Few sights are more inspired and inspiring than scores of flying fish suddenly bursting from the water, beating their tails furiously across the surface, taxiing for takeoff. Their “flights” are a unique sight known well to bluewater anglers, but if you look beneath the surface, so to speak, you’ll find that flyers are just plain cool in so many ways.

Flying Fish Do Not Fly

We’re talking about fish, silly, and fish don’t have wings, since fish — rather like pigs — can’t fly. However, one type of fish sure can glide like champs, and do so with fins evolved to serve as wings. Flying fishes’ pectoral fins are long, reinforced affairs that when locked open sure do look and act like wings, catching air and using the very same aerodynamics to stay aloft for long periods.

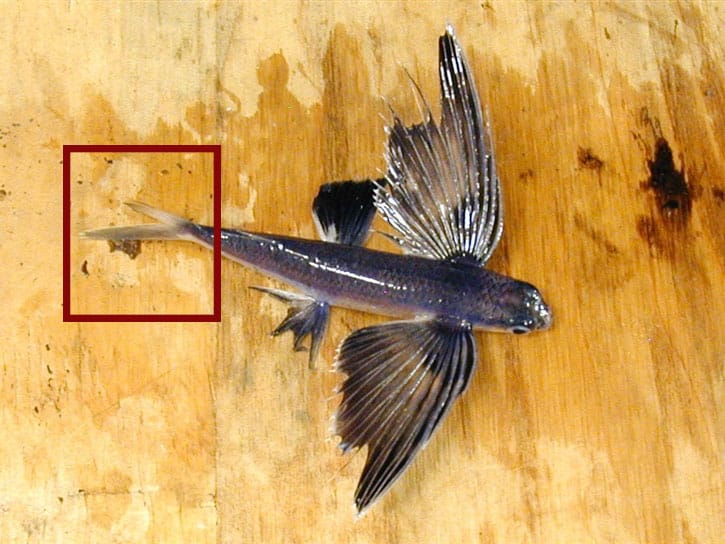

Flying Fish with Two or Four Wings

Flying fish really have no wings. But you know what we mean when talk about their “wings,” so check out the four-winged versions. That is, of at least 40 species worldwide, some have evolved secondary wings with pelvic fins, which are located behind the pectorals. Although smaller, the pelvic fins are still larger than would be normal and extend out just like the big pecs. The benefit, of course, would be additional lift. The effect, particularly when seen from a boat running offshore, looks for all the world like flying fish with four wings.

How Flying Fish Take Off

In terms of what in scientific circles is known as functional morphology, the flyer’s tail stands out. The forked tails of most fishes are homocercal, so they’re symmetrical with top and bottom lobes being mirror images. Take a look at the flyer. The fancy term for its tail is hypocercal. That’s because its ventral (lower) lobe is considerably longer than the upper lobe. The function of this comes into play when the speedy little devils start swimming fast beneath the waves for blast off as soon as they break the surface tension. Needing more speed to get airborne, that longer lower lobe gets cranking (to which any angler having watched flyers bursting out of the water can attest) for the needed thrust to catch air. Oh, and their ventral surface (their belly) is flattened to better catch air when aloft.

Flying Fish are Small and Speedy

Streamlined, torpedo-shaped flying fish can swim at speeds in excess of 35 mph. (They swim with their huge pectoral fins pressed tightly against their sides, not out, so they remain hydrodynamic.) For such a small fish, that’s a lot of speed. But they need that speed, requiring considerable velocity to break surface tension when they ascend for flight.

How Far Can Flying Fish Glide?

Yes, poor Wilbur and Orville Wright’s historic flight of 120 feet can’t hold a candle to flying fish, which have been known to glide more than two football fields in a single flight. And if you want to figure touch-and-go flights — wherein flyers on a glide path come into contact with the water just enough to start beating their lower tail until fully airborne again — they’ve been known to manage to glide about a fifth of a mile before finally returning to the water. And when they catch a good wind, they can glide up to 20 feet above the water (and hope no large seabirds are watching).

Flying Fish Glide Like Birds

That’s right: Actual flying fish have been tested in a wind tunnel. No, they weren’t alive, since wind tunnels use wind and not water. But Korean scientists essentially stuffed fresh flyers to retain body shape and affixed their fins open, then did the math. Their testing showed great efficiency, making them as capable gliders as are many birds.

Flying Fish Are Attracted to Lights at Night

Flying fish love to fly into bright lights at night. This is not a secret, at least not to sailboaters who travel the open ocean at night with lights on, and to other boaters offshore at night. The little fish will explode out of the water to land on decks. Thor Heyerdahl, in his famed Kon-Tiki journey, describes picking the fish up many mornings for breakfast. You can find videos online, such as Matt Watson’s crew during an Ultimate Fishing Show adventure, catching incoming fish in midair at night, using dip nets or even simply with hand grabs.

World-Record Flying Fish

Yep. There is one. A world record. From the records kept by the IGFA, we know that in June 2016, a chap by the name of Jim Bohary, set the record for the largest flying fish ever caught and registered officially: a one-pound Exocoetus volitans, aka tropical two-wing flyingfish, common in all tropical oceans. But I would be remiss not to point out that Jim’s record is a fragile one, since flyers do get considerably larger. A monster of two pounds is hardly unthinkable. But how the heck do you catch one? Read on.

Hook and Line Fishing for Flying Fish

That’s right. I mean, these things do have to eat. And yeah, lots of what they eat is rather planktonic and not what an angler can bait a hook with. But they also eat critters larger than that, so sabiki hooks will fool them. However, finding a school milling around for a sabiki drop is, well, unlikely. No problem. Slow troll through an area where you know they’re hanging out. You can see a video where a Vanuatu charter crew catches flyers one after the next by simply trolling little hooks with two-inch soft plastic tails on light mono leaders.

Eating Flyingfish for Dinner

Sure, flyers make fantastic baits. That’s why most anglers of the American persuasion want ‘em. But the fact is, it’s not only predatory fish who find them right tasty. In most areas of the world, the value of flying fish ranges from a delicacy to a staple. For centuries, they’ve been an important food source for Pacific islanders, often heading just past reefs at night to spear them by torchlight. They’re reputedly quite tasty, and the source of tobiko, the crunchy, bright orange flying fish roe of which Japanese are so found in their sushi.