“We hand-cranked swords for a number of years, but the ability to use an electric reel has been instrumental in expanding the fishery,” says Capt. Nick Stanczyk. In case you aren’t familiar, the Stanczyk family are the proprietors of Bud N’ Mary’s Marina in Islamorada, Florida. Nick, his brother Scott, father Richard and Vic Gaspeny are the pioneers of the daytime swordfish fishery, deep-dropping baits and weights sometimes in excess of 10 pounds to depths of 2,500 feet or more. Over the years, they have perfected their craft.

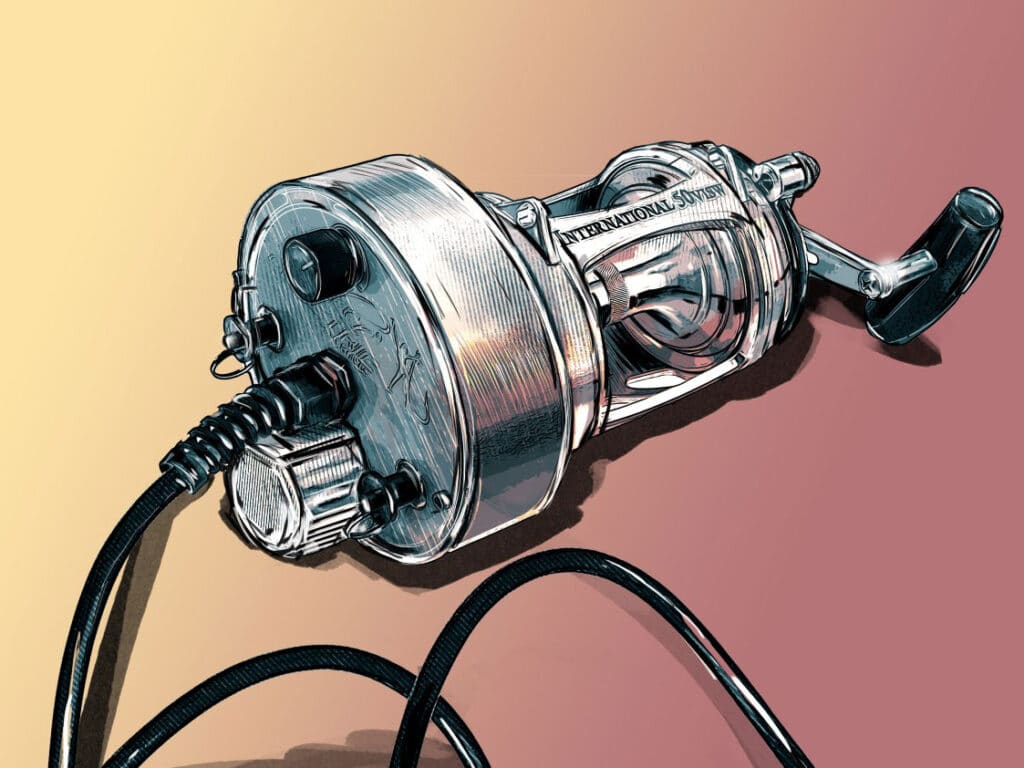

“I’ve caught about 2,000 swordfish. Half of those fish were hand-cranked, and the rest came on electric reels,” says Stanczyk, who added electric reels to his repertoire around 2014. His 42-foot Freeman, Broad Minded, was outfitted with deep-dropping in mind. This includes a number of outlets to provide juice to the Hooker Electric-powered Penn Internationals he has taken to using.

“We’re able to change spots more quickly thanks to the electric reels,” Stanczyk says. “Instead of spending 30 to 40 minutes to retrieve a weight, the electric reels get it done in about seven or eight minutes. That’s a big time savings.” The increased efficiency has also allowed Stanczyk to fish multiple rods, something he says wasn’t feasible before he made the switch to electric reels. “Before electrics, we only fished one rod. Now we fish at least two. With the right crew, three is possible.”

You can still chase records with these reels, as long as you don’t use power to deploy baits or fight fish. “About a year ago, the IGFA approved the use of detachable electric reels. So now anglers can still qualify for records, as long as the motor isn’t attached to the reel and anglers manually reel in the fish,” says Trista Evans, vice president of Hooker Electric Reels. She notes that her company’s 50-, 70- and 80-size reels are the most popular with those chasing swords during the day. The motors in the detachable (hand-crank model) and auto-stop series, which can be programmed to stop reeling at a set point, can utilize both 12- or 24-volt power. This makes them ideal for use on both older vessels and today’s crop of big center-consoles.

For swords, Stanczyk prefers the Penn International 80 VISW Detachable from Hooker. The detachable nature of the electric motor on the Hooker-Penn reel makes it possible to hand-crank the fish in on stand-up gear or with the rod stuffed in a holder.

Nearly 50 Years of Electrics

Despite a recent renaissance among recreational anglers, electric reels are nothing new.

Some of these are purpose-built designs that look more like industrial equipment than something you’d expect to find on a boat. Others have a more typical form. Some add power by clamping a motor onto an existing reel, using an adapter to transfer power to the reel’s arbor. Others, like the Hooker mentioned earlier, have a more seamless look. Some allow you to hand-crank the reel if you so choose, while others have no such provision. All are powered by direct current, typically provided by the boat, using anywhere from 12 to 32 volts.

Lindgren-Pitman has been building electric reels in Florida since 1975, when it introduced an electric conversion for a 12/0 Penn Senator. The company has since upgraded from a 300-square-foot shop to a 37,000-square-foot facility, but it stayed in Pompano Beach and still builds just about everything in-house.

“South Florida is the heart of daytime swordfishing, and we build a number of models with that in mind,” says Timothy Pickett, sales engineer at Lindgren-Pitman. Many of Lindgren-Pitman’s reels are built with commercial uses in mind, so they utilize 24- or 32-volt drive motors. But with the increase in recreational electric-reel use and a shift in the vessels anglers were taking offshore, the company made a change. “With the increased use of outboard-powered boats, we switched over to mostly 12-volt systems.”

The company’s S2-1200 and SV-1200, using commonly available 12-volt electrical systems, are favorites of recreational anglers. On its bigger commercial models, Lindgren-Pitman found that the weak part was often the reel itself, so it built the chassis from scratch with the intense torque of direct current in mind. This design transferred to the smaller models as well. It also included a levelwind, which automates more of the operation. Another unique feature is swappable spools, allowing anglers to change rigs quickly in the event of a break-off. But there’s no handle, so you have to let these reels bring in the line on their own.

Read Next: Daytime Swordfishing

The Hand-Crank Option

Hooker Electric’s motors work as an add-on to an existing reel—such as Penn’s International VI or Shimano’s Tiagra—but they were designed as a seamless addition that complements the host reel’s function. In fact, with the sale of Hooker Electric to Pure Fishing finalized in 2020, a section of the factory that builds Penn Internationals in Pennsylvania is now devoted to assembling Hooker Electric reels, as well as warranty work to keep customers happy and out on the water. Evans and Hooker President Tom Sandstrom couldn’t be happier with adding an electric reel to Pure Fishing’s lineup.

Just about every manufacturer has an electric offering these days. In addition to electric-reel specialists Hooker, Lindgren-Pitman and Kristal, anglers can find offerings from Daiwa and Shimano. Some of these are designed for automating kite spreads, pulling dredges, or making bottomfishing easier. Daiwa’s new Tanacom 1200 features a powerful 12-volt motor that can handle deepwater heavyweights. Shimano’s Beastmaster is another good choice for swords, but there are rumors of electric-reel updates from Shimano at ICAST this year.

Unfair Advantage?

So, does using an electric reel take some of the sport out of fishing? Not according to Stanczyk. “No doubt, electrics help keep steady tension on a fish, but there’s a lot more to it than that. The biggest challenge for us charter fishing all the time is finding fish consistently, and then boathandling with a wild swordfish on the leader.” Stanczyk adds that he’s seen sword fights lasting eight hours. “A lot can happen in that time. A lot can still go wrong with terminal tackle.”