Full disclosure: With regard to the outboard on a project boat a friend and I are working on, we screwed up big time. We wanted an inexpensive fishing skiff to hunt redfish in the shallow sections near the St. Johns River in Jacksonville, Florida, and found a “cheap” Pro Sports 18 Flats with a first-generation 2002 Yamaha F115. The boat needed work, but we loved its wide-open spaces and relatively wide beam. My experience with Yamaha outboards has been excellent. When properly maintained, they are reliable and can last a long time. But as Yamaha likes to say, maintenance matters. Unfortunately, the guy we bought it from had no maintenance records because he wasn’t the original owner and hadn’t owned it for very long. That was the first red flag.

Learning the Hard Way

My co-owning friend knew a mechanic who looked it over and pronounced it worth the money. We learned the hard way that the first rule of used-boat buying is to make sure your mechanic friend knows what he is doing. As it turns out, he was better at rigging than correctly diagnosing and fixing problems.

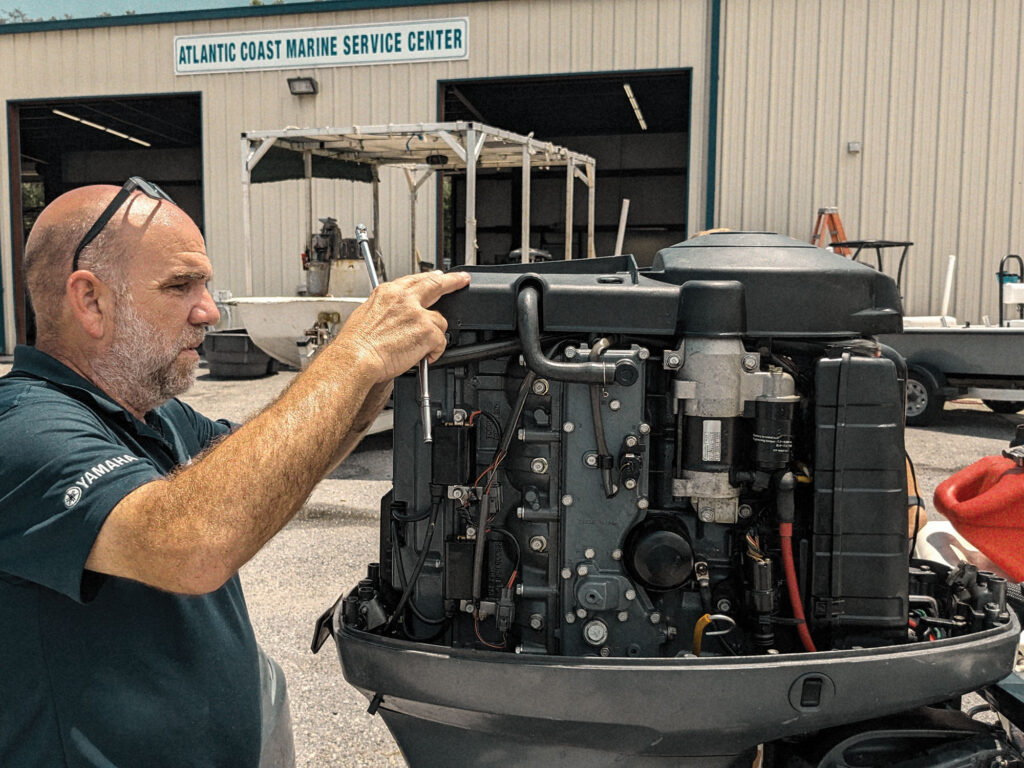

Although the engine seemed to run fine initially, a series of cascading maladies began soon after we bought it. According to our mechanic, we were always one part away from being good, but the cost mounted quickly, and it seemed like we were building a new motor one part at a time. Finally, the powerhead started leaking oil, and we did what we should have done long ago: We took it to a local Yamaha Master Technician, Brett Elrod at Atlantic Coast Marine, for his appraisal. After checking it out, his opinion was short and not so sweet. “It’s not worth fixing,” Elrod said. He tested the compression, and it was low. The wiring harness was bad, and that was before addressing the oil leak. “I estimate it will take at least $5,000 to get it running, and at the end of the day, it will still be a 22-year-old engine,” he surmised.

So, what are the telltale signs an engine is too far gone to make fixing it a viable option?

Inspect the Lower Unit

Start with the lower unit. Is the skeg tip broken or bent? Physical damage to the lower unit could go deeper than just what is visible. Hitting the bottom can damage the gears or shafts. Look for trouble signs such as balky shifting. Not long after we got the F115, it refused to shift into reverse, so replacing the lower unit was our first big hit. That should have been our first sign to get the parachutes on and bail out of the proverbial airplane. Inspecting the gear lube more closely could have given us a hint of things to come. “Take a look at the gear lube in the sunlight,” Elrod says. “If it shimmers, those are tiny metal shavings produced by grinding gears.”

Read Next: 10 Common Solutions for Boat Engine Problems

Take a Test Ride

One of the best indicators of the a motor’s health is its performance, and it’s vital to get a baseline by doing an extensive performance test while it’s running well, including top speed and fuel-economy numbers. While our motor initially ran a little rough, it pushed the boat into the low 40s, which seemed about right. But it wasn’t long before it struggled to get on plane. When performance starts waning, it could be the cylinders losing compression, the electronics failing, or a fuel-delivery issue. Taking a demo is a good idea when considering a used engine. “If the owner will take you out for a demo ride, that’s a good sign that the outboard operates as advertised,” says Ben Garrison, Atlantic Coast Marine’s 5-Star service manager.

What to Look For?

So, what does a professional prepurchase inspection look like? “We start by plugging in our diagnostic computer to see if there are any problems, like a cylinder that isn’t firing,” Elrod says. “Then we put the lower unit under pressure. If there’s a bad seal, it will leak. We look at the gear lube and motor-oil color and condition.” Good oil does several things, such as conditioning gaskets to keep them pliable, he explains. This was one of the issues with our motor—the head gasket had grown hard and brittle and lost its seal, causing an oil leak.

“We also look for corrosion,” Garrison says. “Dissimilar metals or poor maintenance can cause corrosion. One telltale sign of trouble is if you take the cowling off and there’s water dripping. Any moisture that gets inside can cause problems.”

“Professionals also test the compression in each cylinder,” Elrod points out. “If compression is low, it can mean the rings are bad, but it can also be something like a carbon buildup, which we can fix by cleaning it out.”

New motors have advantages, like better diagnostic information from the onboard computer. Yet, modern electronic control modules are also far more sensitive to voltage variances. “With today’s motors, it’s vital to have the correct-size battery, and ensure the cables are properly connected and the battery is in good shape because fluctuations in voltage can cause damage,” Garrison explains.

My boat partner and I are looking for a different outboard and haven’t ruled out buying a new one. If it’s used, be assured it will receive a full prepurchase inspection from a qualified mechanic.

One thing is certain: We’ve spent the last penny we are going to on that old one.