A few years ago, the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) estimated that the mortality rate for released snook caught on the Gulf coast was only 2.13 percent. The research is clear that carefully releasing snook can help ensure that released fish continue to live after release. I think most of us understand, too, that this is a concept that holds true for just about any species of fish we catch and release. However, maintaining lower mortality rates among released fish requires that anglers take careful measures in how they catch, handle, and release the fish, particularly trophy sized fish.

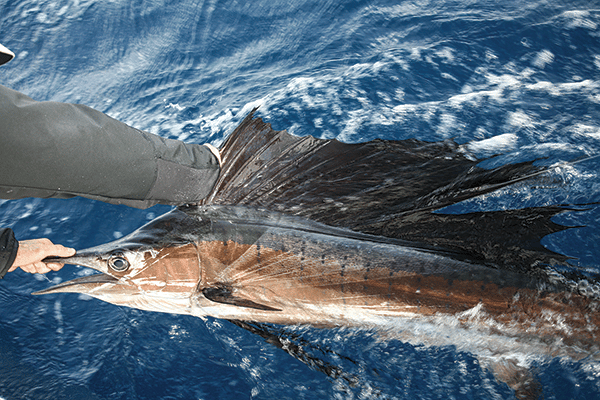

The key to successful releases requires that anglers understand basic aspects of proper release techniques, and that’s where things can get tricky. Different species of fish require different approaches to release. No longer can we think of release as simply chucking the fish back into the water. For example, reef fish require the use of a descent device rather than assuming the fish will swim back to depth on its own, while releasing a sailfish properly requires keeping the fish’s head facing into the flow of water to ensure that the water moves through the fish’s mouth and into its gills. So, releasing fish requires knowing about technique and about best practices for releasing specific species.

There are a few fundamental catch and release skills that all anglers should practice no matter the species of fish they are targeting:

Land Your Fish as Quickly as Possible

The longer you drag out the fight, the more exhausted the fish becomes, leaving it more vulnerable. A tired fish is likely to be too exhausted to out-swim a shark or barracuda. Often with trophy fish, anglers tend to be more cautious and deliberate in the fight for fear of losing the fish, but a drawn out fight can exhaust a fish and increase the risk post-release mortality.

Release Your Fish as Quickly as Possible

A fish that is out of the water is a fish that is not breathing correctly, and that fish can die from the lack of oxygen it takes from the water. Anglers tend to keep trophy fish out of the water longer to get more pictures of the prize catch, but your memento can prevent the fish from breathing while out of the water.

Avoid Gaffing Fish That You Plan To Release

Any gaff wound adds to a caught trophy fish’s trauma, and a poorly placed gaff puncture can itself be a mortal wound for a fish. Unless you plan to eat the fish, avoid using a gaff on your trophies — or any fish for that matter.

Wet Your Hands or Use Gloves

Wet hands put a barrier of water between your skin and the fish’s slime, which is there to protect the fish from disease. If you wipe the slime off with your bare hands, it is likely to leave the fish susceptible to disease. Gloves can also provide a barrier that is less likely to strip the slime off the fish.

Leave the Fish in the Water When Releasing It

When in the water, fish are buoyed by the water and there is less gravitational force exerted on their bodies. However, when they are lifted from the water gravity pulls them in ways that their bodies are not used to. This can cause significant internal injury. When it comes to trophy fish, anglers have a tendency to want to bring them out of the water to capture trophy pictures, but the fish will benefit in its recovery from being left in the water (plus, you can get much more dynamic pictures when you adjust to the fish in the water than you can with the cliched hero shot).

Keep Your Fish Horizontal

With fish that you are physically capable of lifting from the water, keep the fish horizontal. Do not lift them vertically by the mouth or tail. Research shows that doing so increases post-release mortality. If you do lift the fish from the water, release it headfirst and let the fish slide back into the water. Do not throw the fish back into the water (note that our language regarding release has changed form the old “did you throw it back” or “throw it back; it’s too small” to “did you release it” or “release it; it’s too small”). Don’t throw them back—literally.

Be Particularly Careful When You Can’t Reach the Water

When releasing a large fish from a pier or over a high transom or gunwale, anglers may not be able to carefully place the fish back in the water and end up dropping the fish over the edge. A long fall from a high point can injure a fish just as a fall from a high place might hurt you. When releasing big fish from a pier, use a drop net or landing net to lower the fish back to the water where it can swim away without having to first recover from a fall. When releasing a fish over a high gunwale, try to find the position on the boat lowest and closest to the water to reduce the fish’s fall.

Cut Leaders As Close to the Hook As Possible

Sometimes it can be difficult or impossible to remove a hook from a large fish’s mouth. For example, leaning over a transom to unhook a large billfish in rough water might not be feasible. Or, a hook might be buried deep in a fish’s mouth and removing it might take longer than you should have the fish out of the water. In such cases, clip the leader as close to the hook as possible. A dangling line can be dangerous to the fish, possibly sliding through the fish’s gills.

Use Barbless Hooks

Barbless hooks can make removing a hook from a fish’s mouth easier and will cause less damage to the fish’s mouth when you remove the hook. Likewise, with some species of fish with bonier mouths–like a tarpon, for example–a barbed hook may be difficult to remove efficiently.

Revive Tired Fish

Because predators like sharks and barracuda are more apt to catch a tired fish after release, it is best to revive the fish as much as possible before letting it swim away. To do so, just hold the fish with its head pointing into the current to allow the water to flow through the fish’s mouth and across its gills. If the fish does not revive quickly and swim away on its own, hold the fish’s mouth open and carefully move the fish forward to help push water through its mouth and across the gills. However, do not push the fish back and forth in the water — only forward. Fish don’t swim backward and forcing water backward through its gills can cause further stress and damage.

We understand this list might not be complete. Let us know some of your release efforts and context-specific strategies.