The pain in my right forearm had become unbearable. I shook it to relieve the discomfort. The spool on my reel was still missing 200 yards of line, and everyone on the boat was completely silent. At this point, I’d accepted reality: This was the toughest fight I’d ever encountered.

“We’re fishing the rigs. Are you coming?”

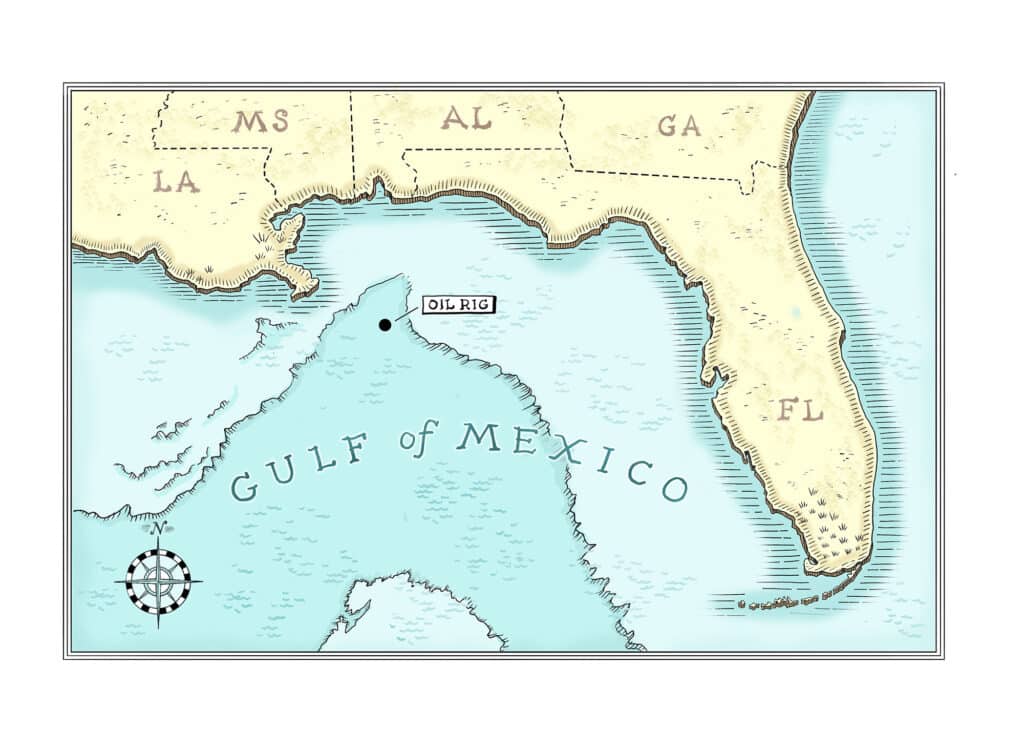

It was a sunny Monday morning in eastern Florida. “There are yellowfin tuna up to 100 pounds around the oil rigs off Alabama right now,” said Phil, who was coordinating this adventure for Salt Water Sportsman. I packed up my rods, tackle boxes and camera gear, put my truck in drive, and started the nine-hour journey to Alabama.

As the miles wound down, I thought about the footage I’d seen of fishing and diving around these rigs. There are around 3,500 of them, giant extraction machines that have become legendary fish attractors in the Gulf. I’d never fished an oil rig myself, but I’d grown up watching video after video of others lucky enough to run that far out. From spearfishing massive cubera snapper to ridiculous drone footage of foaming tuna blitzes, the stuff they’d shown me got my imagination racing. This could be one of the most memorable trips of my life.

I was one of six YouTube personalities on this trip, a group of guys Salt Water Sportsman pulled together to cover the bite. I’d only met one of the guys before, so I took some time at a rest stop to meet everyone. Jack Moran, known as “Yakin With Jack,” makes videos about fishing off kayaks around the Florida Panhandle. Phil Hollandsworth coordinates trips and shoots video for Salt Water Sportsman. Tony Faggioni creates surf-fishing content for his channel, “FishGum.” “Big John” McClain is a former professional hockey goalie who stands at a towering 6-foot-9 (and loves catching sharks from the beach). And then there was my friend Brad Warren, better known as “Bearded Brad” on YouTube and social media.

After a quick two hours of sleep in a friend’s guest room, we started to consolidate all of our gear to one truck. I glanced at my watch. It was 3:31 a.m. “Well, this is going to be a fun 24 hours.” Brad nodded sleepily in agreement as we drove the hour and a half to Dauphin Island. We loaded the boat, Capt. Kurt Tillman’s 39-foot Contender, shook hands with the new faces, and pulled out of the slip to start our long journey south.

The air was cold, just 44 degrees, which is very chilly when you’re running in an open boat at 40 mph. We had 60 miles to go before we got to our first stop, so we all did what we could to get comfortable. I found a cozy spot in some beanbag chairs and snuggled up between two grown men I had just met.

I felt myself starting to drift off into a light slumber when a bright flash of light jolted me awake. The captain had just driven by a natural gas rig. The massive structure was covered in lights like the house in National Lampoon’s Christmas Vacation. I gazed at the shrinking formation with my mind working. If we’re passing that up, what’s in store for us today?

Metal in the Food Chain

We stopped at a rig about 60 miles out to troll for wahoo while we waited for the tuna to wake up. As we set the lines, I stared at the giant structure to my left. No wonder these things house so many fish, I thought. The huge metal legs it stood on were covered in barnacles and other growth. Bait and microorganisms using the structure for food and shelter had attracted larger fish, creating an entire food chain. We could see proof of life on the screens of our electronics.

Trolling, though, is probably my least favorite way to fish. I need a rod in my hand to feel like I’m actually being productive. So, when Tillman suggested jigging around the next rig on our route, I started cranking up that wahoo rod faster than I’d ever reeled on anything.

The second rig we fished had sharks everywhere, dozens of 3- to 4-footers. I dropped a 400-gram slow-pitch jig, and as it reached 300 feet, my line went slack. I cranked fast and came tight to a blackfin, but as soon as I got within 30 feet, the sharks started swarming it. “Hang it up,” Tillman said. “We’re going to try something else.”

I took this time to pick both of our captains’ brains. We had two guides on board, Capt. TJ Haughton and Capt. Kurt Tillman. Both have a lifetime of experience fishing these waters, so I tried my best to be respectful when I asked, “Why aren’t we throwing poppers yet?”

There are two things to look for before you start fishing topwaters, they said. First, you need a lot of current. Second, there should be some type of bait on the surface. “Flying fish or bunker schools are what you want to see out here.” All morning there had been approximately zero knots of current and minimal surface activity, so I shut my mouth and let the professionals do what they do best.

Tillman mentioned that the current should pick up around 1 p.m., and at that time we’d likely start seeing fish busting on the surface. Like clockwork, we started to see small blowups on the other side of the rig. He thrust the throttle forward, and I grabbed my popping setup and started toward the bow.

The boat was barely out of gear when I hopped up on the gunwale and fired a cast right into the middle of a frenzied pod of tuna chasing bait. Pop, pop, bam! Excaept it wasn’t my popper that got whacked; Jack hooked up just to my left. Then, suddenly, my popper disappeared in a surface explosion, and I came tight to the boat’s first yellowfin of the trip.

The whole crew was fired up because it had been a few hours since we’d seen any action at all. What we didn’t know was that this bite would be nothing but an appetizer.

Hooking a Real One

We were running from oil rig to oil rig, trying to find more feeding tuna for the next three hours or so, ending up about 120 miles from shore. Finally, at the next rig, we all saw exactly what we had been looking for: strong current and fish busting on the surface. Though the blowups didn’t seem terribly large, I was excited for anything after the lull.

We pulled close to the action, and after a few casts, Brad hooked into a real one. With everyone on the boat watching Brad fight his fish, I tried to find spots where I wasn’t in the way but could still cast. The surface explosions had stopped, but I remembered the advice more-seasoned tuna anglers had given me: Keep popping, even when there’s no action.

I was half-watching Brad and half-watching my line when a fish inhaled my popper. As it ripped some drag and shook its head, I thought it had to be a 30- to 40-pound yellowfin. By this time, Brad’s fish had neared the boat. Haughton attempted to get a gaff on it, but the 80-pound fish shook its head and the hooks flew out. The entire boat was stunned. “That was the one!” Or so we thought.

Seconds after Brad’s fish threw the hook, my fish started picking up some steam, and I realized it was much bigger than 40 pounds. The beast decided to sound straight down, ripping 250 yards of line off my 10000 Saltiga in the blink of an eye. Now I knew I was in for it.

Over the years, I’ve listened to stories from more-seasoned anglers explaining how challenging a fight with a triple-digit tuna can be. Fighting one on popping tackle is the most painful fight of all, they’d said. Maybe it was arrogance, but for some reason I had never really believed them. I served in the Marines and come from a background where physical fitness is paramount to success. I remember thinking, Yeah, but that dude is super skinny. Or, He’s so out of shape; no wonder he struggled.

Boy, was I wrong. It took only 25 minutes for me to start wondering whether or not I was really cut out to land this fish solo. There had ever only been two things in my life that brought me to the same level of extended discomfort. The first was the long hikes with heavy packs that we would train with in the Marine Corps. The second was running a full-length marathon, when my brain would creep to thoughts like, You can quit. You don’t actually have to do this. Finding the willpower to overcome those thoughts led to some of the most rewarding moments of my life.

This fish was testing me just as hard as it pinwheeled 250 yards below the boat. I’d gain a few inches of line only to have the tuna strip another 5 to 10 yards back. Adjust the rod, change the grip, get a crank in, repeat. After an exhausting 40 minutes, I looked up to realize that all eight of us were silent. The sun had just set below the horizon, and an orange glow lit everything beautifully.

Haughton broke the quiet. “I’ve got deep color! You’re about 75 yards down. She’s big!” After another cramp-filled 10 minutes, we finally all got a good look at this fish. “It’s a massive bigeye!” Tillman called out.

“Two or three more circles and you can gaff her!” I said.

“It could be a lot more than that,” Haughton said. “I’ve gotta take the right shot or that bastard will pull me in.”

Over the years, I’ve seen many quality fish lost in the last few moments of a fight, so my anxiety was through the roof at this point. I wanted this fish in the boat badly.

Read Next: Oil Rig Tuna Fishing in Louisiana

In the end, it took two gaffs to get her into the boat. With a giant heave, both men lifted the huge tuna over the gunwale, and the whole boat exploded into cheers and celebration. Maybe it was exhaustion from the fight, but I found myself a little less outwardly enthusiastic than usual. More so than anything else, I just felt relief. This one was special. This was the one I’d been dreaming about, I thought.

“One-fifty-plus. That’s a fat girl right there,” Haughton said.

Exhausted and cramping heavily, I climbed into the tower with a Gatorade to watch the rest of the anglers cast. With the natural light now completely gone, I thought that the bite might be over. But in the glow from the oil rig, I witnessed something I could’ve never imagined. Everywhere I looked there were skipjack tuna and smaller fish busting on top—tiny whitecaps on a black sea, not formed by wind and current, but by thousands of feeding fish. This turned into one of those rare moments where I just sat down and took it all in.

In addition to my bigeye tuna, we boated five yellowfin tuna in the 60- to 100-pound class. The entire boat was ecstatic. This was the type of trip anglers dream about, a trip you tell stories about for the rest of your life.