Ancient rivers carved deep canyons into the abyssal plain 10,000 years ago, when Earth’s water was trapped in massive glaciers, leaving sea level 400 feet lower than it is today.

Now those Ice Age river courses lie submerged as subaquatic canyons and seamounts. Where giant sloths and beavers once played, marlin, tuna, wahoo and dolphin have taken over. Offshore canyons bring pelagic species closer to shore, where anglers with the right strategy stand to score big.

Bottom Up

Lurking in the cold, dark water at the bottom of the continental shelf, huge grouper and tilefish, strange-looking barrel fish, and blackbelly rosefish haunt the steep cliffs and seamounts.

Capt. Joe DelCampo has made a study of targeting deepwater bottomfish. In his years fishing Norfolk Canyon off Virginia Beach, he has covered every inch of the bottom. “I have a map of the whole place in my head,” he says. DelCampo looks for blueline tilefish and sea bass in 50 to 100 fathoms. Over the 100-fathom line, on the steep canyon walls, he targets snowy grouper. In the deep, muddy flats, he finds golden tiles. DelCampo fishes as deep as 1,000 feet, where he catches his favorite fish, the blackbelly rosefish. Deepwater bottomfish are present year-round, but DelCampo favors spring and fall, when there are fewer annoying dog sharks.

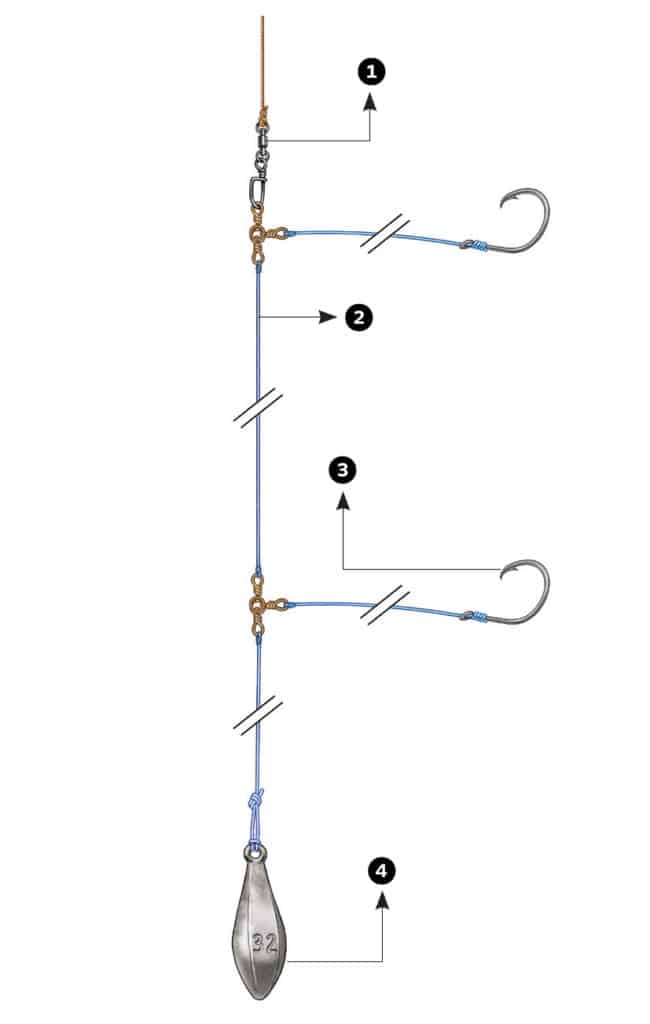

[2] 100-pound mono

[3] 8/0 hook on 12-inch, 100-pound dropper

[4] 28- to 40-ounce bank sinker on 50-pound mono, 12 inches below swivel Deep-Drop Bottom Rig

For blueline tilefish and sea bass, DelCampo uses 100-pound mono leader. For grouper and golden tiles, he steps up to 200-pound. A foot of 50-pound mono between the lower swivel and the sinker provides a break-off point should the sinker become snagged on the bottom. DelCampo chooses 8/0 circle hooks for bluelines and sea bass, and 12/0 circle hooks for grouper and goldens. Bluefish or albacore strips, cut into triangles, make the best bait. Pass the hook through the thick end to prevent spinning and tangling. Steve Sanford

“I rarely fish the same area twice,” DelCampo says. Instead, he looks for fresh grounds to find the best bite. “Bottomfish are eating machines; when they graze through one area, they move off to find more food,” he explains. DelCampo believes grouper and golden tiles are resident fish; when he pulls one or two out of a drop or hole, he leaves the area to prevent overfishing. “I’ve got a million marks out there,” he explains.

To find the fish, DelCampo switches on his fish finder’s bottom-lock feature and turns the gain up. He sets the machine to 200 kHz in water less than 400 feet deep, then switches to 50 kHz to go over the edge.

“I look for clouds of bait on the bottom,” he says.

DelCampo waits for calm days with a half-knot drift. “Bottomfish won’t chase a bait,” he says, so he kicks the boat into reverse to slow his drift. To keep his anglers from snagging the bottom, he drifts from shallow water to deep. He drifts up to a quarter-mile before moving to a new area. “Sometimes the fish are only 100 yards away,” he says. Other times he changes depth or location to avoid nuisance trash fish, like dog sharks.

SWS Planner: Deep-Drop Bottomfish

What

Deep-drop bottomfish

When

Year-round

Where

Virginia Beach

Who

Capt. Joe DelCampo

Capt. Cheryl

virginiabeachfishing.com

757-491-8000

SWS Tackle Box: Deep-Drop Bottomfish

Rods

6-foot heavy action

Reels

20- to 30-pound class, high-speed retrieve (6:1 ratio)

Line

50-pound braid

Leader

100- to 200-pound monofilament

Hooks

8/0 to 12/0 circle hooks

Bills and Eddies

Each summer, giant whirlpools of warm water swirl along the continental shelf like an escalator carrying schools of bait followed by voracious predators. On a satellite water-temperature image, these eddies look like dervishes of warm water that take on a life of their own. The water in the eddy could be several degrees warmer and noticeably clearer than the surrounding water. When an eddy sweeps over the canyon, the current is disrupted, giving the predators a chance to score an easy meal.

Fishing out of Ocean City, Maryland, Capt. Frank Pettolina intercepts these warmwater eddies as they pass Norfolk, Baltimore and Washington canyons. “We can follow a body of water for days as it moves down the coast,” he says. The challenge is predicting where the bait and marlin will congregate.

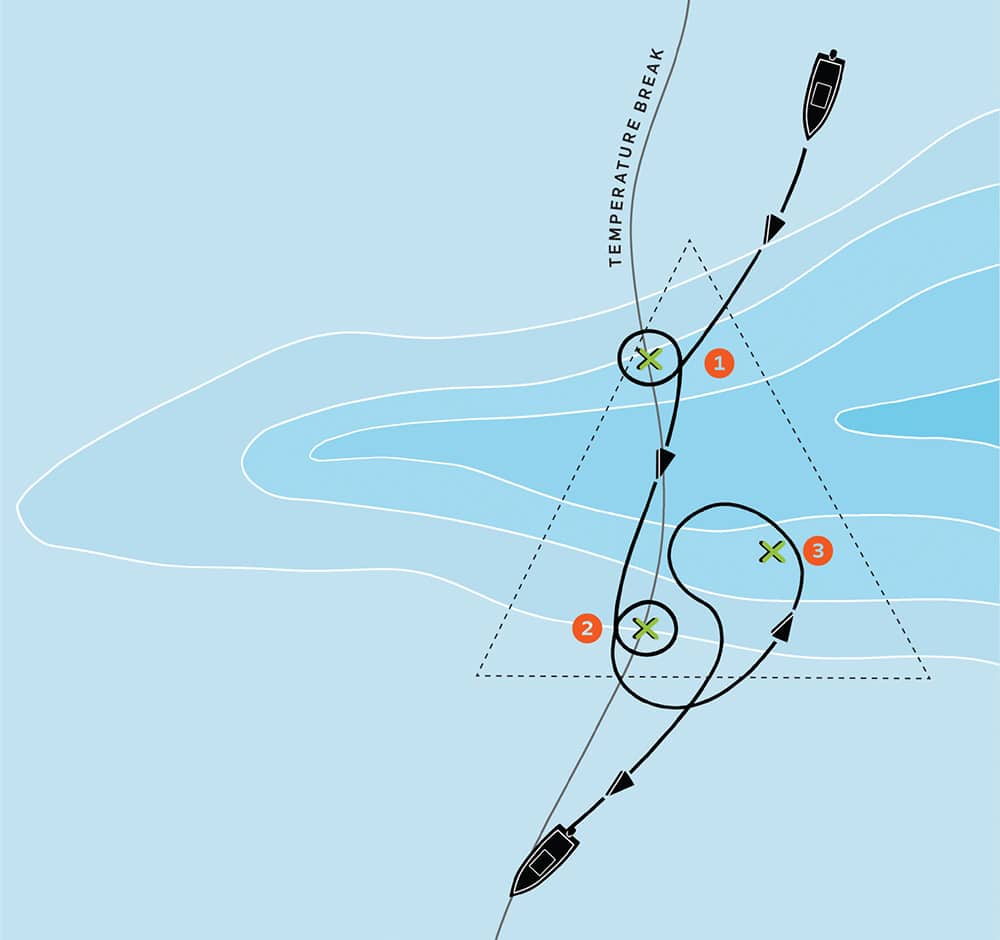

Pettolina says marlin season starts as early as June but really fires late in the summer. To start his day, he looks for a temperature break that crosses the canyon walls. These undulating bodies of water are in constant motion, traveling thousands of miles like a water-borne hurricane. As Pettolina fishes along the change, he pays close attention to how the body of water is moving. During the day, the break could move several miles inshore or push off. “I try to anticipate where the water is going and how that will affect the fish.”

[2] The second fish also hits at the temperature break.

[3] The third strike off to the side establishes the productive triangle. Capt. Franky Pettolina’s Marlin Pattern

To start the day, Pettolina looks for the edge of a warmwater eddy to cross the canyon. He trolls along the edge, zigzagging from warm water to cooler water and back. During the day, he notes which direction the water is moving and marks each marlin encounter on his chart plotter. When he has three marks, he works the inside of the triangle to find more bites. As the warm water moves over structure, schools of marlin will break away from the edge to hunt. Steve Sanford

Many times the fish will move with the edge, other times he finds them over structure or around bait.

To triangulate the best fishing grounds, Pettolina notes where he scores each marlin bite. “Any time I get action, I make a few circles,” he says. Then he continues along the break, marking hot spots on his chart plotter. “If I can get three spots that make a triangle, I’ll beat the hell out of that area.” He crosses the triangle from shallow to deep and north to south until he is certain that he has exploited its full potential.

Even when he’s not on the water, Pettolina is looking for marlin. Studying satellite water-temperature images and networking with anglers along the coast, the captain can track the movement of water, bait and billfish.

SWS Planner: Mid-Atlantic Marlin

What

Mid-Atlantic marlin

When

June through September

Where

Ocean City, Maryland

Who

Capt. Frank Pettolina

Last Call Charters

lastcallcharters.com

410-251-0575

Trench Warfare

Deep below the ocean surface, yellowfin, bluefin and bigeye tuna engage in a raging war over the offshore canyons and the continental shelf.

Each species claims a season and a section of the feeding grounds. Bluefins attack first in early May, then return in November. Yellowfins follow warm water through the summer. Bigeye tuna are an enigma, hiding around deepwater structure and surprising anglers at any moment.

Capt. Deane Lambros is in the middle of the fight. Fishing on Canyon Runner out of Point Pleasant, New Jersey, Lambros targets canyons from the Hudson to the Wilmington.

With hundreds of miles of water to cover, Lambros says water temperature and color are most important.

Bluefin tuna, he explains, seem to be more structure-dependent. “We catch them in the traditional spots,” Lambros says. When the ideal water moves over the top of bluefin hot spots, the bite turns on. “Bluefins tend to be on the flats outside the canyon,” he says.

Lambros often finds bigeyes at regular hangouts. Find a drop, plateau or seamount hosting bait and whales, and bigeye tuna are sure to be around. The fish often attack as a pack, knocking down several lines at once, causing chaos in the cockpit. He looks for bigeyes over steep drops inside the canyon.

Yellowfins are also around structure, but Lambros says they are more dependent on water temperature. He points out, “Most of the action comes around a temperature break.” But he admits that’s not always the case. Find a temperature break over structure and the tuna will usually be close by. He looks for blue or blue-and-green blended water. “I’ll fish the cooler side of the break if the water is clearer,” he adds.

Tuna don’t stop biting when the sun goes down, so Lambros specializes in overnight trips. “Sunrise and sunset can be the best fishing,” he says. After dark, the crew switches to drifting across the canyon while chunking butterfish. “I set up the drift to move through the best water and structure,” he says. “As long as I’m marking bait and fish, I’ll continue to fish an area.” If the area is devoid of life, he moves deeper or shallower depending on how the body of water is moving. If the warm water is pushing inshore, he might make a shallower drift.

“Canyon fishing is all about water and structure,” he says. As bait and predators ride the warmwater currents rushing along the continental shelf, they congregate in the deep canyons cutting into the coastal plain.

Local captains carry a map of the canyons in their mind.

“I don’t even need the chart plotter,” DelCampo jokes. He carries a mental picture of the bottom topography. For Pettolina, canyon fishing is a way of life. “I’m fishing tomorrow,” he says. “Can’t wait.”