Trophy bottomfish have the advantage in a fight, at least initially. Whether it’s a double-digit blackfish on 20-pound braid or an oversize grouper on 50-pound or heavier tackle, one will eventually take you to the bottom. Usually, that’s the end of the game. But don’t fret, you still have some options to win the battle.

A few tricks have been proven to outsmart or “out-muscle” big fish, providing anglers with the chance to turn the tables. A sterling example occurred in June, when Daniel Delph and I ran 75 miles west of Key West to the Dry Tortugas. A light-tackle specialist, Delph suggested we use gear no heavier than 20-pound. Basically, we were going into Jurassic Park with slingshots. On our first drop in 250 feet, something huge devoured my pinfish. Using a spinning reel filled with 20-pound braid, a 40-pound fluoro leader and a 4/0 3X-strong hook, I couldn’t stop the fish; it powered straight to the bottom and rocked up. It wasn’t budging either. Enter trick No. 1: free-spool mode.

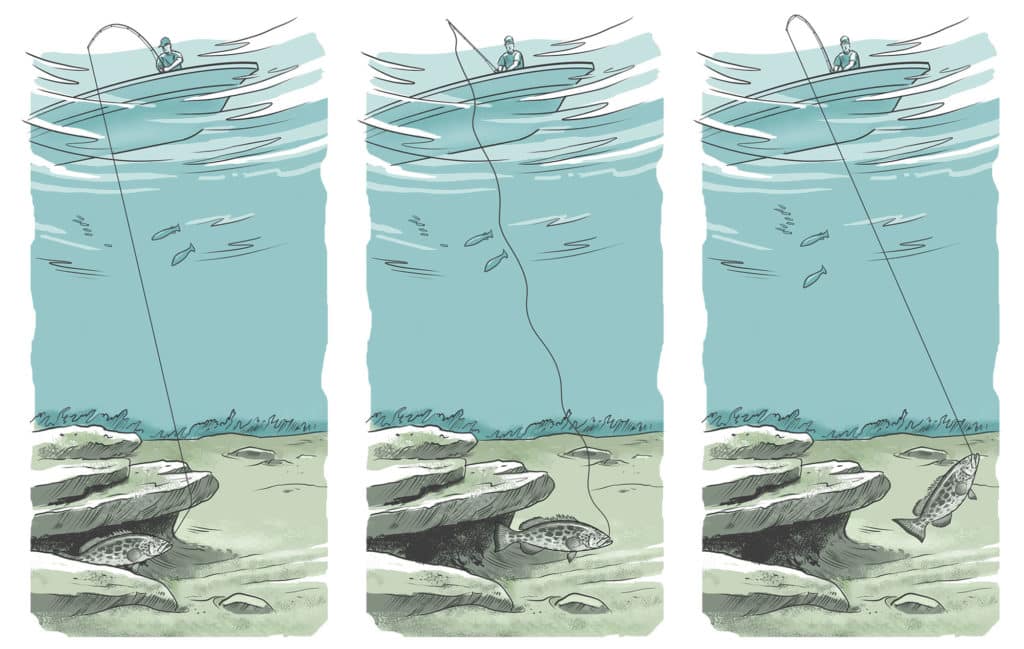

Let It Flow

I continued paying out braid while Delph stemmed the current and held the boat in place. The objective of free-spooling is to relax the pressure on a fish, until it believes it’s safe to leave its shelter. It’s not always a quick process. A crucial subtlety is the ability to monitor the slack line for hints of a fish leaving its temporary hideout. When detected, close the bail, wind tight, and rapidly stroke the fish to get it off balance and coming your way. Doing so earned me another shot at my quarry, albeit short-lived. Yes, it rocked up again.

“A fish isn’t comfortable holed up like that,” Delph says. “It’s in there with its gills and fins flared, trying to stay in the reef, and it’s getting pretty beat up. It wants out as much as we want it to come out. So, patience is a must. Beating such a fish often comes down to waiting it out. Sometimes you wait 15 minutes or more in free-spool for that opportunity.”

I had a third chance at this fish, but it was still too powerful. After gaining 20 feet of line or so, back into the bottom it went. Ironically, I got a fourth opportunity several minutes later. I gained more line than before and battled the fish a bit longer, but it managed to reclaim its hold. As precious fishing time evaporated, I seriously thought about breaking off the fish. But when Delph hooked into a red snapper, I put that thought on hold and placed my rod in a holder to assist.

During the fight, the boat drifted from the hookup spot. Some 10 minutes later, while we were releasing the snapper, I heard line leaving a reel; it was from my spinner. Apparently, the angle of the boat drift and drag pressure pulled my fish into open water. After four attempts, we finally boated a 55-pound black grouper. Talk about a well-earned catch. The key points here: patience—we spent some 45 minutes on this grouper—and subtlety, noting the slightest difference when paying out line, which indicates a moving fish.

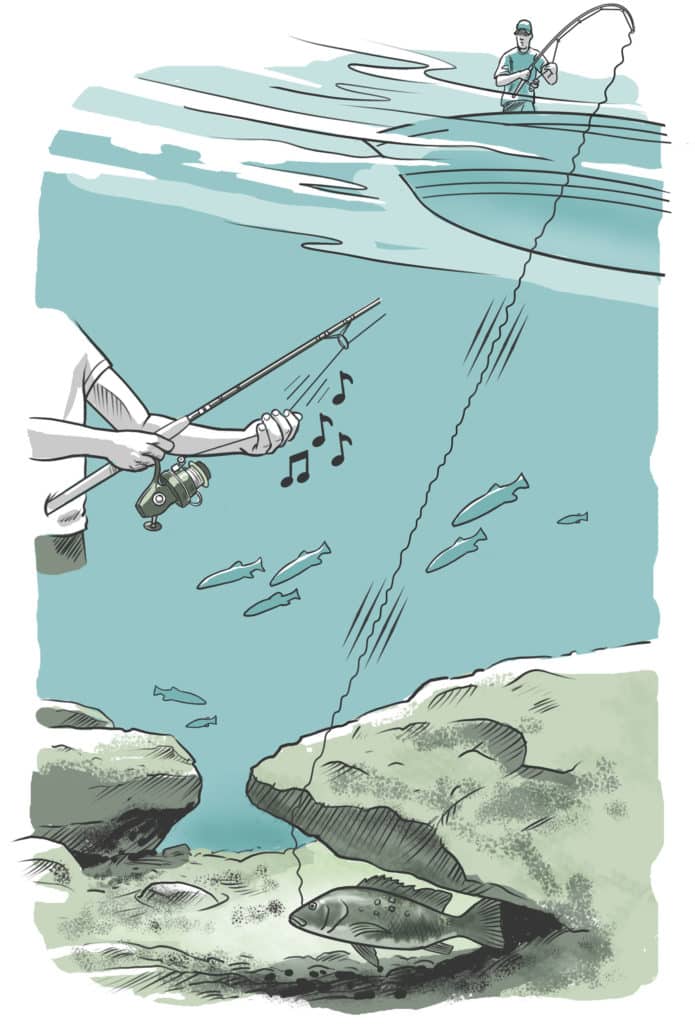

Banjos Please

As odd as it sounds, vibrations from strumming braid and even mono lines frequently irritate a rocked-up fish into fleeing. I actually tried this twice on my big grouper, but it didn’t work. However, the tactic has paid off for me numerous times, most recently with a cubera snapper that swam into bottom debris.

Free-spooling didn’t work, so I came tight and strummed the 80-pound braid for a few minutes. Braid especially telegraphs vibration to a hooked fish, which senses it through its lateral line. I’m guessing that between the stress of being holed up and the irritating vibrations, the fish panicked and fled its sanctuary. That move was just enough for me to get it off balance, play it to the boat, and register a release.

Four months after that cubera trip, we dropped baits around a Key Largo wreck in 220 feet. Kevin Tierney hooked up on 20-pound spin tackle, but the fish dived into the wreck. Free-spooling didn’t work, so Tierney came tight and strummed the braid. Within a minute or two, the fish exited the wreck, and he landed a daytime cubera.

“There’s something about it that makes fish want to leave their holes,” says Capt. Kevin Jeffries, a Key Largo reef and offshore guide. “We’ve often relied on ‘guitaring’ braid to force cuberas out of wrecks and structure.” Jeffries takes the strumming trick one step further. “I’ll come real tight to the fish, strum the line a bit, then quickly free-spool. When the noise and pressure cease, the fish thinks the threat has gone. It sometimes reacts by instantly swimming away.”

Define Your Angle

Idling back to a rocked fish is the last-ditch effort. You just guess the location of the structure and the angle at which the line exits. On the initial attempt, ease over the top of the hooked fish, come tight, and apply heavy pressure.

Beth Synowiec from Virginia Beach, Virginia, is a master at scoring double-digit tautog and golden tilefish. “When a big golden tile makes it back into its burrow, there’s an excellent chance of losing it,” Synowiec says. “However, I’ve had good results by getting above the fish and maintaining the line taut. The trick is to periodically lift the rod suddenly in an attempt to pull the fish out with no warning. It’s a waiting game that depends on surprising the fish with a sudden, unexpected rod sweep to catch it off balance and pull it from its burrow. This occurs in depths approaching 900 feet, mind you.”

Another option: Determine the angle at which the fish entered the structure, position the boat along the line of pull, come tight, and apply pressure. The boat can also help by powering it away from the structure. But if the angle is incorrect, you’ll feel line and leader dragging across the structure, and it will fail. “I’ve managed to save a fish or two going this route when all other tactics have failed,” Jeffries says. “If this doesn’t work, well, it’s probably not your day.”

Fish Smarter, Not Harder

Having a big fish rock up is a heartache, and in many cases, inevitable. But don’t give up after a few retaliatory tugs. Be smart and counter with the tactics outlined above. Had I given up after that 55-pound grouper rocked me for the second or third time, you wouldn’t be reading about it now.