In North Carolina, where redfish are called puppy drum until they mature and attain the large proportions that earn them the label of red drum (bull reds in most other places), a consistent fishery for truly giant specimens has made the waters of the Outer Banks famous.

Persistent anglers spend countless hours in the surf waiting for these jumbo reds to blitz the beach. Others pound hundreds of miles on their boats, scanning the horizon for explosions in the water or the sight of large schools of red drum — appropriately dubbed pumpkin patches — that roam the coast from fall through spring, the same fish that fly rodders found more catchable in the shallow waters of Pamlico Sound and the Neuse River, where they spend their summers.

Reports of vast concentrations of giant reds in the Tarheel State’s inshore waters first spread in the 90s, as local guides hosted outdoor writers and TV show crews, which promptly told the story of this great fishery easily accessed by small boats. As popularity grew, concerns over protection of spawning stocks prompted North Carolina Sea Grant to fund a variety of studies. I had the privilege to participate in this early research, and the hours I spent following and observing these fish proved invaluable.

As a guide, I put the gained knowledge to good use, anticipating prime feeding periods in the afternoons and evenings, and knowing the shoals of the lower Neuse, which go by the names like Maw Point, Gum Thicket, Swan Island and Lighthouse, were reliable spots to locate giant reds on the prowl. The tops of these shoals are four to 12 feet deep and their edges drop sharply into the Neuse River bottom, never deeper than 20 feet. This main dropoff gets most of the giant red drum traffic. During tracking with a hydrophone or an underwater directional microphone, we observed tagged fish cruising these drop offs, often sliding up on a shoal, then down to deeper water, feeding on anything that got stirred up along the way, often responding to chum lines from boating anglers in the area.

But it wasn’t until a decade later that local guides figured out what those “laid up” red drum were doing and how to catch them. It was Capt. Gary Dubiel who fine-tuned techniques that include consistently catching them on the fly.

Dubiel realized that these fish are extremely bait oriented, patient and stealthy, preferring to quietly stalk schooling baitfish — menhaden, most often — to pick off any stragglers injured by attacks from slashing bluefish, Spanish mackerel or jacks, and frequently excited and urged to feed by the foraging activities of or said predators or other red drum.

To take advantage of said predatory response, conventional anglers use large popping corks with big concave faces that, jerked vigorously, produce the kind of loud noise and splash that mimic surface feeding. Dubiel took note, and adapted said technique for fly fishing.

In the search of a popper that move lots of water and was easy to rig and cast, he developed the Pop N Fly, a foam popper with in-line wire and a loop on both ends. The leader’s butt section is attached to one, two feet of 20-pound fluorocarbon plus two feet of class tippet and the fly are affixed to the other.

A 10-weight fly line can handle Dubiel’s rig. He prefers Scientific Anglers’ Titan Taper line, which he claims will throw the popper and a weighted Lil Haden, a fly pattern he concocted, with ease. The Lil Haden is a simple fly that incorporates some lead wire and a 4/0 or 5/0 hook. White and about any other color combination works in the usually clear, but tannic-stained water of the Neuse River.

Whatever your choice of fly, it should be weighted, but not so heavy that it sinks your popper. Aside from the Lil Haden and popper that Dubiel uses, I’ve had good results with a white, 5-inch Half-and-Half fly on 50-pound leader suspended 12 inches below a large Cam Sigler popper head pegged with a toothpick just above the knot connecting the bite tippet.

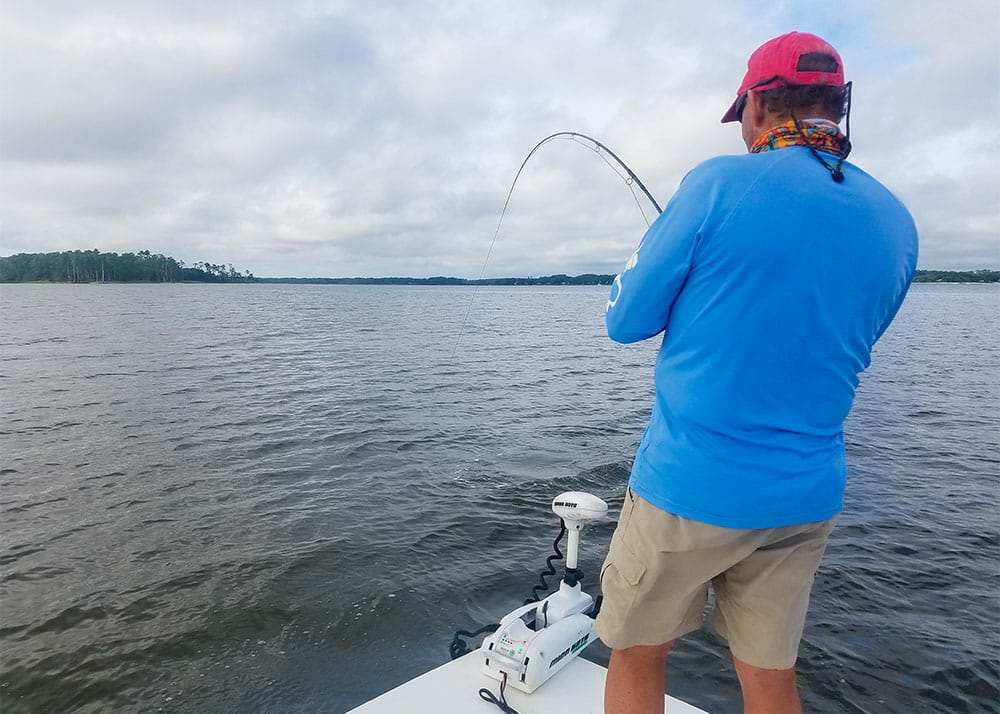

You need to be drifting and casting across or into the wind, so you won’t need to cast very far. Don’t waste time with lots of false casts trying to get a few extra feet of distance, just get the fly in the water and let it drift away from the boat. Once the drift takes all the slack out of the fly line, give it a good jerk, pause to again let the line straighten out, and give it another jerk. Unless specifically casting to a pod of bait, leave the fly and popper in the water and keep repeating the procedure to draw in any nearby bull reds.

Don’t worry about keeping the fly moving. The fish will find it and smack it, even if only 20 or 30 feet from the boat The bite often happens a few seconds after the pop, either as the fly flutters down or even when it’s sitting still. The key is simply to keep the fly in the water. For this technique, patience is actually more important than long, accurate fly casting.

When you do get the bite, keep stripping until you come tight and you’re able to set the hook. Then focus on clearing the loose line and fight the fish from the reel. Always keep quiet and stay on your toes, many bites come right at your rod tip from fish you just drifted over.

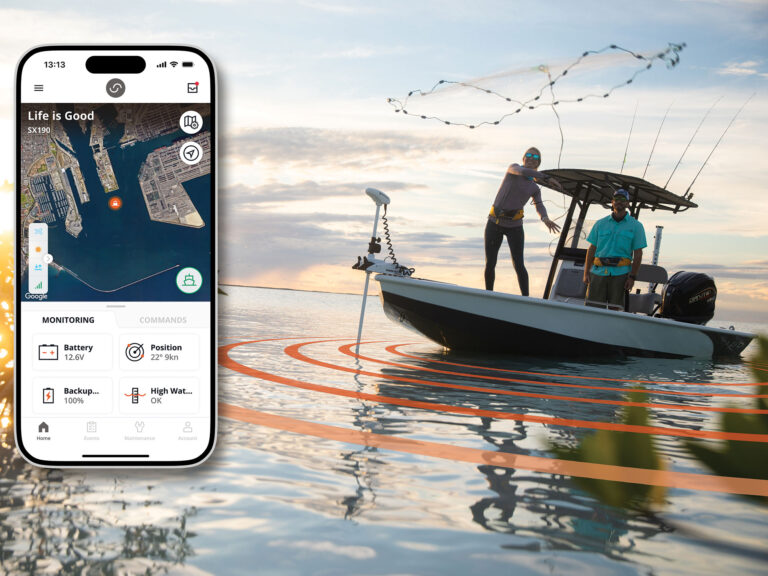

The Neuse River is not much deeper than a swimming pool, and these fish can be extremely sensitive to boat traffic and noise. Use a trolling motor at the lowest possible speed to help control your drift. When approaching bait balls, get well upwind of the school, shut off the outboard, and quietly drift into the area. A good shoal will often have dozens of bait balls with fish scattered in between. A good drift could be well over a mile long, and once you get past the productive water, slowly idle away and go around. Don’t ever idle back through the area you want to fish again.

There is also no reason to fish on top of someone. If you see someone hooked up, start your drift well upwind of them. You are in the right spot, you don’t need to be right next to them. If within 300 yards of other boats, idle very slowly, steering well clear of everyone else, until you reach the point where you will start your drift.

A little breeze helps the drift, but too much wave action decreases productivity. If the wind picks up or shifts, and you find yourself fishing white caps, hop over to the other side of the river and explore calmer waters. Should you decide to try another location, be mindful of other boats and keep a wide berth and avoid, if possible, running over shoals or schooling bait.

From June until the first big moon in October, wherever there is nervous water and flipping baitfish in the lower Neuse River and Pamlico Sound, giant red drum are likely to be lurking. Try the technique discussed, and hang on tight!