, broaden the coverage area to include far up- and down-current of these finds. With high-profile bottom peaks, the heaviest upwellings occur on their up-current sides. But fishing their down-current sides, where upwellings sift and settle back down, also produces.

Subscription services such as ROFFS and Fish Mapping by SiriusXM Marine highlight major ocean-circulation features that can lead to fish, whereas ultra high-definition bathymetric imagery charts, such as Simrad’s C-Map Reveal, show bottom compositions in explicit detail. Studying in advance provides a much clearer picture of where to apply trolling efforts.

Read Next: Pro Trolling Techniques

Experiment with Baits and Speeds

Successful trolling also takes bait sizes and trolling speed adjustments in response to selective feeding behaviors. On numerous occasions, a spread of small ballyhoo skirted with small blue squid skirts capitalized on mahi keying in on small flying fish. Ditto with upscaling bait and lure size, opting for green hues when there’s an abundance of mahi.

As for trolling speeds, off Green Turtle Cay in the Bahamas this past May, Craig Hardy and I trolled a mix of medium and horse ballyhoo, each capped with a chugger head. Our average trolling speed centered around 10 knots. We ultimately dropped back to around 6 knots and saw an increase in strikes from white and blue marlin, as well as large mahi. The bottom line on trolling speeds: Quicker is not necessarily better, though we tend to gravitate that way when making an adjustment.

High Flyers of the Open Ocean

Consider this a shoutout to the worldwide baitfish that glides as well as birds along the ocean’s surface. The flying fish doesn’t actually fly, but it does utilize a burst of speed to rocket from the water and cruise above the waves with help from its oversize pectoral fins. The motion of flying fish escaping toward the skies looks similar to trolling spreads—and appears tantalizing to apex predators below.

Flying fish (family Exocoetidae) are found in the majority of tropical, subtropical, and even temperate waters. If you check FishBase online, its database tallies nearly 70 species—eight of those in the Gulf of Mexico alone. It doesn’t matter if you’re fishing off California, Barbados, Cape Verde, Spain, Japan or Australia; if there’s warm water nearby, flying fish aren’t far behind.

The Atlantic flying fish inhabits tropical Atlantic and Caribbean waters, featuring a black band prominent through its wings. The California flying fish is usually mentioned as the largest species, growing more than a foot long and targeted by commercial fishermen. Some flying fish might have a blunter nose, different coloring, odd-shaped tails or shorter pectoral fins, but all types have overwhelming similarities.

Species with large pelvic fins are recognized as four-winged flying fish. If you ever get your hands on a flying fish, see if you can identify if it’s two-winged or four-winged. Four-winged flyers absolutely soar.