It’s painful to lose a trophy to a snapped line or pulled hook when some minor drag adjustments would have prevented the mishap. Applying just the right amount of pressure throughout the fight is paramount to consistently land quality fish on light tackle.

What is Drag on a Fishing Reel?

When fish are too big to reel in quickly, drag is used to wear out the fish and prevent your fishing line from breaking. Drag serves two primary functions: It exerts constant pressure on a fish to wear it down, and it acts as a buffer to prevent tension from reaching the breaking point of the fishing line and terminal tackle, such as hooks, swivels, and the hardware on plugs and other lures. Many anglers estimate their drag setting by pulling line off a reel to gauge the tension, but unless you’ve developed that special touch over decades of fishing experience, you should play it safe and use a scale to achieve the desired drag setting before you get on the water.

Setting the Drag for Monofilament Line

Before the advent of superbraids, nylon monofilament was far and away the most popular type of fishing line. Therefore, drag-setting standards were developed around the use of monofilament, which stretches as much as 25 percent. While that stretch somewhat hinders hook-setting and the detection of subtle bites, especially when fishing in deep water, it also cushions against the sudden spikes in drag tension that occur when a sizable fish pounces on a bait, charges away from the boat, or surges into the air.

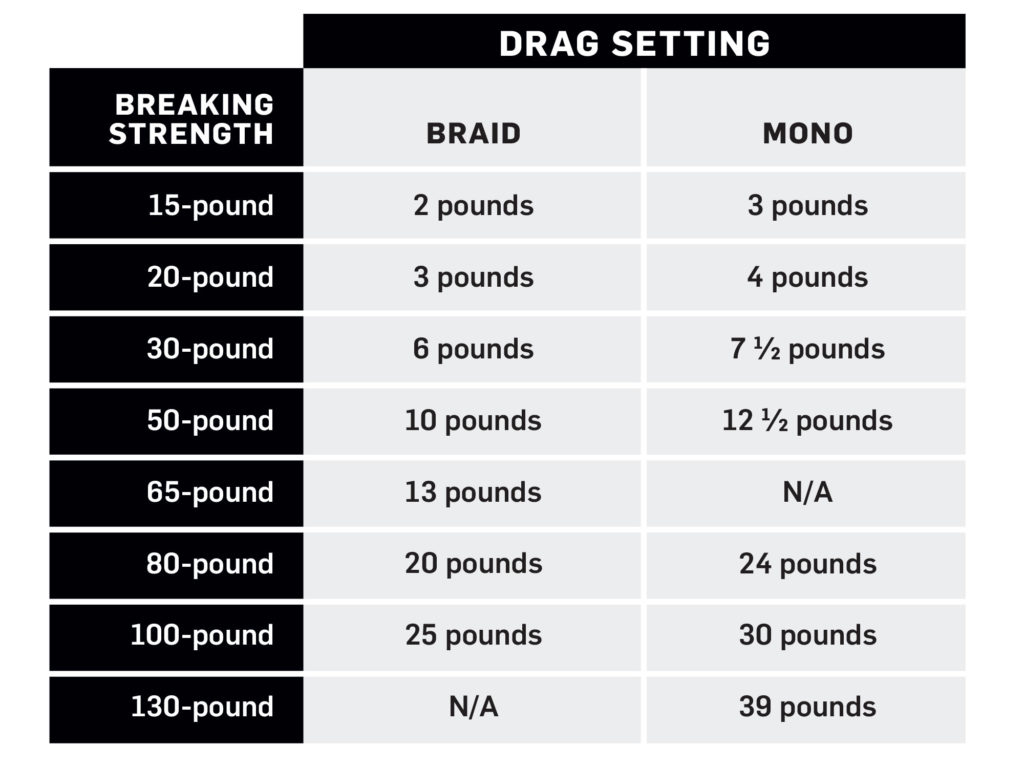

As a general rule, the proper drag setting for nylon mono lines up to 20-pound test is 20 percent of the breaking strength of the line. For 30- through 50-pound mono, it’s 25 percent of the breaking strength, and for 80- through 130-pound mono, it’s 30 percent. Of course, these are basic guidelines. The right drag setting varies according to the fishing scenario. A light drag is the right call when fishing light lines in open water, but considerably heavier drag is required to keep large striped bass, snook or grouper from breaking off on structure when fishing near bridge pilings, rocks or over a wreck.

Setting the Drag for Braided Line

Drag settings for braided lines, which lack the stretch of nylon, are different. Their near-zero stretch and smaller diameters result in better hook-sets, faster sink rates and a much better feel. But the cushion against sudden spikes in tension is nonexistent, so lighter drag settings are in order.

With braided lines up to 20-pound-test, set the drag at 15 percent of the line’s breaking strength. With 30- through 65-pound braid, set it at 20 percent. With braid that tests at more than 65 pounds, go with 25 percent. Again, these are only basic guidelines, and you must increase or decrease drag tension based on the location and the circumstances.

Braided Lines Are Stronger Than What Their Label Says

Be aware that, unless it says IGFA or tournament on the label, most fishing lines aren’t classified by their actual breaking strengths. The difference between a line’s weight classification and its real breaking strength is usually greatest in braids. For instance, some 30-pound braided lines break at more than 40 pounds, so you may need to do a little digging (check manufacturer websites) to ensure you don’t set the drag unnecessarily light.

Use Your Hand to Slow Down A Fighting Fish

Because of their inaccuracies, major drag-setting adjustments in the heat of a fight often prove costly. If additional pressure is needed to stop or turn a fish, “feather” or “cup” the spool of your reel instead. You can also pull sideways, bending the rod a little more. Should that fish make a sudden run or jump, the extra pressure is instantly abated by simply removing your hand from the spool and aiming the rod tip in the fish’s direction. Once the fish settles down, reapply the additional pressure to shorten the battle.

When to Back off the Fishing Reel Drag Pressure

The many variables that increase the drag tension during a battle include the resistance of the line, which steadily increases as a fish pulls more and more line during a long run; the diminishing diameter of a spool as the line peels out of the reel; and even the degree of bend in your rod.

The initial drag setting should buy you enough time to give chase and reclaim lost line. However, when fighting a fish from a stationary boat or when a fish won’t slow down, begin backing off the drag to compensate for the increasing pressure on the line. As the fish settles down and you regain a safe amount of line, start tightening the drag little by little, without exceeding the original setting.