Big fish lurk beneath coastal bridges, no matter the region. An angler casting a swimbait under a busy New York highway bridge; another dangling a chunk of crab in the pilings of the Chesapeake Bay Bridge Tunnel 400 miles south; a troller pulling plugs down a low-slung span in Miami; a guy on a skiff working a topwater along the gleam of streetlights on a Gulf Coast bridge: They all know the bounties that lie hidden at nearby bridges. Metro Bass Crazy Alberto Knie, who got his nickname by fishing the gnarliest locations in the worst conditions, believes the end justifies the means, especially when it comes to catching the biggest striped bass. To find monster stripers, he waits until nighttime and anchors under a bridge. He says the light falling from the street creates a shadow on the water, and that’s where the fish hide. “I see torpedoes cruising up and down the shadow line,” he says.

During winter, Knie waits until the flood tide brings bait to the bridge pilings. In the spring, the outgoing tide, which carries warmer water out to sea, is often better. “Striper action can be slow during negative feeding times, when fish are inactive and not feeding. But around a bridge, it’s almost never negative feeding time,” Knie says. “The fish are there to eat.”

Knie loves the chaos of bridge fishing. When the current drops out and the fish go on the feed, he expects to hook multiple big stripers. “Sometimes we have to release the anchor line and chase a fish through the bridge, but tackle needs to be stout to control fish around the pilings,” says Knie, who uses a variety of swimmers, darters, soft plastics and bucktails for bridge stripers. He insists that using large lures and heavy tackle allows him to catch bigger fish.

Chesapeake Bay Bridge Tunnel

Seventeen miles long with twin spans, a 90-foot arch, 5,000 pilings and two rock islands, the Chesapeake Bay Bridge Tunnel (CBBT) is one of the seven engineering wonders of the world, offering a lifetime of fishing.

The pilings and rocks of the CBBT hold a variety, from striped bass to redfish to flounder, but it’s tautog and sheepshead that get the most attention. Tog are active from fall through winter to early spring. Sheepshead take over in summer. These fish live deep in the structure, where they feed on crustaceans, so the first challenge is reaching the fish. It’s illegal to tie to the bridge pilings, so anglers use a wreck anchor made out of rebar to grapple the rocks and pilings.

Current is the key, and the best bite occurs during the turn of the tide. When the current is ripping, tuck into the eddies behind the rock islands. Once secured over the rocks or in the pilings, drop a live fiddler crab or chunk of blue crab into the concrete and granite.

The bite of a tog or sheepshead can be very light. To feel the nibble, pinch the liçne lightly, stay focused, and never take your eyes off the rod tip. Timing is essential because tog are quick to spit the hook. Lift the rod tip to the sky, crank down fast, and don’t stop until the fish is coming off the bottom.

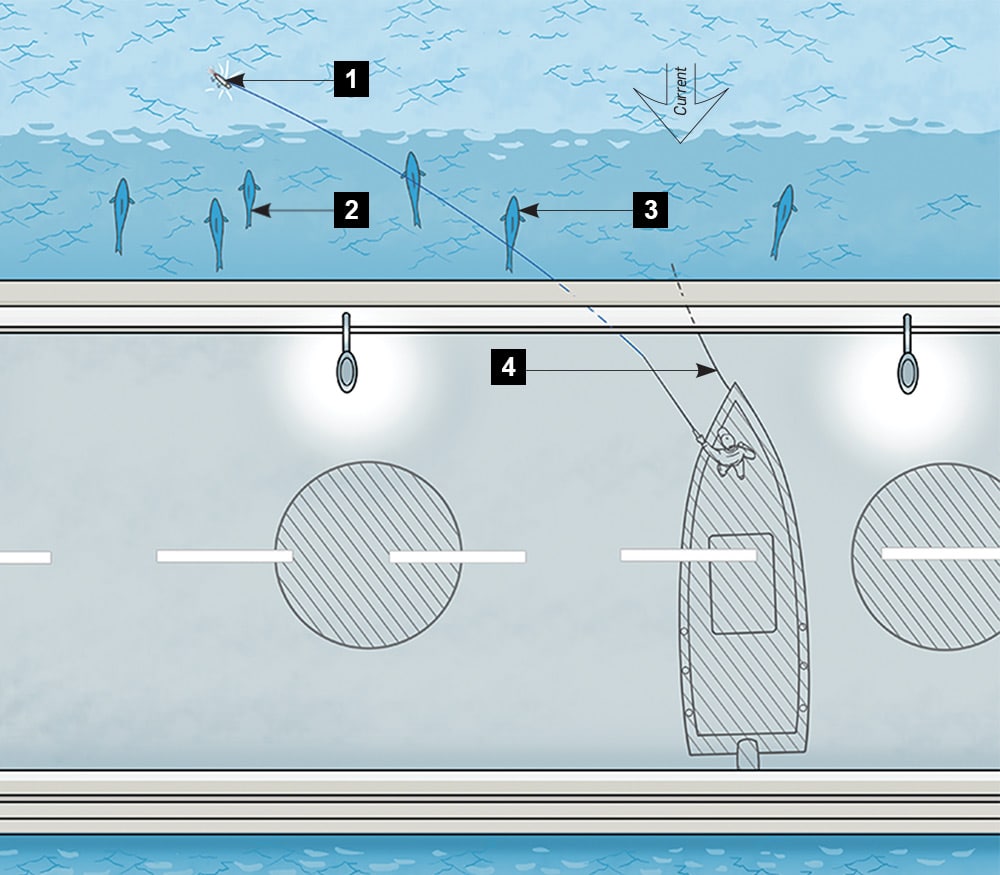

2.) Work lures down-current to the fish.

3.) Fish face the current in the shadows.

4.) Anchor under the bridge. Illustration by Steve Sanford

The most recent development in CBBT fishing is a fall run of big red drum patrolling the bottom around the bridge pilings and rock islands. Anglers bounce big jigs through the pilings or anchor up along one of the rock islands and fish chunks of cut spot or menhaden on a fish-finder rig. Jigging is best on the turn of the tide, while bait-fishing works better when the current is running.

The red drum that congregate around the bridge are some of the largest in the world. I’ve released fish over 50 inches long and 30 inches round, estimated at over 60 pounds. When drum get this big, they fight deep and take the angler around the boat. Getting just one of these bruisers boatside is reason to celebrate.

Miami Heat

“I live on an island,” Miami native Craig Hardie laughs, “so I’ve been bridge fishing since I was a kid.” To target big snook year-round, he trolls swimming plugs down the bridge span at night. “The weather is not as hot at night,” he points out, adding that the best action is in the wee hours. “When the traffic on the bridge dies down, the fishing seems to get better.”

Hardie rigs a medium-heavy spinning rod with a big swimming plug. “The lure should work 8 to 10 feet below the surface” he points out. In clear water, he likes a plug that has a black back and silver body. When the water is dirty, he prefers bright gold and orange.

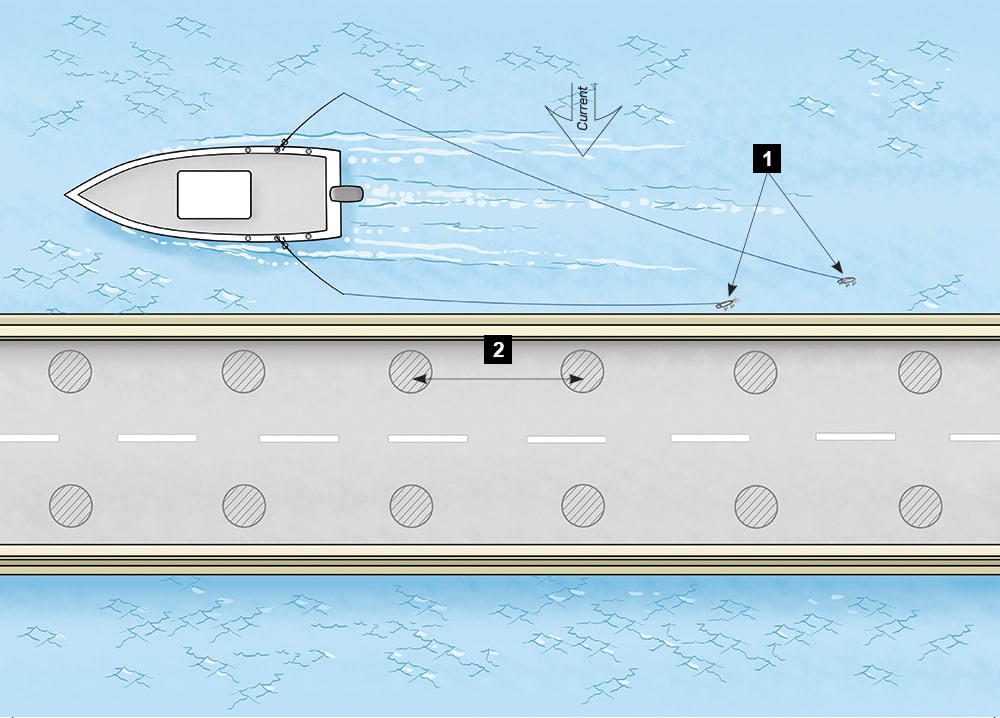

He trolls along the uptide side of the spans fast enough to make the lure dance. “Watch the rod tips vibrating to know the lures are swimming correctly,” he suggests. The best nights are on an outgoing tide. Hardie trolls close enough so the current causes the lures to bounce off the bridge pilings.

The best times of year are during the mullet and shrimp runs. The worst nights see the water choked with weeds. He offers this suggestion: “Put the rod tip in the water to catch the weeds, then lift the rod tip and the weeds fall off.” Even in choppy, windy conditions, the bridge still produces.

2.) Pilings Illustration by Steve Sanford

“When I hook a fish, I quickly turn the boat away from the bridge,” he says. A charging snook will take the line and expensive lure into unforgiving bridge pilings. Hardie laughs, “We’ve chased a lot of fish right through the bridge.”

Red Hot

As we race through the night in the cab of his pickup truck, Panama City Beach guide Nathan Chennaux remembers the night he discovered redfish under a local bridge. “My brother and I were fishing live shrimp on the bottom, and I could hear fish slapping the water,” he says. We’re on our way to fish the same bridge, and his story is getting me amped up.

Chennaux was in high school at the time. “I threw a topwater popper and hooked into a fish I couldn’t turn with 10-pound-test and a 3000-series reel.” After a tenuous battle full of cursing and deck dancing, he landed a 36-pound redfish. “Ever since, I’ve been under these bridges almost every night.”

We arrive to the bridge and find it unoccupied. A few minutes later, we’re casting large topwater poppers to the pilings and lights. In the dark, I can hear loud explosions of water. Every so often, I spot a big splash in the streetlights. “Cast into the blowups,” Chennaux suggests. “The reds hunt in gangs.”

I follow instructions. The next bowling ball that falls in the water, I land the lure a few inches away. One pump of the rod and another bowling ball falls on the lure. I’m hooked into a fat redfish in the dark.

We’re fishing in late April, and Chennaux promises the topwater bite lasts through early summer. As the water gets warmer in late summer, the fish respond better to midwater jigs and swimming baits. In fall and through the winter, the reds hang on the bottom and will take a big swimbait or jig. “I’ll mark them on the fish finder and make a drop.”

During the spring topwater bite, Chennaux waits for an outgoing tide. He’s noticed that the last two hours of the current are best. If there is a lot of grass on the surface, Chennaux says the slack current allows the grass to sink and makes fishing easier.

“First thing I do is shine a flashlight on the water and see what the fish are eating.” If he spots crabs, he ties on a loud topwater plug. When eels are on the menu, he switches to a Texas rigged worm or a long jerkbait.

On our night trip, Chennaux and I wait for the explosions before making a cast. When I comment that I could die happy night-fishing for reds, Chennaux says, “I’ve fished these bridges every chance I get, even on my day off!”