Locked behind a wall of repressive and often brutal dictatorship and isolated by global politics for 50 years lies not only an engaging history, culture and people, but a look into the past — and hope for the future. Equally engaging, fishing in Cuba offers an opportunity to rediscover a long-inaccessible piece of our own heritage and legacy as anglers.

Bonefish tailed in the shallows on all sides as we poled among the islets. Once our guide had us in position, my partner Bo Jackson took the gun seat for the first cast. He dropped the fly gently between some mangrove shoots, where a fish took it without hesitation. Scarcely 20 minutes from the dock, we had our first bonefish, on a flat that appeared to have never been fished, pocked with the tails of laconic fish that acted as if they’d never seen a fly.

That was our arrival day warm-up in Jardines de la Reina, the Gardens of the Queen, a 100-plus-mile archipelago known to anglers simply as JDR, located on the northern rim of the Caribbean, some 60 miles off the southern coast of Cuba. We’d been awhile getting there: a 4 a.m. start in Havana followed by a six-hour bus ride through verdant forests and sugar-cane fields that seemed to take us back in time. We shared the road with modern Chinese tour buses, horse carts and Soviet-era motorcycles. We drove through Ciego de Avila and south to Jucaro on the coast before finally hopping on a boat for the three-hour run to La Tortuga, the floating lodge operated by Avalon, an Italian company in partnership with the Cuban government for nearly two decades, that holds exclusive fishing and diving concessions to this and four other prime locations in Cuba.

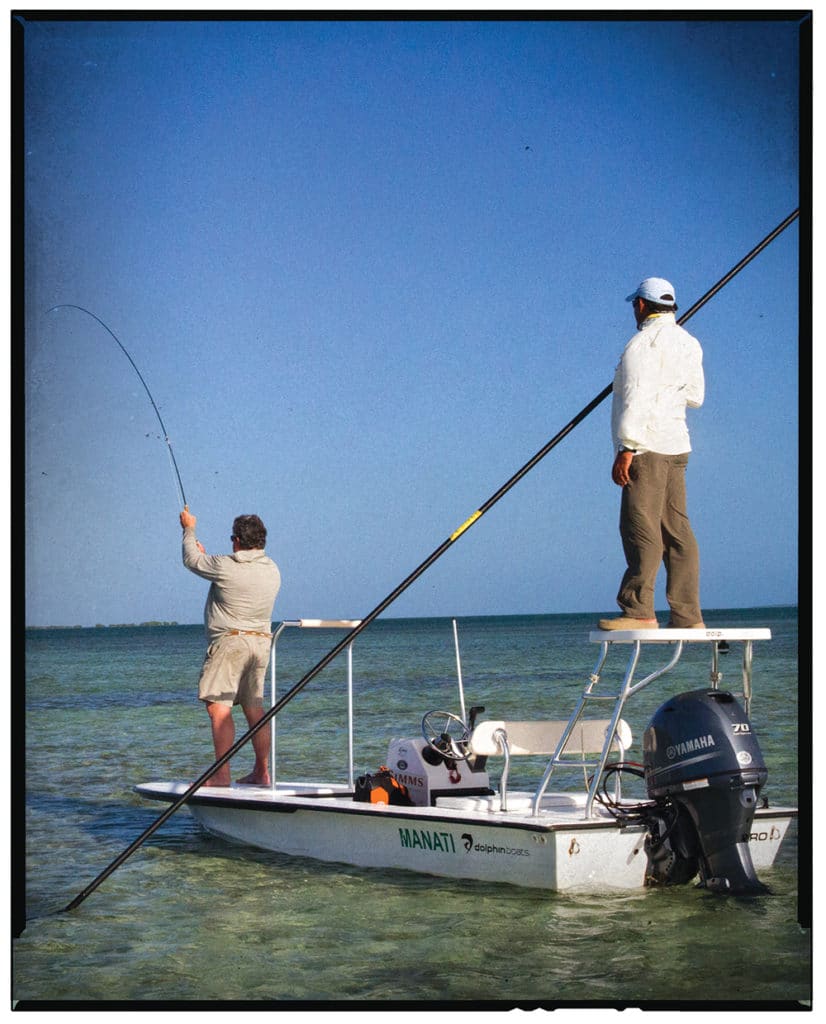

To appreciate this chain of islands and the surrounding flats, imagine the Florida Keys uninhabited and off-limits to commercial fishing. Then site a modest, full-service floating lodge in a secluded mangrove creek, with a fleet of modern skiffs with unlimited fuel allowance and captained by expert guides. From La Tortuga, just a dozen anglers a week get to fish a sprawling 50-mile stretch of keys and shallows. During our visit, we never shared a flat nor saw another boat on the water.

Slam Quest

We each caught a couple of bonefish that first evening while Bemba, our guide, sized us up. We must have passed muster, for as we headed in for dinner, he announced, “Tomorrow we go for permit!” The next morning, we hit the bonefish flats first, partially in response to the stage of the tide, but mostly because from day one, JDR guides focus on getting their anglers a grand slam: bonefish, tarpon and permit on the same day.

The plan is to catch the least-demanding fish first — in this case, bonefish, which are so reliable that many visiting anglers (Europeans have been fishing in JDR for nearly 20 years) who have never fished for bonefish, or ever fly-fished, find success with both on these flats.

Though occasionally someone lands a 10-pounder, the bones we encountered weren’t huge, running up to a respectable 5 or 6 pounds. But wherever we found them, when the tails went up and the fly hit its mark, the fish pounced on it. Both fishing from the boat and wading barefoot on the clean sand bottom, we tallied 10 fish before moving on.

Next Up: Tarpon

Midmorning found us just inside a wide breach between islands with the tide pouring from the Caribbean into the Gulf of Santa Maria. Bemba moved us onto a broad flat where a 6-knot current bent the lush turtle grass blanketing the bottom toward the north. A few minutes on the push pole lined us up on a pod of tarpon cruising along in 3 feet of water.

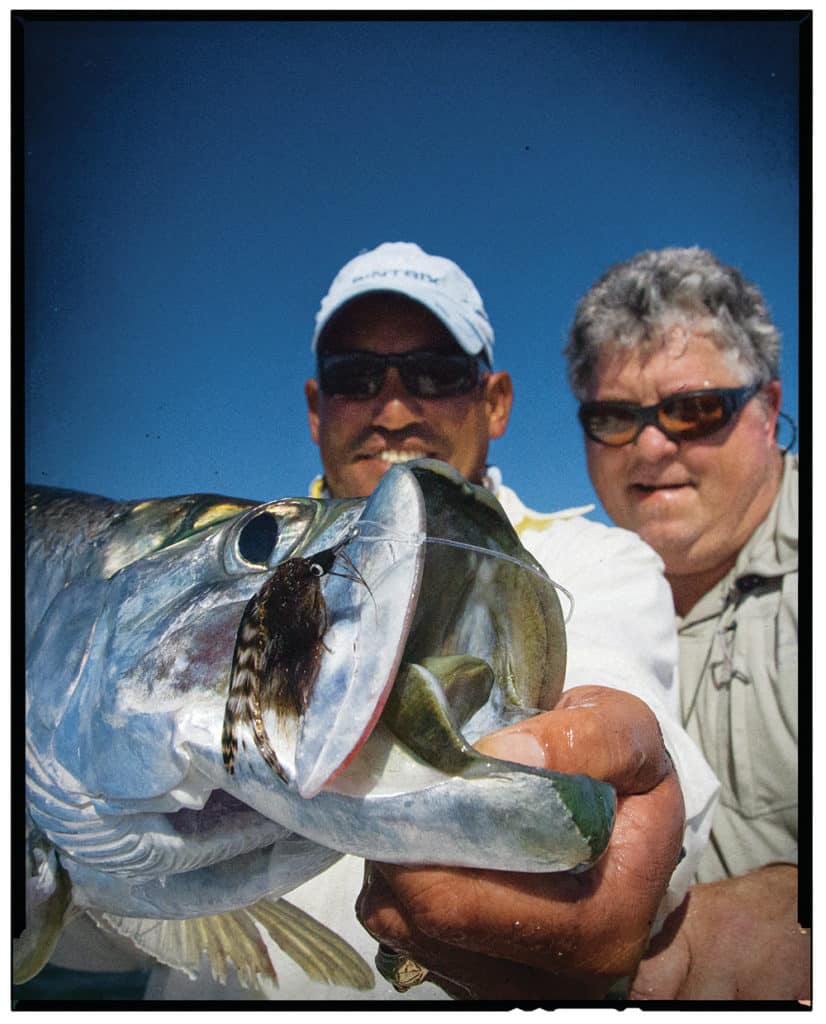

Tarpon are usually more challenging than bonefish, but these fish were just as willing to hit a fly. We’d come prepared with a vast selection of tarpon flies in a range of patterns and colors, but we never had to move beyond the Cockroach: an old classic with a brown bucktail collar over grizzly saddle hackle on a 2/0 hook. With it, we jumped five fish and landed one each before starting our hunt for permit.

Resident to JDR, the tarpon we targeted in February run from 20 to 60 pounds. From April through June, however, the area sees a migration of 100-pound class fish, just like in the Florida Keys. The guides say they hit just as eagerly as the resident fish, and it’s possible to stake out and cast to the giants through an entire tide as they stream by.

Permit Tales

During our pursuit of permit, we fished some spectacular water and also worked down rugged coral shorelines in rough conditions, mere feet from boat damage. In one such place, we rounded a point and spooked a school of tarpon. As they skedaddled past, I fired a long cast with a permit fly across their departing backs, stripped the fly back toward them and hooked up. With the bonefish and tarpon so gullible, you’d suspect that permit would exhibit the same propensity. But even in a nonjaded state, permit are maddeningly contrary.

In a grassy, wind-swept basin, we found five meaty black tails sticking above the chop, just 90 feet away. But no takers. On the oceanside flats, we spotted fish over clean, white sand bottom, 300 yards away. Bemba positioned the skiff perfectly, but when the permit arrived to the point of intersection, we watched them circle the fly on a perfect presentation before moving on.

The Avalon guides pride themselves on their permit fishing, and none more so than Bemba, who’s about as good as they get. He insisted on fishing the Avalon permit fly in standard cream and brown, but he gradually weakened, allowing a couple other color schemes and, finally, the full range of crab patterns we had with us.

It didn’t matter. I kept score: Over five days, we targeted 84 permit; 35 of our casts were spot on, perfect, Bemba said. But none ate the fly. After every cast, we consulted with him. What went wrong? Permit are permit, anywhere in the world.

Bemba said in 17 years of guiding, his clients have taken 50 permit, and those odds are enough to keep him energized. Only once did he flag, and that’s when we suggested casting a live crab, just to land a fish and get some pictures. He became despondent at the suggestion of fishing with anything but a fly. We might as well have disparaged his mother and the Blessed Virgin in one breath.

That’s a Wrap

So went our days in the Gardens: hard work and no payoff on the permit, with regular breaks to catch bonefish and a couple of tarpon, which consistently proved as accommodating as the permit were infuriating.

As a break from the flats fishing, we had our sights set on exploring the reef in hopes of catching big cubera snapper. This is a specialty game. The Italian anglers at the lodge, who had fished for them on past trips, explained that these fish would indeed come up to hit big poppers on the surface, but these bruisers required 100-pound braid, minimum, and you could expect to land only one out of every 10 hooked.

Bemba was less than enthused and explained that cubera required a lot of casting. Besides, outfitted with nothing heavier than 60-pound braid, we were under-gunned. So we settled for an hour of throwing big Orcas and Rapalas on an inshore patch reef, where we easily mixed it up with mutton snapper, yellowtail and barracudas until it was time to turn the skiff for La Tortuga and the long trip back to Havana.

Pioneer

Dry Dock

Floating Village

Making Do

Imagine