The 8-mile run across “the pond” didn’t take long on glassy seas. The sunny, calm conditions were perfect for spotting busting fish. After launching from Waterford, Connecticut, three of us crossed eastern Long Island Sound—a deep, tide-swept passage over a craggy bottom with no more than a ferryboat wake to navigate. Then whitewater appeared in the distance, on the uptide side of a rip, where such a disturbance doesn’t naturally occur.

“Albies!” Elliot Taylor yelled. He pointed off the starboard bow. “See the birds?”

“Got ’em!” I called as I pinned the throttle. “Hold on!” I urged to our other buddy, Sean Callinan.

A knot of terns pummeled the surface 300 yards away and, as we approached the rip, we spotted the metallic flash of porpoising predators. Powering down, I swung up-current of the froth and cut the motor a long cast away.

After my 4-inch Deadly Dick plopped among the commotion, I reeled a couple of turns and twitched the rod tip. I immediately felt a tug, and my spool whirred like a tire spinning in snow.

Then Taylor and Callinan hooked up simultaneously. Within moments, their lines crossed. Taylor ducked under Callinan’s rod and maneuvered around the bow with his rod bent double. Before long, another fish hit and parted Callinan’s line. Taylor and I pumped our little tunny up, and Callinan deftly unhooked them and slid them back into the water.

Albacore Alley

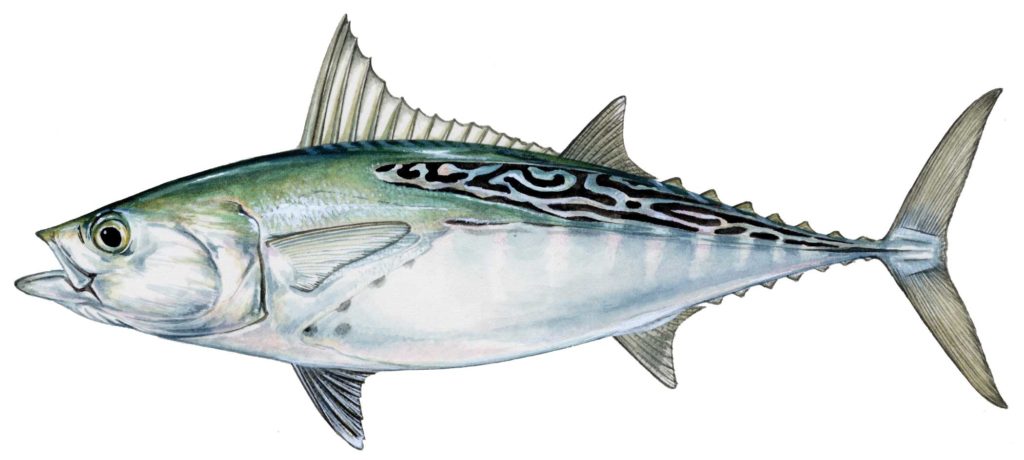

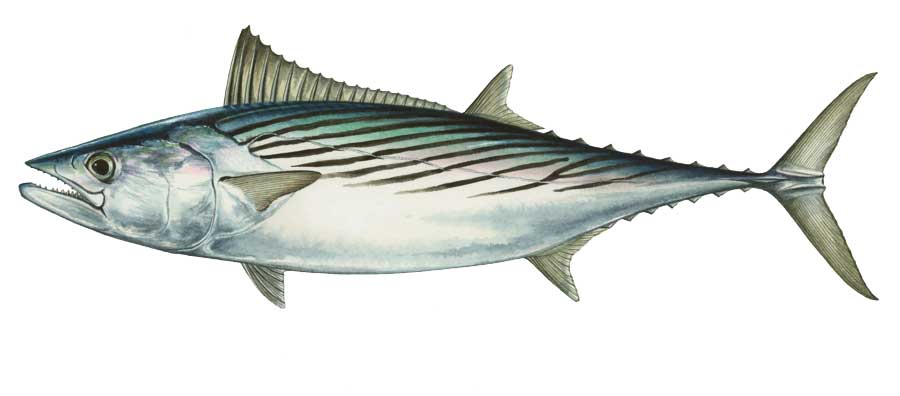

False albacore, nicknamed “apple knockers” by old-timers because they arrive when apples ripen and drop, are accurately named little tunny and were once considered a trash species. Now albies command devoted attention as prize light-tackle targets each fall.

Starting in early September and running through October, countless pods of apple knockers gather along the chain of islands at the mouth of Long Island Sound. This stretch of water, locally known as Albacore Alley, holds fish dependably each autumn while other spots remain hit and miss.

Between the islands, notorious tides rush, including the famous rips of the Race, the Sluiceway and Plum Gut, where bottlenecked waters surge upward from 300 feet to less than 30 feet in spots, creating turbulence that attracts albie forage. The hot action spreads as close to shore as Pine Island, only 100 feet off Groton, Connecticut.

On the Hunt

“Working birds are an indicator of albies,” says Ned Kittredge, a charter captain with 40 years experience, “but they aren’t essential. Many times the only sign is fish breaking. You have to look carefully. Their feeding behavior is different from bluefish, a result of their extreme speed. If you study them, you can tell the difference.”

Once you locate a pod, one option is to sprint to the school to make a quick cast or two before it settles or moves. But a fast-feeding cluster can top 30 knots, so this run-and-gun technique is most successful when large schools remain in one spot for more than a few minutes. Otherwise, schools tend to vanish just as you get within casting distance, only to have a group bust in the spot you just left. It’s this level of challenge that draws dedicated and patient action junkies.

Another plan of attack is a drift technique that involves cruising into an area of action and waiting, often uptide of a rip, or near a jetty or point, and letting a school come to you. Blind-casting as you wait often results in unexpected hits.

Many experts favor a fast retrieve as soon as the lure hits the water, which is productive most of the time. If the rapid return fails, make the lure an easy meal with a slower retrieve and stop-and-go action so the lure tumbles and wobbles.

“I like to approach up-current and off to one side of a school,” Kittredge says. “I position the boat to cast across and slightly up-current, and retrieve the lure at a moderately slow speed. With the engine off, the boat drifts into casting range in stealth mode. At times albies can be boat-shy, but when they’re feeding heavily, nothing bothers them.”

Match the Hatch

When albies cue in on specific prey, they’ll usually refuse everything but an exact imitation. “As selective sight-feeders,” Kittredge says, “their vision is impeccable. Little tunny key in on five bait species in the Northeast: juvenile squid, sand eels, silversides, bay anchovies and baby bunker, so it’s helpful to determine what they’re eating.”

Traditional lures are either flat and elliptical like ⅜- to ¾-ounce Kastmasters and Hopkins Shorty jigs, which imitate peanut bunker, small butterfish and squid, or long and thin metals like Deadly Dicks and Crippled Herring, which imitate silversides, anchovies and sand eels.

One problem with matching the forage is that a little, shiny lure is just one of thousands of small, shiny objects in a school of bait. Many albie pros think this mimicking of baitfish is the key to success. Others believe that an artificial that contrasts with the dominant prey gets noticed, so they switch to less traditional soft plastics.

Soft Approach

Ironically, many soft plastics look nothing like the tiny baitfish albies usually target. It’s the lure’s action that triggers an instinctive attack.

One key to successful soft-plastic fishing is using the lure unweighted to take advantage of its action as it twitches along the surface. The drawback is that an unweighted plastic doesn’t cast far on a breezy day. But when fish are hitting with abandon, a plastic with a small bullet head adds distance to your cast, and the fish still strike it readily.

Soft plastics come in a variety of shapes, colors and sizes. The standard 4-inch jerkbait-style lure, which imitates a minnow or squid, remains the most effective. Paddle tails are sometimes hot too. Because albies trap bait against the surface and key on the white undersides of prey, albino, pearl and white-and-silver are go-to colors.

Read Next: Little Tunny on Fly

Keep the soft plastic in good shape so it swims naturally. Replace any that have a bitten-off tail or have bunched on the hook. Top-rated soft-plastic hooks include super-sharp Gamakatsu and Owner Cutting Point models in a wide-gap, offset worm style with a black finish, in sizes 2/0 and 3/0.

The three of us had about 20 hookups and landed four or five fish each that autumn day, which is a good albie outing. But as the sun dipped into the western end of Long Island Sound, the tide and the bite quit, and it was time to run back to the launch.

“Well,” I said to the guys as I fired up the motor, “it doesn’t get better than that. Tomorrow’s forecast looks good. Are you free?”

“I’ll make myself free,” Taylor replied with a smile. “I wait the whole year for apple-knocker time.”

Tiny Tuna ID

SWS Planner – New England False Albacore

What: False albacore fall migration

When: Eastern Long Island Sound

Where: Mid-September into November

Who: These experienced New England pros know precisely where to find the albies:

Buzzards Bay

Capt. Ned Kittredge

watchoutfish@gmail.com

watchoutfish.com

Block Island Sound

Capt. Chris Willi

401-466-5392

sandypointco.com

Eastern Long Island Sound

Capt. Dan Wood

dwood@captdanwood.com

captdanwood.com

Western Long Island Sound

Capt. Chris Elser

203-216-7909

ct-fishing.com

Prospect or Pinpoint

False albacore are seldom picky but respond best to a lure that mimics the prevalent forage, at the proper depth in the water column.

Well-Stocked Tackle Bag

Surface feeders demand a different presentation than albies traveling below the surface. Match your lure to the situation.

SWS Tackle Box – New England False Albacore

Rod: 7- to 71⁄2-foot spinning, medium or light action

Reel: 4000 to 5000 series spinning reel with good drag

Line: 12- to 15-pound mono or 20-pound braid

Leader: 17- to 20-pound fluorocarbon; pros often avoid swivels and join the leader to the line with a double Uni knot or Blood knot