Like real estate, reef and wreck fishing are all about location, location, location. Being able to set the anchor so the boat is positioned properly means the difference between having an epic day or going home with a big goose egg.

But when the time comes to move to the next spot or return home, getting that anchor back aboard quickly and efficiently is also important. For your back’s and muscles’ sake, you want to retrieve the anchor with the least amount of physical exertion. If your crew doesn’t include a couple of strapping offensive-lineman types, here are some ways to easily accomplish the task without self-inflicting bodily harm.

For boats equipped with a windlass, be it electric or hydraulic, deploying or retrieving the anchor seems as simple as mashing a button. But a windlass is designed only for assistance, says Alex Mansito, OEM powerboat sales manager for Lewmar, maker of several windlass models, including the Pro-Fish series, designed specifically for reef anglers with a free-fall function that allows quick anchor deployment.

“No matter which windlass you’re using, start by figuring out the current and wind direction to determine how the boat will rest in relation to the reef,” Mansito says. “The more chain you have for ground tackle, the better. We recommend at least 25 to 30 feet. The heavier chain falls faster than the rode, creating a bow that allows the anchor to settle. Once it does, cleat it off and back the boat down to set it. You can always let out more rode to improve your position on the reef. Before you start fishing, though, make sure the anchor line is cleated off. Don’t let the windlass take the brunt of the waves and the boat’s pitching, or you’ll wear it out prematurely.”

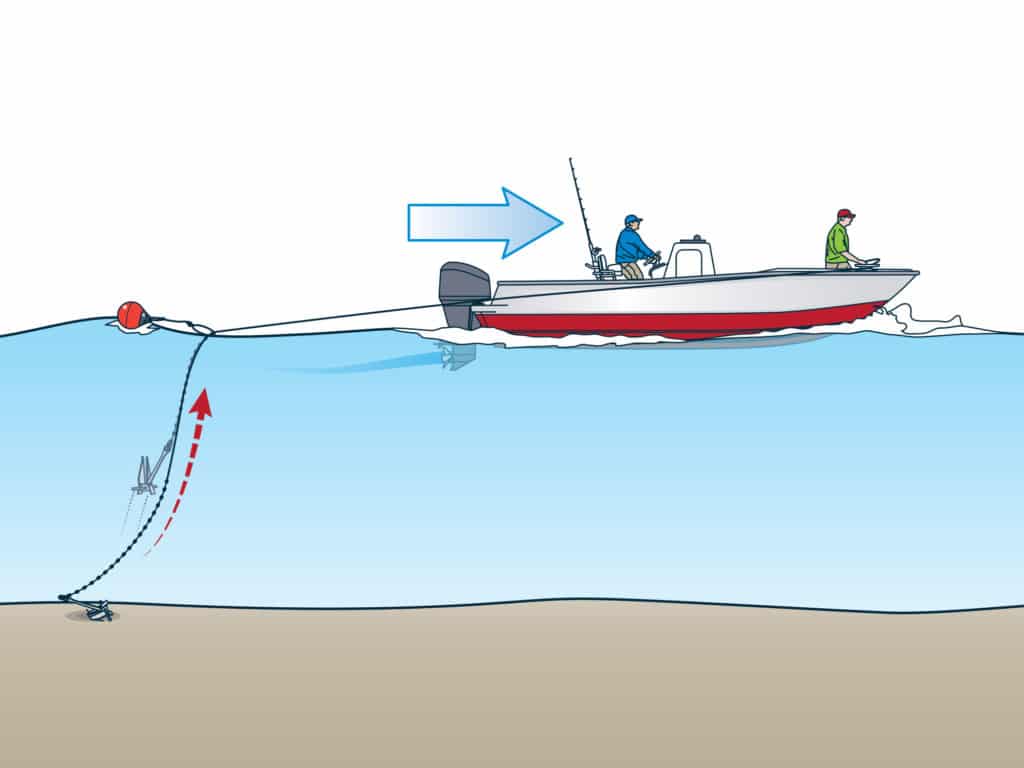

For retrieving the anchor, Mansito recommends idling the boat forward to recover as much rode as possible to remove slack. Then use the windlass to pull the anchor straight up. If the anchor is stuck, use the boat engines to power it loose, making sure the rode is cleated off first. A release setup to pull the anchor in reverse helps. Once the anchor is off the bottom, use the windlass to retrieve the remaining rode and chain. “Gravity feeds the windlass rode, so always wash it down with fresh water after using it,” Mansito adds. “If the rode gets stiff, soak it in some fabric softener before rinsing. That will make it supple again so it lays better in the anchor locker.”

There’s another less expensive yet effective way to recover the anchor without straining your lower vertebrae. Capt. Skye Stanley, who has been running charters in Islamorada, Florida, for the past nine years, says he and his mate use a release-ball system to pull the anchor — as many as eight times per trip — even when fishing shallow patch reefs in 20 feet of water. “Why not use one?” Stanley asks. “I call it the Mate Saver 2000. It’s simple, quiet, and it really saves my mate’s back.”

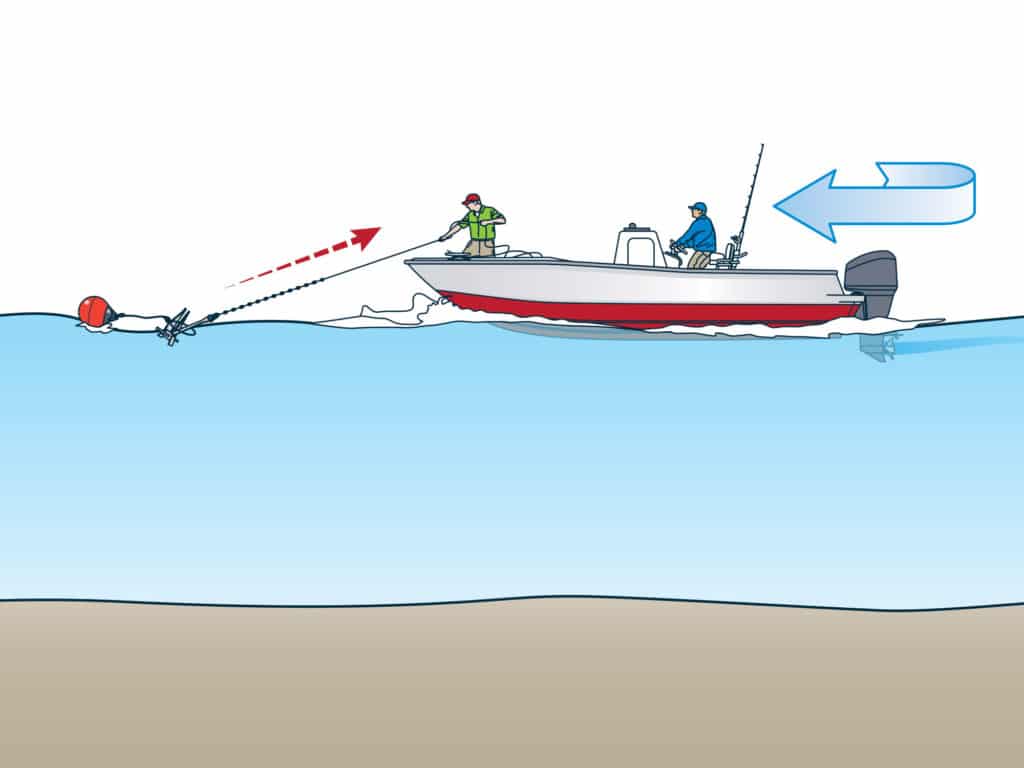

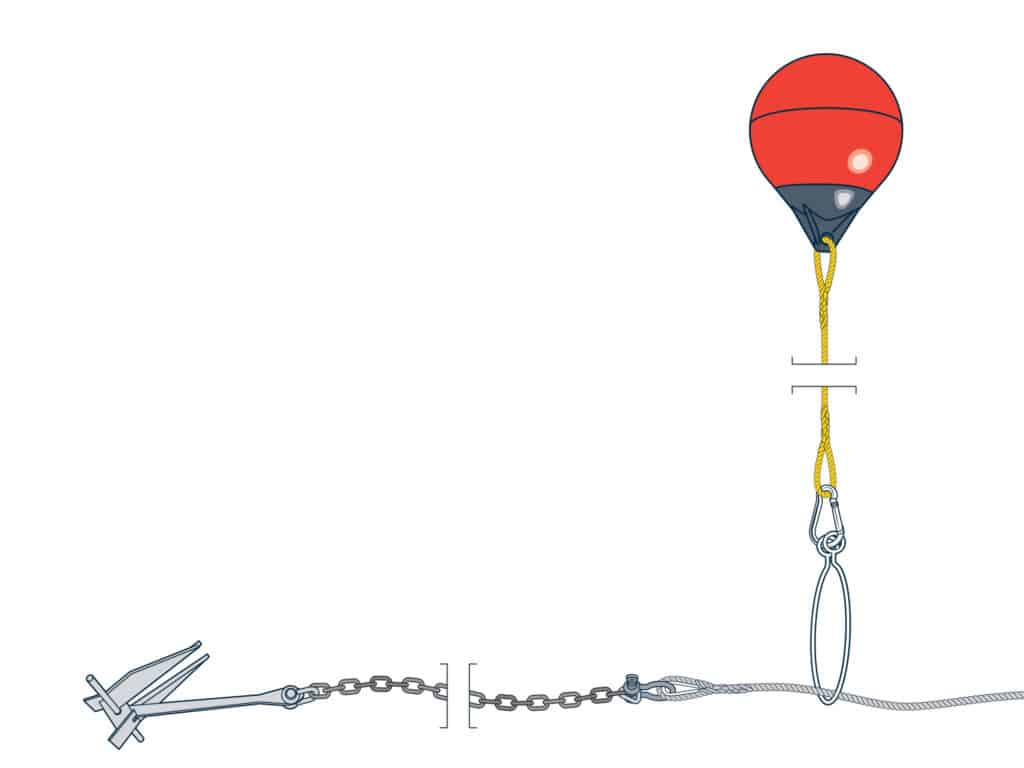

Stanley’s setup includes a 22-pound Bruce anchor with 18 feet of heavy galvanized chain. His release-ball rig includes a medium anchor ball (a round Poliform or vinyl buoy, about beach-ball size) with 1½ feet of nylon rope eye-spliced to the ball on one end, and a stainless carabiner clip on the other. The splices are wrapped with tape for a smoother transition. A 10-inch stainless anchor-retrieval ring is then slipped around the anchor rode and snapped shut with the carabiner, completing the rig.

“I steer from the port side, so I throw the ball off that side to keep an eye on the anchor rode and ensure it stays clear of the engines,” Stanley explains. “As I idle forward, the ball slides down the rode, changing its angle, and the buoyancy of the ball dislodges the anchor and pulls it straight up to the surface. Then I just turn the boat away from the rope to keep it out of the props.” Once the ball is on top, Stanley steers toward it, taking advantage of the slack to retrieve the anchor rode and coil it in the anchor locker. If the ball is down-sea, he idles up-current before shifting the motors to neutral. The boat then drifts toward the ball as the anchor rode is recovered.

This anchor-retrieval system was borrowed from commercial fishermen, who for a long time have used a similar rig to quickly and effortlessly retrieve crab and lobster pots.

For smaller boats or shallower water where anchoring requires no more than 15 feet of chain, there’s one more option. The AnchorLift, a variation on the release-ball rig, is a gizmo that works on the same principle as a mechanical ascender, a piece of equipment used in rock climbing and rappelling that allows rope to pass in one direction while a sliding lock keeps it from backing out.

Like the release-ball rig, the AnchorLift is used in conjunction with a vinyl buoy or Poliform ball, but it replaces all hardware and also negates the need for connecting nylon rope with eye-splicing. It does require that you run the bitter end of the rode through it before dropping anchor; other than that, all the steps in the anchor-retrieval process are the same.