As fast as our popping-cork combos hit the water, Capt. Abie Raymond and I hooked a spotted seatrout. These weren’t small ones either, but rather plump specimens bird-dogging a tightly bunched school of finger mullet. We released eight seatrout in short order and left them biting. Our objective for the day: Catch a variety of species available to us in Miami’s Biscayne Bay.

Raymond and I contained our fishing to the bay’s northern reaches, the exact waters we grew up fishing. In fact, most of our effort was north of the 79th Street Bridge. The environment here is far different from the heralded finger channels and bonefish flats within the bay’s expansive southern portion, south of Rickenbacker Causeway. It’s much narrower up north, with the Intracoastal Waterway, bridges, canals and grass flats as the angling focal points. North Biscayne Bay’s water clarity varies based on tides and winds, from a clean or turbid turquoise to cola-colored farther north in Dumfoundling Bay.

Everything Loves Shrimp

Our morning coincided with the beginning of an incoming tide. Given that tide and Raymond’s berth at the Bill Bird Marina charter docks, our first stop was Haulover Inlet, a few hundred yards away. Haulover is a narrow and somewhat shallow inlet (13 feet deep on average). Nicknamed the “bull ring,” it’s a tight and tricky place to fish. Water rages through the passage on calm days. Add in brisk easterly winds opposing an outgoing tide, and it becomes treacherous. However, it provides life to north Biscayne Bay, plus attracts a variety of forage and gamefish.

Haulover Inlet was calm that morning, and Raymond was interested in numbers of snook. His bait of choice? A live shrimp on a yellow 1/4-ounce jig. It was December, and the bay had experienced an early and rather strong shrimp run.

Raymond and I pitched to bridge pilings and groins, allowing the jigs to drift along bottom with the soft tide. He hooked up and brilliantly battled a snook away from the groins on light spinning tackle. Two things became apparent as we approached double-digit snook releases: Live shrimp was key in getting strikes (at least one snook regurgitated a bunch of them on the boat), as was light fluorocarbon leader.

“It’s a trade-off,” Raymond explains. “In the bay, 15-pound fluorocarbon is the ticket. However, with snook and larger tarpon, there’s a risk they’ll wear through the leader. But go heavier, and the bites really fall off.”

After releasing a dozen snook, we briefly fished for trout, then ventured up a few canals for more snook, jacks and anything else that would clobber a topwater plug, live shrimp or live pilchard. We enjoyed success there as well with all three offerings. The topwater snook bites were explosive and challenging, what with pulling them out from under docks and maneuvering around pilings in this city setting.

“So many of these canals are neglected,” Raymond says. “But they have so much potential. There are pilchards and, usually from late fall into early December, mullet venturing into them. Locate the bait, and snook, jacks, mangrove snapper, barracuda and even sharks won’t be far behind.”

Seatrout Headline the Show

Snook and tarpon often get more attention and hype, but the seatrout is north Biscayne Bay’s most symbolic species. The once expansive seagrasses here sustained robust seatrout populations. Many northern Miami-Dade County anglers—myself included—cut their fishing teeth on them. They were a dependable, fun and much sought-after species.

Unfortunately, poor water quality has killed much of the bay’s grasses over the decades. Lifeless mud and sand bottoms now exist where once fertile trout beds thrived. The culprits are many. However, the most damaging impacts come from spraying chemical herbicides within freshwater canals that empty into the bay (including the Miami River, Little River, Biscayne River Canal and Snake Creek); using herbicides and fertilizers on waterfront lawns, golf courses and parks; and raw sewage seeping into the bay from the aging septic tanks of some waterfront homes. (Not surprisingly, there’s a growing movement statewide to get waterfront homes converted from septic to sewer.) The bay has experienced two major fish kills in as many years, and north Biscayne Bay almost annually sees raw sewage discharges from a broken sewer line.

But folks are working hard to bring the bay back to life.

“We’re working with the Miami-Dade Water and Sewer Department to identify neighborhoods that are leaking the most nutrients due to septics so we can convert those to sewer,” says Todd Crowl, director of the Institute of Environment at Florida International University. “We’re also doing things such as a sponge restoration project (sponges filter dirty water). We’re working with North Bay Village to attempt a seagrass restoration site. And through the Health Board, we funded pilot projects that [utilize] new storm drains with filters.”

Signs of Seatrout Recovery

As Raymond and I settled into catching and releasing seatrout over a healthy swath of grass, he explained how critical it is to locate the right environments for seatrout.

“Seatrout like the shorter strands of seagrasses,” Raymond says. “Seagrasses with the snotty-looking tips are not good for seatrout. And those tall, lush grasses that rise close to the surface? They’re also not good seatrout habitat. It’s those patches of short blade grasses interspersed across bottom that hold them.”

As mentioned earlier, we released eight trout and lost a few more. What was surprising is that we were on the western side of the bay, which was once home to healthy seatrout populations.

“I noticed a decline in seatrout in 2012, and a big void between 2015 and 2019,” Raymond says. “There was seemingly no seatrout at all, and the entirety of grass flats from 79th Street to the Julia Tuttle Causeway died and turned to sand and algae bottom.

“The biologists hired by Miami Beach attribute the die-off to a vegetation growth speed so rapid that the top of the grass blades shaded their bases to where they couldn’t grow. The entire blade of grass needs to photosynthesize. The lack of light penetration prevented that, and the grasses began dying. The rapid speed of growth was attributed directly to an overload of fertilizers from canal runoffs.”

As of late, Raymond has been finding some healthy grasses on the bay’s western side and catching seatrout.

“Over the last two years, it seems like there has been a resurgence of seatrout, even along the bay’s western side,” he says. “Could it be somewhat from an improvement in water quality or the good shrimp runs we’ve been having? Like the old days, I now have fast-action spots for small seatrout, and spots where the action won’t be as fast but have better shots at larger seatrout.”

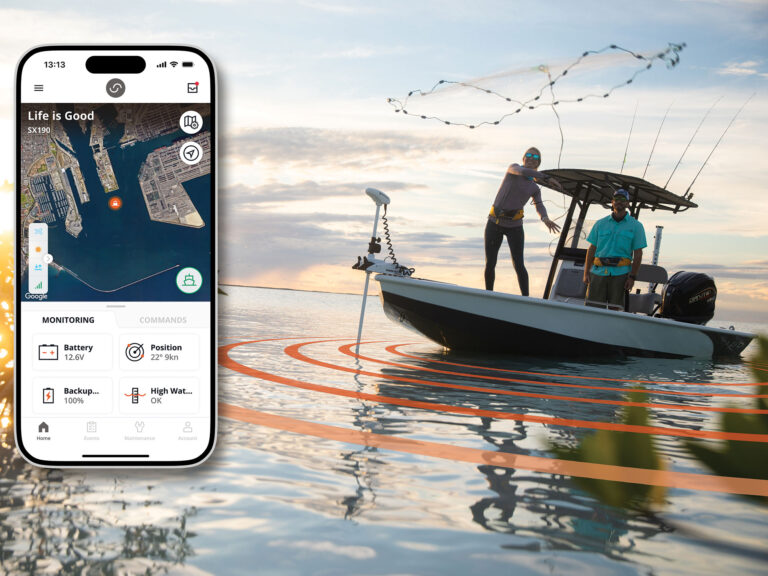

Light-Tackle Action

Use 10-pound line and 15-pound fluorocarbon leader for the best chance to trick seatrout. On this day, Raymond and I fished a live shrimp on a 1/4-ounce yellow jig head, 2 feet under a popping cork. Make a cast, let the jig settle for a few seconds, then pop the float every five to 10 seconds. Seatrout have delicate mouths, so keep the line tight when fighting fish.

I’ve enjoyed success with larger seatrout on Rapala SkitterWalk topwater plugs too. White is a standout color, especially with finger mullet present. Maintain that side-to-side darting and popping action. The biggest discipline when plug-fishing is not to get excited and rear back on the strike. Instead, maintain your rhythm and keep the plug in play. Once the fish pulls off line or you feel its weight, then rear back and have fun.

Fun Fishing

North Biscayne Bay has its share of fun fish too, namely mangrove snapper and sheepshead around structure, gag grouper in channels and around bridges, and jack crevalle in the channels.

“During fall and winter, we get some huge jacks of 15 to 30 pounds,” Raymond says. “You can see the huge wakes they’re pushing, and they can pop up anywhere in the bay. Get a live bait or plug in front of one, and you’ll get a long, hard fight.”

Read Next: Fishing for Bonefish in Biscayne Bay

King Mackerel in the Bay

The bay also has its oddities. For example, I caught and released a 12-pound black drum with Raymond during our outing. Hefty black drum aren’t all too common in this part of the state. Recently, Raymond released two 10-pound-class redfish in as many weeks, a true rarity for north Biscayne Bay.

But wait, there’s more! King mackerel in north Biscayne Bay? You better believe it.

Dumfoundling Bay sits at the extreme northern end of Biscayne Bay. Its ragged and deep bottom structures are the result of extensive dredging that helped create the masses of high-rise condos and buildings overshadowing the waters. Tarpon frequent Dumfoundling, particularly a deep hole just east of the ICW. During the fall mullet run, tarpon are solid and hungry. One method of catching them is by slow-trolling live bait, especially within this dig.

Anglers fishing the hole are often surprised by cutoffs, chalking them up to barracuda. However, these cutoffs are likely from juvenile king mackerel. I’ve caught several of them over the years while tarpon fishing; the leaders somehow avoided their razorlike teeth. I can only guess why they’re here. A partial nursery? The shrimp? Or are they following a main food source, finger mullet? Regardless, they’re here and a likely encounter when tarpon fishing. The kings even pick up that tannic-water coloration.

Miami Still Has It

Raymond and I returned to his slip around noon. The only gamefish we didn’t connect with was the tarpon. They’re usually solid here, especially during winter. We didn’t devote too much time to them this trip, though. Our day proved that even with some of the harsh environmental issues facing Biscayne Bay, the fishing within its northern reaches can be fast and varied. Let’s hope local and state politicians get serious about our water woes and help save Biscayne Bay—and all of Florida’s waters.