Different fly lines impact not only your casting, but also your fishing overall. Every fly-rodder should, therefore, understand the basics of line design and learn what to look for when selecting a fly line that best suits his or her needs. I’ll limit this discussion to floating lines.

CORE VALUES

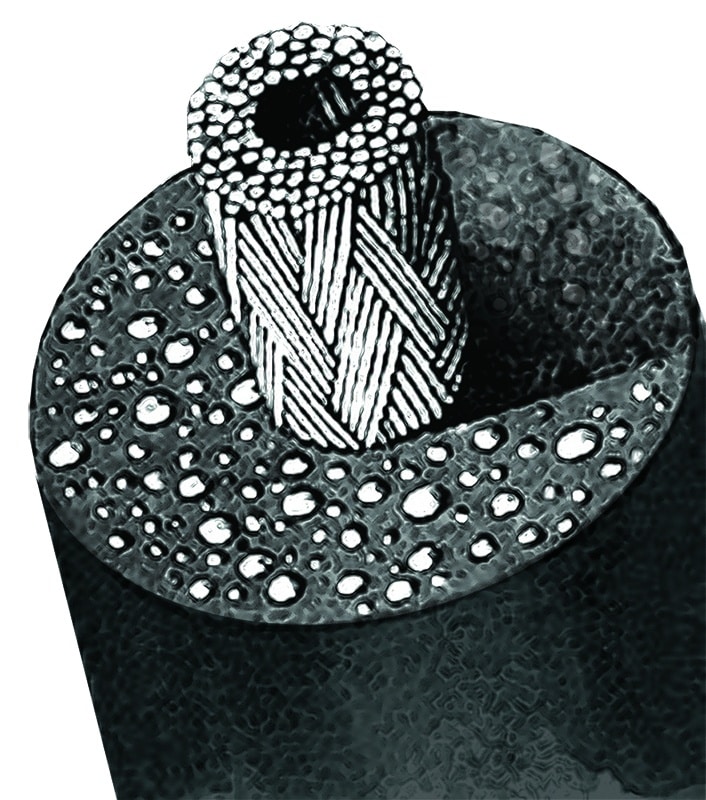

A fly line comprises two components: the core and the coating, and both can affect the casting. Cores made of the stiffer single-strand or braided monofilament are used for warm water. They keep a fly line from wilting and becoming excessively limp in tropical climes, but they tend to develop memory and resist stretching in cold weather. That’s why braided nylon or Dacron cores, more supple in cooler temperatures, are most commonly used for cold water lines. The slickness of the coating, be it smooth or textured, is also important; so is the substance used for the coating — polyurethane, PVC or co-polymer — which can affect a fly line’s stiffness. In that regard, however, the core material generally is more critical.

AVERAGE PROFILE

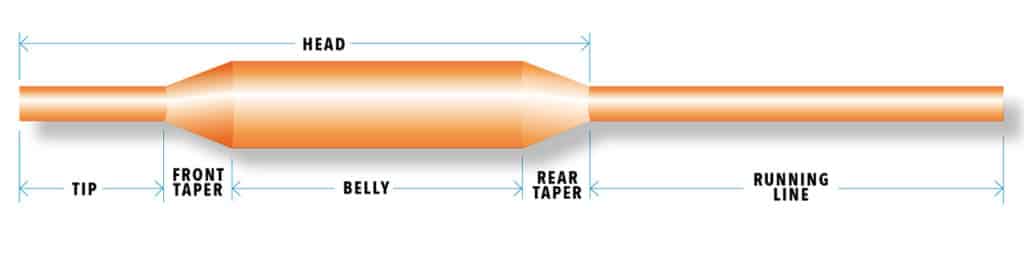

A line’s profile — the way it is tapered at different points — can be paramount to its performance. The tapering is controlled by making the line’s coating thicker and heavier, or thinner and lighter at various points. Although some manufacturers may opt for more complex schemes, in its simplest form, a weight-forward (WF) saltwater fly line has a short level-tip section (12 inches long or so), to which you attach the leader. Then comes the “front taper,” a 3- to 10-foot length that steadily widens as it transitions into a thicker “belly” section, a 20- to 30-foot stretch that carries most of the fly line’s weight and energy. At the back end of the belly, the “rear taper,” a 5- to 15-foot length, decreases in thickness as it leads to the long, thin “running line.”

LIMITING LABELS

The front taper, belly, and rear taper comprise what is known as the “head” of a fly line. The belly can vary in thickness and length, and the front and rear tapers can be longer or shorter. Shorter-head lines — those featuring shorter, thicker bellies and steeper front and rear tapers — are varyingly labeled as saltwater, flats, bonefish, tarpon, redfish or striper lines — but all are variations on a theme. You don’t need a line for each species. Base your line selections on casting and fishing requirements, regardless of the name or the target quarry.

BASIC NEEDS

Since shorter, steeper front tapers turn over faster, a fly line with that configuration is well suited for throwing larger and heavier flies. Lines with more gradual tapers release energy through a longer turnover, so they provide more delicacy and are more suitable for smaller flies. The rear taper helps to control the outgoing line, making it easier to mend while in the air and on the water. Therefore, lines with longer bellies, or those with shorter bellies matched to long rear tapers, afford better control during the cast.

MIND YOUR HEAD

When selecting a new fly line, focus on the total length of the head. For shorter casts, quick rod loading, snap casting, and for tossing heavy or air-resistant flies, select a line with a steeper front taper, a shorter, heavier belly, and shorter rear taper. If you will be casting long distances or if you’ll require more delicate presentations, opt for a line with a standard or longer head, i.e., a longer belly with longer front and rear tapers.

All the foregoing may sound daunting, but it’s not that hard. The next time you visit a fly shop, consult the manufacturer’s information inside or in back of the box to review a line’s profile before you purchase. Pay special attention to the length and tapers. It makes all the difference.

TALE OF THE TAPER:

Fly Line Construction

RIO Mainstream Saltwater

AIRFLO COLD SALTWATER