Not all the fish we hook can be trophies. Some of our catches can elicit groans rather than high fives. Here are eight fish (well, technically, seven) most anglers would rather not catch (and what to expect if you do have a close encounter). Read more about these Rodney Dangerfields of the fishing realm.

- Moray Eel

- Stingrays

- Toadfish

- Nurse Shark

- Pufferfish

- Scorpionfish

- Hagfish

- Alligators and Crocodiles

Moray Eel

If you fish Florida reefs at night, don’t be surprised to pull up one of these most unwanted of nasties. I still recall from my boyhood seeing these mucousy nightmarish creatures come up now and then on the lines of anglers as they dropped cigar minnows into dark waters. “When you fish lots of bait and you use lots of weight,” Karl, the mate, would sing out ala Dean Martin, “that’s a moray!” Too true.

I also recall headboat lore that served as a great reminder to keep appendages well away from those snapping, snaggle-toothed jaws — stories of hapless anglers who hadn’t been careful. Even after the moray’s head was cut off, it still took pliers to pry apart the awful jaws, it was said. I didn’t want to even think about subsequent infection.

The IGFA has records for a surprising number of moray species, 30 in all. While some species are on the mini side, others get disturbingly hefty. The all-tackle record for the common green moray weighed in at 33 pounds, 8 ounces, caught at Marathon Key, in March, 1997.

Simply being cautious may not be enough to stay out of harm’s way, because morays will wrap their own bodies into a ball as you reel them up, and they curl upward on the leader when you pull them out of the water. You do not want to get bitten by one of these things, which are as evil and ill-tempered as they look. Powerful jaws and large teeth will create a bloody mess where they clamp down. The slimy mucous that coats a moray’s mouth contains painful crinotoxins and hemolytic toxins that destroy red blood cells. And the distinct likelihood of secondary infections will add to one’s worry, not to mention time in the emergency room. Little wonder that many anglers whack the leader with a knife and just re-rig.

None of this is to say you can’t eat these unpleasant fish. Apparently their meat is considered quite tasty, at least in some areas, such as Japan. But plenty of accounts from U.S. anglers are less enthusiastic, citing soft flesh and lots of bones. But even more off-putting is (or should be) the very real possibility of big morays being ciguatoxic. (Ciguatera can build up in predators that eat reef fish, rendering the meat very poisonous to humans, though the toxin will be tasteless, odorless and can’t be removed by freezing or cooking.) Rewind to: Many anglers choose to whack the leader in two with a knife and just re-rig.

Stingrays

Three among the eight nasties here pose a double threat: They’ll mess you up if catch ‘em (and handle carelessly) or if you step on them. The stingray is one such.

That a stingray can really mess you up became abundantly clear from the tragic death of tv personality Steve Irwin in 2006, when the stinger of a 6½-foot short-tail stingray above which he was snorkeling in Australia pierced his abdomen and heart. And while other deaths from stingrays have occurred, odds are most angler encounters with their ghastly barb will be merely painful — but painful enough that the word “merely” would insult most victims.

The “stinger” on a ray, its tail spine, is a narrow, very sharp, flat, pointed affair — like a narrow knife — with a row of sharp, backward-facing barbs on each side. In other words: goes in easy, comes out hard (tearing flesh).

While many anglers have inadvertently stepped on a ray while wade-fishing and paid the price, others have gotten nailed while trying to unhook a ray. I would guess that’s more so with smaller rays, which can easily be held next to a boat or dropped onto the deck, or pulled onto a beach. Really big stingrays are probably most often (and most wisely) simply cut off at the leader.

And really big stingrays get huge. For example, the all-tackle world-record common southern stingray weighed in at 246 pounds (Galveston Bay in 1998). But that’s a mere pup compared to the freshwater rays of Southeast Asia, which can reach nearly 700 pounds, dwarfing men.

That said, a study of rays in Brazil revealed that smaller, younger rays had venom more potent and more capable of causing acute pain than older, larger rays, thanks to the presence of neuro-active peptides. (Older rays’ venom, on the other hand, was more likely to cause necrosis — blackening and destroying tissue.) Pick your poison.

But those pesky little rays that often grab baits (or get foul-hooked) can whip their tail around to ruin an angler’s day in the blink of an eye. One of the most common approaches to releasing smaller rays is to flip them over onto their back. That seems to make them a bit more docile for some reason, while also keeping their stinger pointed down and exposing the mouth, on the fish’s underside, to better remove a hook.

Still, given the zillions of encounters inshore anglers along the Gulf and Atlantic coasts have with common rays, a good number will be stung in a given year. Chances are that immediate relief won’t be available, since that involves the easiest, surest remedy: very hot water. That neutralizes stingray venom — as in fact it does most marine venoms. Beyond the swelling and pain, there is a very real risk of infection. Bad as all that is … it could be worse. You might catch one of several species of electric rays. Some can discharge more than 220 volts if you really piss them off. Ouch.

Toadfish

If gargoyles were fishes, they’d be toadfish. These unpleasant little critters are common in shallow coastal waters from Maine to Florida, and their aggressive feeding habits mean they’re frequently caught by anglers on small pieces of bait. This grinchiest of fishes with an angry visage twists and turns when caught, making it difficult to unhook. Woe to the careless finger that should end up in its exceptionally powerful jaws. If an oyster toadfish’s slightly venomous spines on its first dorsal fin or gill covers should pierce your skin, you won’t die, but you’ll be hurting for a while.

Oyster toads are abundant around rocks, rubble, wrecks, oyster reefs and debris. Even if you don’t catch one, you may still hear it: The species is well known for the loud foghorn-like sounds made by males at various times spring through fall, with special muscles that resonate against the swim bladder. And, yes, there is a world record for this nasty critter. That distinction is held by a 4-pound, 15-ounce monster toadfish from Ocracoke, North Carolina, in 1994.

The very similar Gulf toadfish lacks the venom in its spines, but is no less ugly and, for most anglers. annoying than the oyster toad. The fact is both species are edible and widely considered tasty. Seriously: You can find toadfish recipes online. The firm white meat is compared to lobster, rather like another, bigger, ugly bottom fish, the monkfish.

Warnings from many websites suggest eating toadfish may be lethal since the flesh of some species contains tetrodotoxin, the same powerful poison found in puffers that is deadly if eaten. But that’s where the confusing world of common names for fishes makes for more confusion. The toadfishes in this case are species of puffers in the Indian or far Pacific oceans, and not what we, in North America, call toadfishes. So bon appetite, American toadfish connoisseurs.

It’s worth nothing that the small, bottom-dwelling northern stargazer resembles toadfish, though generally found in more northerly, cooler waters. Try not to catch one: it’s even nastier, with large spines above its pec fins producing venom that causes pain, swelling and can lead to shock, plus it contains organs that produce an electric current.

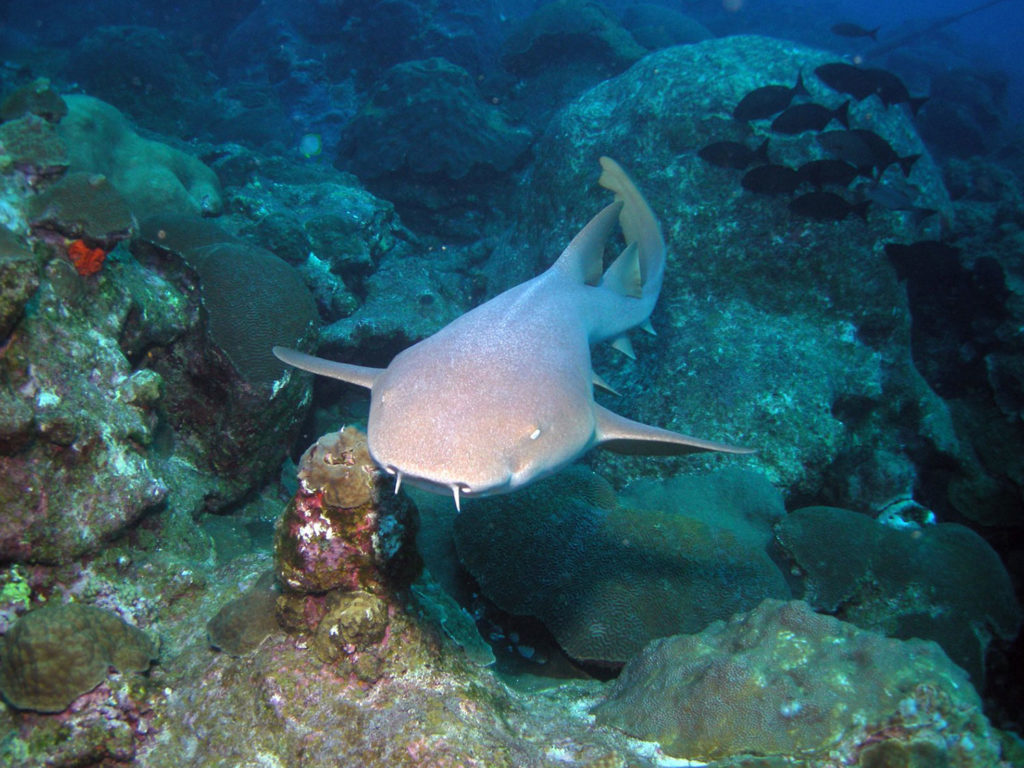

Nurse Shark

One might say a nurse shark fights as hard as an old boot, but one might also say that’s unfair to old boots. Not to be elitist, but the truth is few anglers want to hook a nurse shark. These benthic sharks so common in warm inshore waters of the Southeast basically just want to be left alone to sleep all day and roam the shallows at night for crustaceans and other slow-moving prey.

Few serious anglers will exhibit much excitement upon realizing they’ve hooked a nurse shark; only tourists and novice anglers might be thrilled at the idea of “shark fishing” for nurse sharks. Cranking a sluggish nursie to the boat isn’t much challenge; unhooking it can be more tricky. At some point, one has to acknowledge that these are, after all, sharks. Like any animal, docile can become nasty when threatened. That’s particularly true if pulled into a boat: a thrashing nurse shark with a snapping mouth can be more than fishermen planned on.

Nurse sharks can be as large as a man and a good bit larger. Case in point: The 263-pound, 12-ounce all-tackle IGFA world record from Port St. Joe, Florida, in 2007. At that size, particularly, the smart fisherman has no problem snipping the leader. Small nurse sharks offer a better chance at hook removal but even that can be tricky. Give a nurse the chance to clamp onto a body part and it may well hang around for a long time. Case in point, a woman bitten by a small nurse shark in South Florida in 2016 had to be driven to the hospital with the shark still attached.

Also, another bit of advice: Never kiss a nurse shark, tempting as that might be. One unfortunate fellow in 2013 off Key Largo, Florida, ended up needing 285 stitches to repair the damage to his face when the nurse shark returned his smooch with its own.

Fortunately, most anglers who catch nurse sharks stop at simply cursing them for wasting their time, destroying baits and damaging leaders; beating them to death seems a bit extreme. One commercial fisherman — yes, of course in Florida — was arrested a few years back after video footage was turned over to state officials showing him beating a nurse shark to death.

To avoid confusion, there is another nurse shark — a species known as the grey nurse in Australia, not to be confused with our own nursie. The grey nurse is unrelated, though it too is considered generally docile. But while the nurse shark’s small teeth barely show, the grey nurse shark sports one of the creepiest sets of dentures to stick out of the mouth of any shark species.

Pufferfish

Talk to inshore anglers who target redfish, trout and flounder on soft plastics about puffers. The word nuisance comes to mind, though at times “infuriating” would be more accurate. The boys at Berkley, who make Gulp! soft tails, must love them. That’s because in many places, at time, hordes of puffers wait to immediately bite off the bait behind the hook. At that point, you either pick up and move, and hope you can find a place that looks good but without the mob of blowfish, or you start casting hard lures (crankbaits). You can also throw tough TPE plastics such as those made by Z-Man. Still no guarantees, but they will survive the onslaught a bit longer.

But plenty of times, the little guys don’t stop when they’ve bitten off the bait, going after the jig or hook and whatever’s left on it, and you end up cranking in what feels like a Ziploc baggie filled with water. Then you have to take it off the hook while avoiding the cute little mouth with its little beaver-like teeth that can deliver a severe cut. They can be handled pretty easily as one might any small fish, though one popular approach calls for a wet towel to grasp the slippery fish. When they “blow up,” they’re not going to flop around, at least.

Fact is, these marine gadflies are delicious. With the opportunity at times to catch zillions, that could be good news. But it’s not. Flip side: many types of puffers in many areas carry toxins. That includes tetrodotoxin, named from the puffer family — Tetraodontidae — one of the world’s deadliest poisons, which takes up residence in a fish’s organs. That’s the source of fugu poisoning that, many years, kills dozens of diners in Japan — who eat it knowing the risk (is it that good?). A small number of specially trained chefs are licensed to prepare/cook the flesh to make it safe. Tetrodotoxin is also found in the deadly blue-ringed octopus of the Indo Pacific as well as in some species of poison-dart frogs in Costa Rica. The toxin kills by interfering with a human’s nervous system. There’s no known antidote.

Some puffers tested in Florida carried tetro. But more carried saxitoxin. While that may be somewhat less deadly than tetrodotoxin, it can be quite serious. Apparently saxitoxin wasn’t present in puffers in Florida until around the turn of this century, when puffers from eastern Florida’s Indian River estuary started making those who ate it very sick. Not all meat from various species of puffers around the U.S. is risky, but poisoning from puffers is so widespread that most fishermen release them — to gobble up more soft plastics.

Scorpionfish

Scorpaenidae is a huge family worldwide, with several hundred species in all, many found around the U.S. Those species range from the beautiful (lionfishes) to the interesting (scorpionfishes, including the California sculpin) to the truly hideous (stonefishes), and effects of the venom delivered by their spines vary, respectively, from unpleasantly painful to seriously painful to potentially deadly.

No matter what sort of scorpionfish an angler brings up, the crucial message is the same: Handle with care.

Lionfish are the least venomous in the group. Moreover, they’re among the species of scorpionfish that anglers might want to keep rather than get rid of right away, since they grow large enough to clean and offer superb filets. Releasing can be a challenge, with so many long spines sticking out from their bodies. But those who keep them often snap off those spines with pliers before filleting.

Many species of scorpionfishes (notably of the genus Scorpaena) are found around North America. All are laden with venomous spines, as many a careless angler has discovered — and lived to tell about it since envenomations from species of Scorpaena are rarely fatal, but involve extreme pain and may require weeks for victim to fully recover.

Most anglers are only too happy to unhook or cut off scorpionfish, but they’re actually fine eating. All of the Pacific Coast rockfishes (genus Sebastes), so popular as food fish belong to this family, and the California sculpin is popular for food among many recreational fishermen in the Golden State, who keep them — carefully. Most scorpionfish are modest in size: The California scorpionfish (sculpin) all-tackle record is a 4-pound, 6-ounce specimen from Cedros Island, Mexico, in 2006. The world record spotted scorpionfish common in the Southeast is 3 pounds, 14 ounces, caught in the Gulf of Mexico in 2015.

Then there’s the stonefish. Nasty to the Nth degree, scorpionfish of the genus Synanceia are frequently labeled as hideous, and with reason. Well named, the camouflaged bodies are barely discernible from an encrusted rock. Stonefish are less common and caught less often than scorpionfish, but when an angler does hook one, he has three sensible choices: cut the line, cut the line, or just cut the line. Stonefish are among the very most venomous fishes on earth. Their venom contains a strong neurotoxin and a cardiotoxin that act together to render many victims helpless.

Anglers wading in rocky/gravelly areas where they’re found can try to watch for stonefish but it can be nearly impossible. Their thick dorsal spines are hollow; pushing down on them — as would a foot (possibly even in a shoe) — forces venom out into the appendage. Then pain is immediate and from what survivors say — and many have survived stonefish encounters — beyond excruciating. Swelling may spread up an entire leg or arm within minutes followed by difficulty breathing, arrhythmia, paralysis and in some cases, death.

With all types of scorpionfish, treatment calls for immersion in the hottest water a victim can stand for 30 to 90 minutes. A hospital will treat symptoms and offer fluids and breathing support as necessary. If you’re going to impale yourself on a stonefish, do it in Australia, where hospitals are widely equipped with anti-venom that offers by far the best chance of survival and recovery.

Hagfish

Okay — disclaimer: The odds are you’ll never hook a hagfish. But if you happened to, you’d have the nastiest fish of them all.

These small, eel-like fish (of 76 species, none exceed about three feet — and, no, there is no IGFA world record for a hag!) live mostly in deep water around the world. They lack jaws (and eyes) and definitely won’t have a go at your speed jig. Rather, they rasp flesh off carcasses, often burrowing their way into said carcasses, then eating their way out.

If you were to snag one and bring it into a boat, it’s an experience that might require years of therapy to get over. Most of us would consider them pretty disgusting on the face of it, though some with a scientific bent might rather call them fascinating, but take them out of the water and you’ll find out why they’re also known as slime eels. Hagfish are noteworthy both for the amount of slime they produce and its qualities. In short, a hagfish can produce an unbelievable amount of slime. When tiny threads of its slime are released, each thread expands up to 10,000 times its original size. One small hagfish can create more than six gallons of slime. This slime spreads out and, with the mucin (mucous) it secretes, creates a network that water can barely pass through.

But don’t take my word for it. Type into a search engine “car covered in hagfish slime” and see what comes up. Ditto, type in “reeling in horrific hagfish — River Monsters.”

That said, if you did catch one, maybe you could sell it, if you were willing to fly to Korea with it. Turns out hagfish are a delicacy there, and there are now commercial fisheries for these nasty slimies in the Pacific Northwest. One man’s trash …

Alligators and Crocodiles

While you’re unlikely to hook a hagfish, the same can’t be said for anyone who fishes in gator country. No, these reptiles aren’t fish, but they can be pretty nasty if you poke a treble hook into their mouth.

From the Carolinas to Texas, anglers often share their fishing holes with the big lizards. Normally it’s a you-let-me-alone/I’ll-let-you-alone relationship. But alligators do have a propensity for chasing large, noisy surface lures. Often — fortunately — it’s the smaller specimens that are most aggressive, sometimes covering a considerable distance in a hurry to get their jaws on the hapless thing skittering away from them. Some anglers will mess with little gators when hooked boatside to try to get a lure back, but even that’s tricky with their thick skin, whipping tail, powerful legs with claws and, of course, those jaws lined with teeth.

By far the best advice to ensure you never have to deal with one of these nasty critters is simply to keep your lure away from them. Most of the time you can see ‘em tracking and rushing after a lure. Crank like crazy before they get too close and lunge (and avoid that temptation on a slow day to “just see if they really bite it”).

Fortunately, American anglers seldom have to deal with crocs, and never those of the saltwater variety found in Australia. That can’t be said for anglers like Peter Zeroni, a fishing writer/photographer who lives and fishes around Darwin. Lower rivers and estuaries there are ground zero for big, hungry and quite dangerous “salties,” as they call these monsters. Over many years, Zeroni or anglers with him, have unwittingly hooked a croc or two. Zeroni says if they’re under three feet long, it’s possible for one angler to hold them and another to remove treble hooks, though not easy and, besides, the lures are likely to pretty well damaged beyond repair at that point. “For bigger crocs on a hook, most fishos will rightly decide that losing an arm or worse isn’t a great idea, so they cut the leader.”