Fishing for bonefish with a fly rod is challenging enough without handicapping yourself by poor preparation in both the gear and skill department. Let’s face it, foraging in water a scant few inches deep would make any fish skittish. That goes double for homegrown bones. Those wary residents of the Florida Keys and Miami’s Biscayne Bay, which are subject to appreciable angling pressure and boat traffic.

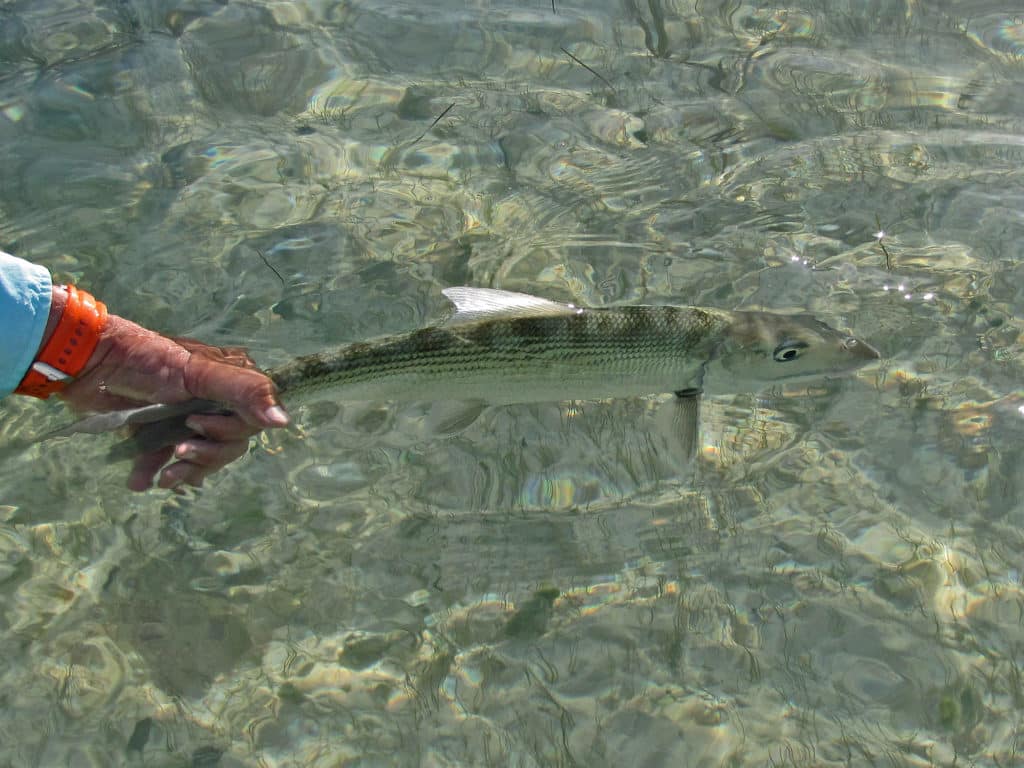

Some of the Bahamas Out Islands, Cuba, Mexico and parts of Central and South America offer fish somewhat less panicky that often afford beginner and intermediate fly fishers better odds to hook up. Florida’s fish, however, tend to be bigger on average, but most have also grown increasingly wary.

Whether or not you believe bonefish have cornered the market in paranoia, targeting the grey ghost anywhere calls for stealthy stalking via skiff or afoot. And even the ultra fearful specimens can be approachable when the conditions are right.

TAILERS

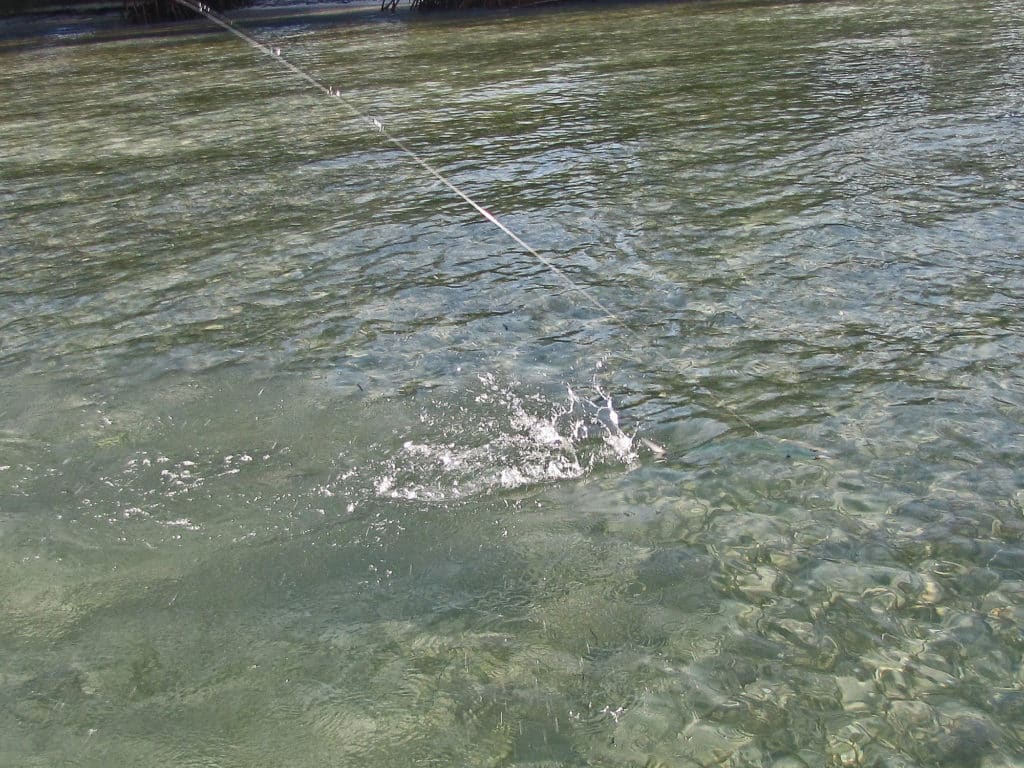

Tailing bonefish are the saltwater fly rodder’s Holy Grail, and for good reason: there is nothing quite as exhilarating as stalking tailers. The sight of that glistening, wet tail thrills even seasoned veterans. Of course, when their tails and sometimes dorsals break the surface, bonefish are usually looking for food in skinny water. They feel most conspicuous in such shallow digs, and will bolt at the slightest provocation. So, not only must you cast accurately, but you also need to anticipate a fish’s movements and lead it just enough to avoid spooking it with your presentation. Land your fly too far ahead and the bone could alter course and never see it. Land it too close, and sayonara.

A rare occurrence in Florida, where bonefish tend to tail alone or in pairs, smaller fish often travel and tail en masse in places like the Bahamas and Central America, and visiting anglers commonly encounter groups of half a dozen to schools of a hundred or more with their caudal fins poking through the surface as they methodically scour the bottom of a shallow flat for grub.

WHEN TO CAST

As hard as it is to resist dropping a cast into their midst, don’t do it! You’re bound to send the entire school dashing for the horizon as a result. It’s much better to pick out a fish and make a proper cast to that particular individual. As for single bones, they don’t tail aggressively in one spot, practically tumbling over in the process, like redfish often do. They usually tail once, move a bit, then tail again as they work into the current. You might not get more than one or two shots, so you better make them count.

When I cast to a tailer, I wait until the tail pops up. That signals the bone is engrossed in “blowing” out prey and its head is down, so the fish probably won’t see your line and leader in the air, and the fly’s splashdown isn’t as likely to be detected. When the tail comes up, it’s easy to see, or at least estimate, where the head is. In turn, that enables you to predict the direction the bone will take when it moves again, and gauge where to place your cast. If you can get your fly within 2 feet of the fish while it is tailing, you are in business. Once the tail goes down and the fish’s eyes are up, minimal stripping is usually required to elicit a take. It may very well pounce on the fly with the slightest manipulation from you. Word to the wise, always watch for that tail to pop up when the fish is over the fly, it’s often a sign it has eaten your offering. Immediately get tight to the fish and strip strike.

CRUISERS

Though it’s not always the case, cruising bonefish are considered easier to catch than tailers. That’s because they are often in slightly deeper water — from 18 inches to 4 feet or so — where they can still be sight-fished under bright skies. When it’s shallow enough, or when they swim closer to the surface, cruisers push a V-shaped wake, and you need wakes to spot them during early morning or late evening hours. On sunny days, between 9 a.m. and 4 p.m., the silhouettes or shadows of the fish are more easily spotted against the bottom.

The key to success with cruising bonefish is to gauge their speed and determine how much of a lead will be required when you cast. Get your fly in front quickly, so it is at the fish’s eye level, or preferably a bit below, once the bonefish comes upon it. If you spot a fish close to the boat at the last second, you have no choice but to go for broke and cast close to the fish. Sometimes, the bone will make a grab as the fly sinks, without you stripping at all.

POLING vs WADING

You can stalk and cast to tailing bonefish from a skiff, though it had better float really shallow, and pole silently without hull slap and without pushing a perceptible “P-wake” (pressure wake) ahead. No bonefish will tolerate either. And where the bottom is firm enough, you increase your odds of hooking up by wading quietly. Wading for bones is the ultimate hunt, and it’s often the only alternative when the fish are up on extreme shallows. Far less conspicuous than a boat, a wader can get much closer to the fish and position better for an easy shot.

Wet wading, since bonefish are a warm-water species, only calls for a pair of zippered rubber-sole flats booties, though some waders prefer sturdier, shin-high specialized footwear. When bonefishing in the Bahamas and other locales with firm sand bottom, you can barefoot it. Either way, it’s imperative to slowly shuffle your feet along the bottom to minimize noise and avoid stepping on stingrays. If you’ll be bailing out of a skiff to wade, a couple of flies, snips, and spare tippet is all you need to carry. If you are embarking on a roadside wading session, a fanny pack or backpack containing more fly options, pliers, extra leaders and tippet, a small camera, and a water bottle is in order.

LINE MANAGEMENT

When it comes to fly line management, there are good news and bad. The good news is that, since you can get closer to the fish when you wade, you need less loose line off your reel than you do fishing from the skiff. The bad news, for some, is that you have to somehow carry a handful of loops of line without tangling as you wade. Stripping baskets, so commonly used by fly fishers fishing the surf, are not popular with bonefishers. Instead, most prefer to grip three or four large loops of fly line, ready to shoot, in their line hand. Or, as I have done for years, simply allow the loose line to trail behind, which works well when there isn’t a lot of grass on the surface. By the way, before you wade, clean your fly line well, and consider dressing it with a floatant, which makes it easier to pick up off the water to initiate your casts.

TAILOR YOUR TACKLE

Tackle is not so much dictated by the size of the fish as it is the size of the flies, the wind conditions, and the depth of the water. Whether stalking 5-pound schoolies or single 10-pound-plus trophies, an 8- or 9-weight rod is most often the best tool. In super-calm conditions and when the fish are tailing in the shallowest water, a 7-, or even a 6-weight may get the nod. A light line impact is always preferable, so a longer leader — 11 feet or more — is a real plus to put more distance between the fly and fly line upon water entry.

FLY PATTERNS

Fly choices for bonefish are made considering various factors: water depth, color of the bottom, the local prey, and the size of the bonefish. For Florida fish, which are big and prefer bigger flies, crab patterns lead the way. Smaller Caribbean bones are commonly fished with smaller crab and shrimp patterns tied on No. 6 hooks, and even 8s in some areas. But No. 4 hooks have long been the standard in Florida waters, and many guides and veteran fly anglers now tie “meatier” patterns on No. 2 and No. 1 hooks, in some cases. This is especially true for the giant fish that frequent the flats of Islamorada and Biscayne Bay, particularly the 10- to 13-pound giants that show up in the spring.

The list of popular bonefish patterns is a long one, and innovative tiers often come up with hot new patterns. But you don’t need 50 different flies in your box. A good Florida fly selection will include: Clouser Minnows, Borski’s Critter Crab and Swimming Shrimp, small Merkins, mantis and snapping shrimp imitations, and perhaps a few patterns that mimic small gobies. I’d also stick a few Gotchas in the fly box. They don’t just catch bones in the Bahamas! Mix the flies up, some weighted with lead dumbbell eyes and bead chain, some some unweighted, and on No. 2 and 4 hooks.

For the Bahamas and Mexico, you’ll need more flies in lighter colors for the sandy flats, tied on No. 4 and 6 hooks. Bead chain eyes add enough weight for most cases, but it’s a good idea to include a few flies with slightly heavier lead eyes. Before traveling, always research the best flies for the specific destination. Your outfitter or guide is usually the best source. Standards include the Gotcha, Crazy Charley, Bahama Mama, Bonefish Scampi, Foxy Clouser, Borski Critter Crab, Raghead Crab, and Bonefish Bitters.

LINES AND LEADERS

Floating lines are all you need, and so-called “tropical lines” with stiffer cores and coatings stand up to summer heat best. Come winter, however, water temps sometimes dip to the lower tolerance range for bonefishing (upper 60s to low 70s) and make such lines coily, requiring constant stretching to eliminate line memory. Instead of fuzzing with unruly lines, I go to fly lines with more supple braided nylon cores.

A standard weight-forward taper line serves well, though the more aggressive “flats tapers” (also called bonefish tapers) pack more weight up front and have a shorter front taper, requiring less line outside the rod tip to turn over flies. Simply put, they excel for quick, short casts under 50 feet. Line color is of secondary importance. Some fly fishers swear by dull color lines, others feel they cast better with bright-colored lines. The latest trend: clear floating lines have gained some popularity, though they make it tougher to gauge where the leader starts and where your fly is as you attempt to entice a fish.

A bonefish leader is typically tapered from a 40-pound-test butt to an 8- to 12-pound tippet. Except for the knotless kind extruded from fluorocarbon or from nylon monofilament, most leaders have four or five step-down sections, joined by blood or uni-knots. Ideal lengths range from nine to as many as 14 feet, depending on conditions, and the wariness of the fish. For cruisers in deeper water, leaders shorter than 10 feet are fine. But longer leaders are better for tailers.